Fake news persists in ‘patient zero’ PH: Lies live in too many ways

MANILA, Philippines—Fake news has two dimensions—the “genre” and the “label”—which are both prevalent in the Philippines, the crisis’ “patient zero.”

University of Vienna researchers said fake news leads to two dimensions of political communication—the deliberate creation of disinformation and the weaponization of the term to “delegitimize” the media.

The research work “Fake News as a Two-Dimensional Phenomenon: A Framework and Research Agenda,” written by Jana Egelhofer and Sophie Lecheler, said fake news stands for something that is even “larger than the term itself”.

The researchers stressed that fake news directs a shift in political and public perception of what “journalism and news represent and how facts and information may be obtained in a digitalized world.”

The 2016 elections in the Philippines saw a wave of fake news being unleashed—edited photos, spliced videos, and even replication of legitimate news websites—especially against the rivals of then Davao City local executive Rodrigo Duterte.

Article continues after this advertisementWith a substantial lead against his rivals for the presidency then, he was later heard condemning media for “sensationalism” and for being “biased,” saying that some media firms pretend to be the “moral torch of the country.”

Article continues after this advertisementREAD: Duterte hits media for sensationalism, bias

The Philippines was later considered by Jason Cabañes, a communications professor of the De La Salle University, as patient zero of digital disinformation—fake news on social media.

Cabañes, at the time, told ANC that “disinformation in the Philippines is becoming much more entrenched, diverse and especially profitable for people who are part of it.” He said the problem has become concerning.

Jose Mari Lanuza, Jonathan Ong, and Rose Tapsell, who are all media experts, stressed that concerns were raised that Duterte’s 2016 victory and continued popularity “are outcomes of dark technological alchemy.”

‘Serious problem’

Dr. Imelda Deinla, who heads the watchdog Boses, Opinyon, Siyasat, at Siyensya para sa Pilipinas (BOSES Pilipinas), said while social media democratized access to information, “the downside is that these may be misleading and contain disinformation.”

While there are only 41 percent and 24 percent of Filipinos who access the internet for news about the government and elections, 99 percent access the web for Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, which are social media platforms where false information is pervasive.

The problem, Deinla told INQUIRER.net, is that since the Philippines is already considered patient zero when it comes to risks of an “infodemic,” the weaponization of social media has become highly visible.

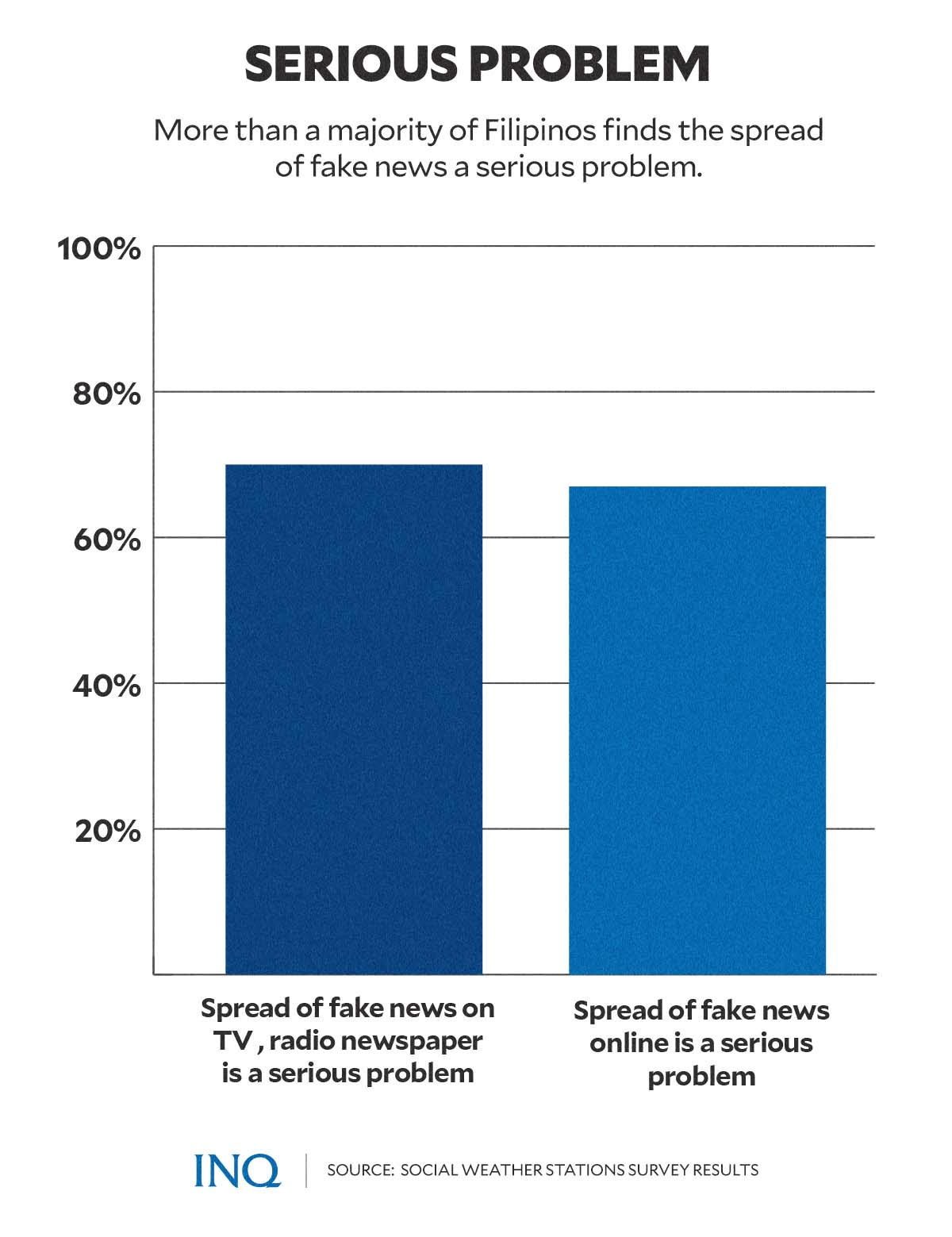

Last Feb. 8, the Social Weather Stations (SWS) said 70 percent of Filipinos consider the spread of fake news on TV, radio and newspaper as a serious problem. At least 67 percent said the spread of fake news online is a serious problem.

READ: The perils of disinformation

It was likewise revealed by the SWS that one out of two Filipinos find it hard to spot fake news on social media and even on traditional media, like TV, radio and newspaper.

There are 38 percent of Filipinos who find it “somewhat difficult” to detect fake news, 13 percent find it “very difficult,” 37 percent find it “somewhat easy,” while 11 percent find it “very easy.” Only 20 percent said they often spot fake news.

Last year, BOSES Pilipinas said “our students only have average skills in identifying fake news.” This was the result of a research work conducted by Ateneo School of Government researchers led by Deinla.

Most—or 52.5 percent of the 20,000 youth respondents—got only six to eight correct answers, or an average score of 6.9, in a 10-item fake news quiz that was held May to June and August to September 2021.

BOSES Pilipinas said the results indicated that respondents who are strongly backing the President are more likely to believe in fake news and are likely to disbelieve real news.

READ: Study: DDS susceptible to fake news

‘Fake news’ hits poor

Danilo Arao, a professor of University of the Philippines Diliman’s College of Mass Communication (UPD–CMC), said internet inaccessibility and lack of media literacy are the reasons fake news has persisted.

He told INQUIRER.net that one of the inadvertent enablers of disinformation would be telecommunications companies because of the limited free data they provide “especially to prepaid users”.

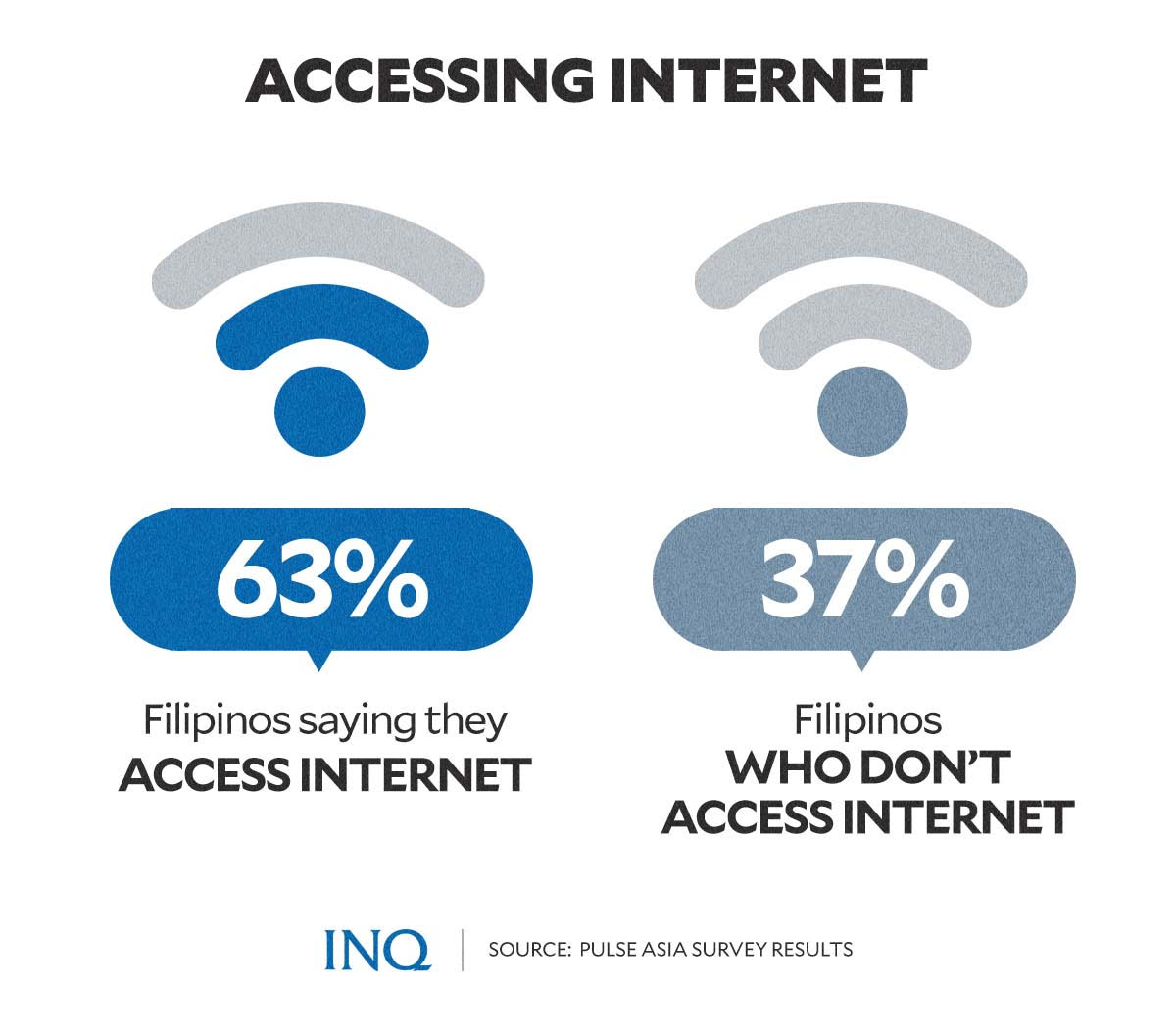

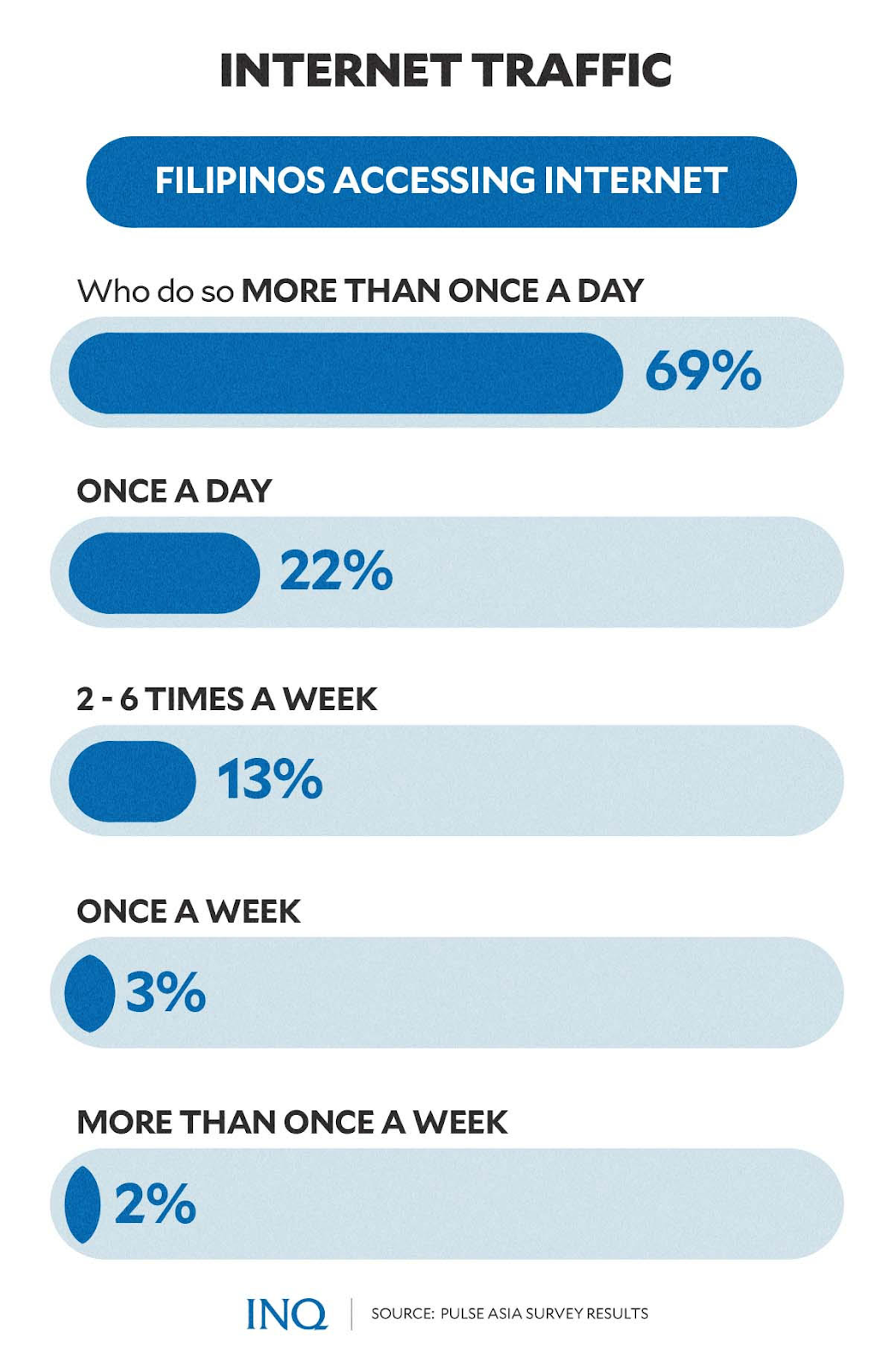

Pulse Asia said last year that 63 percent of Filipinos access the internet while 37 percent don’t. Out of the 63 percent, 69 percent access the web more than once a day.

It said there are 22 percent of Filipinos who access the internet once a day while 13 percent access two to six times a week, three percent access once a week and two percent access more than once a week.

There are 48 percent of Filipinos who consider the internet as a “news source” with Facebook having the lead (44 percent), online news sites (10 percent), other social media sites (seven percent) and Twitter (one percent).

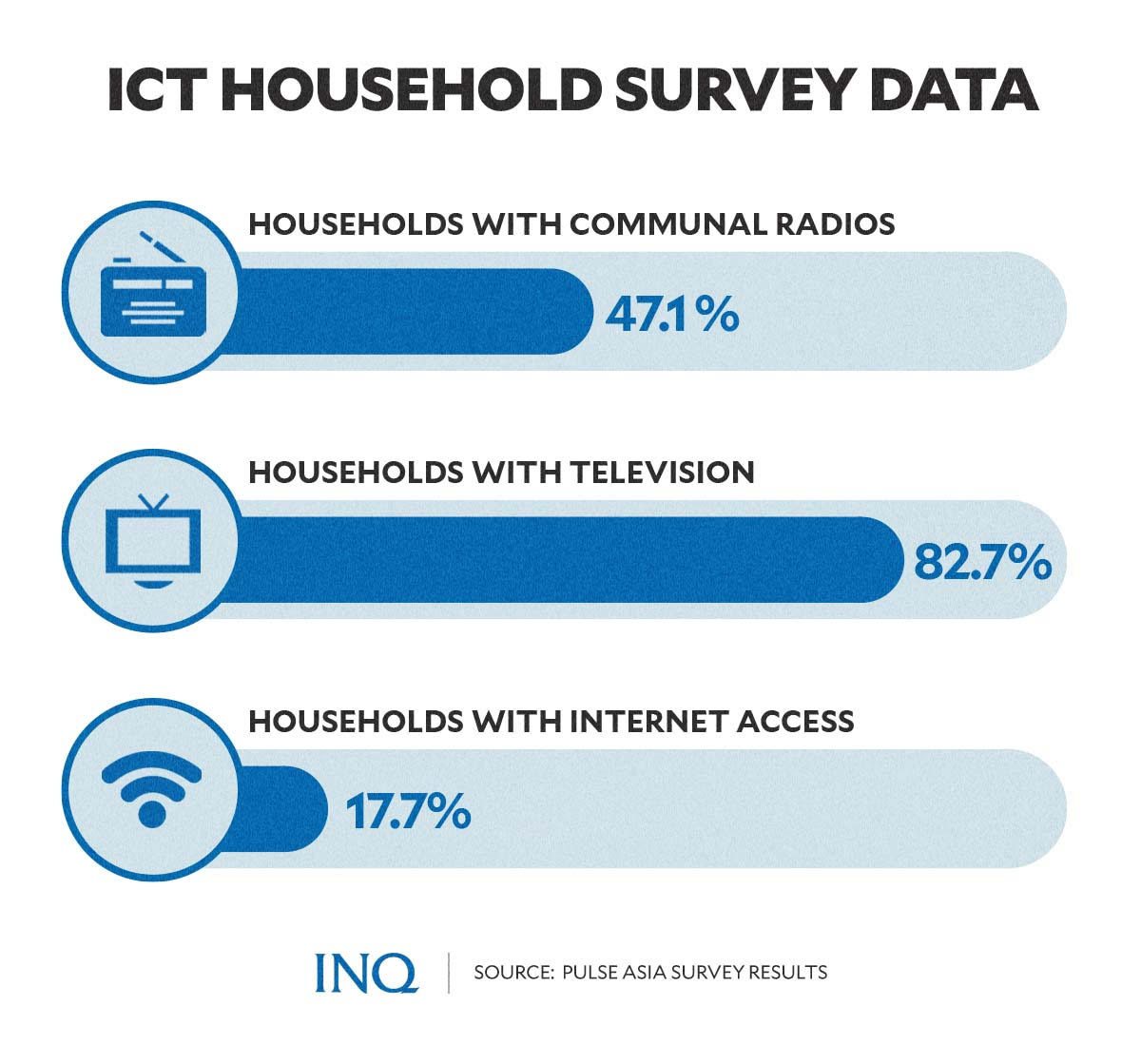

This, as the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) said, only 17.7 percent of Filipino households “have their own internet access at home.”

Arao explained that since these individuals get access to Facebook through limited free data, they would not have enough data to access links or even watch videos from trusted or trustworthy sources.

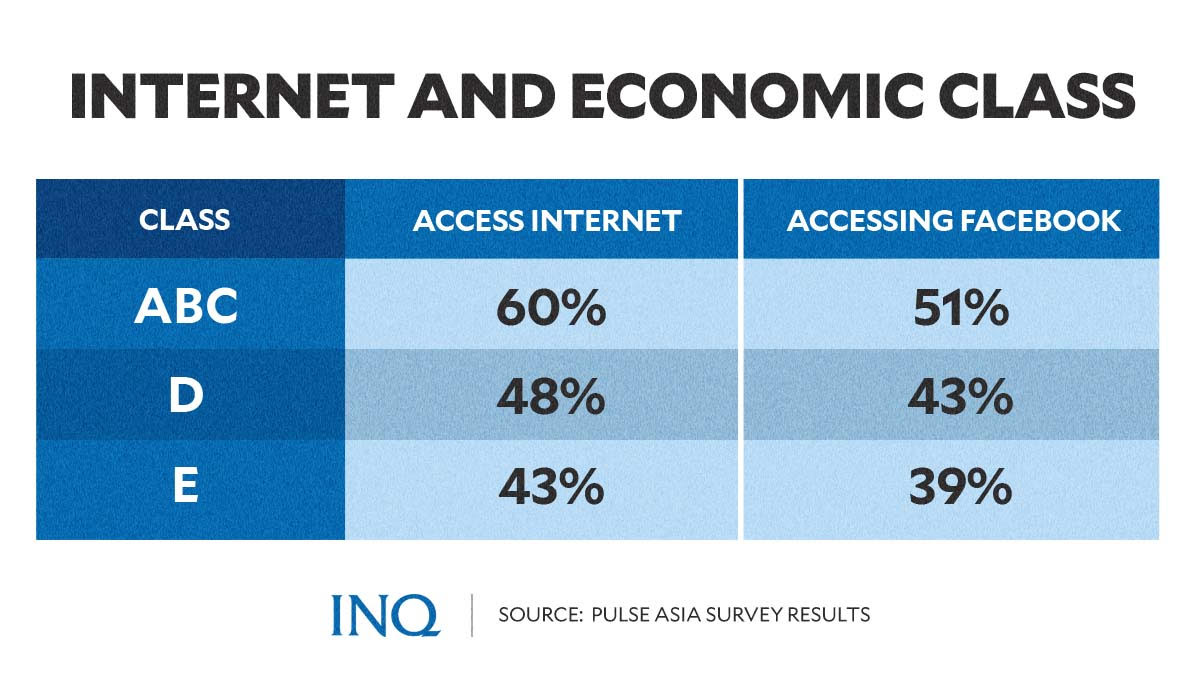

Pulse Asia said out of the 60 percent of Filipinos from classes A, B, and C who access the internet 51 percent access Facebook while out of the 48 percent from class D who access the internet, 43 percent access Facebook.

There are 43 percent of Filipinos from class E who access the internet––out of the 43 percent, 39 percent access Facebook, Pulse Asia said with reference to its research last year.

While free data promos are not really conscious efforts to sow disinformation, he said it works to the advantage of those who spread fake news because when people rely on limited free data, they really don’t have the chance to fact check.

Arao said the lack of media literacy is also a reason fake news has persisted, stressing that it is very telling when people jump to conclusions relying only on titles of reports which are false or misleading.

Deprived of a chance

The DICT said results of the 2019 National ICT Household Survey revealed that 47.1 percent of Filipino households have communal radios while 82.7 percent have TVs.

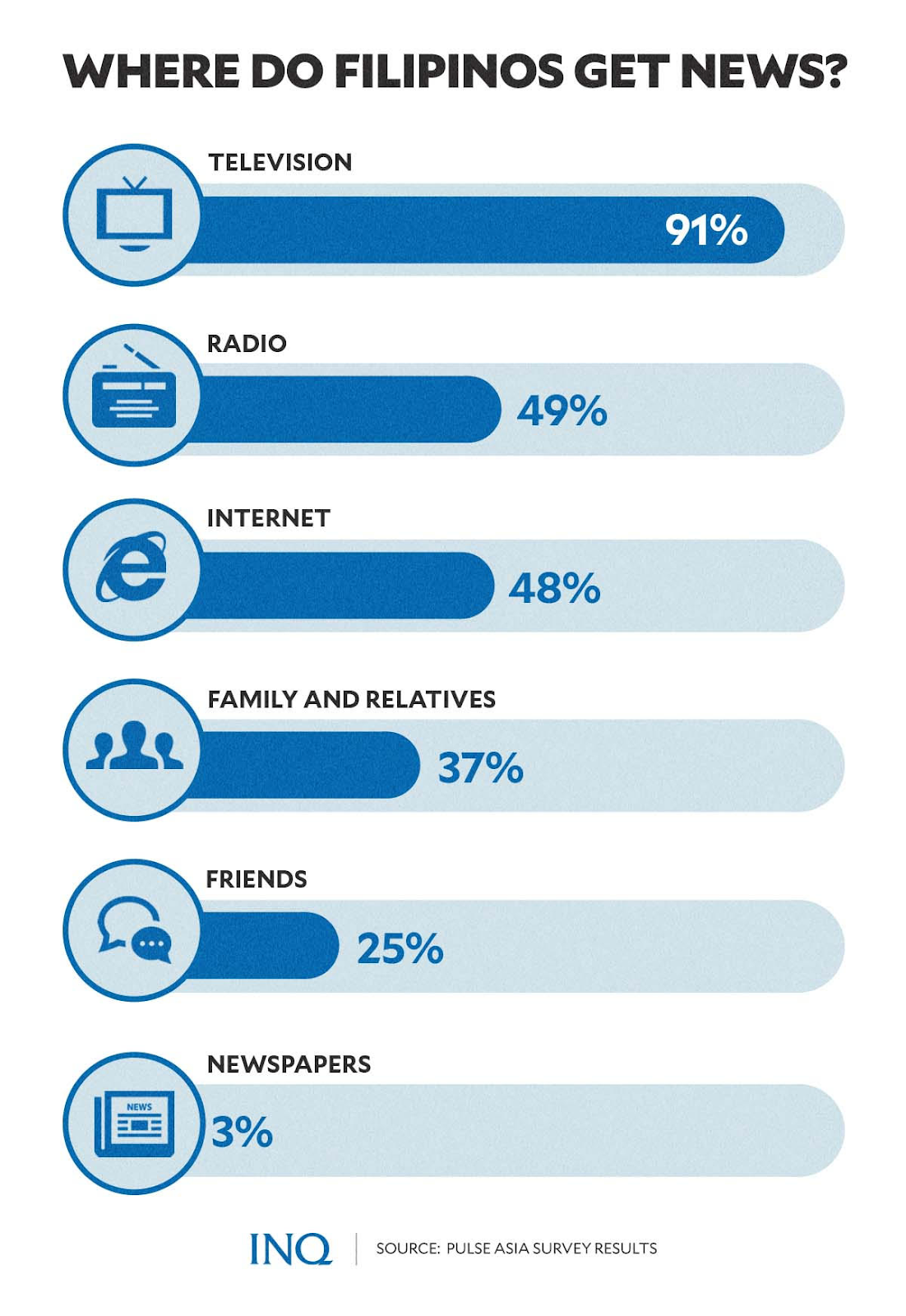

This was possibly the reason why last year, 91 percent and 49 percent of Filipinos considered TV and radio, respectively, as news sources. The internet was third on the list.

Pulse Asia said 82 percent and 25 percent of people get news from national television stations and local television stations while 18 percent and 32 percent get news from national radio stations and local radio stations.

However, when broadcast company ABS-CBN was shut down following Duterte’s rants against it, at least 52 regional TV and radio stations broadcasting in six languages had been closed down.

READ: House panel closes down ABS-CBN

This, as some media outlets, like Apollo Quiboloy’s SMNI, Arao said, became an “enabler of disinformation,” citing the recent presidential debate it hosted where Ferdinand Marcos Jr. was introduced as a master’s degree holder.

Prevalence of ‘fake news’

The study “Fake News: Why Does it Persist and Who’s Sharing It?” revealed that fake news spreads so quickly because of novelty and repeated exposure.

For Deinla, fake news is brief and concise. “That’s a clickbait. That’s what Filipinos would ring into” she said, stressing that fake news contents elicit reader emotions.

“You can elicit emotions in very short, simple messages and the lack of verifiability of contents online is likewise one of the things that make disinformation really part of the lives of many,” she said.

An example, Arao said, would be Banat By, an outright “DDS influencer,” who exaggerates reality when commenting on videos: “It’s an effective way to provide information, it’s like the higher way of infotainment.”

Arao said the use of “DDS influencers” as news anchors, reporters or columnists gave legitimacy to the practice of enhancing political images through fake news.

“It lends legitimacy to their ‘disinformation cause’ because they are already recognized as members of the media and in the process, they are being perceived as ‘truth tellers’ like journalists,” he said.

Arao stressed that he himself fell victim to disinformation by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-Elcac) in the SMNI program “Laban Kasama ang Bayan.”

“I’ve been red-tagged twice by the NTF-ELCAC program, so it’s really like they are tolerating red-tagging. Even the Presidential Communications Operations Office would be enablers by accrediting them as bloggers,” he said.

Tracking disinformation

In 2019, a research was conducted by media experts Ong from the University of Massachusetts, Tapsell from the Australia National University and Nicole Curato from the University of Canberra.

The research paper “Tracking Digital Disinformation in the 2019 Philippine Midterm Elections” revealed that the size of digital black operations varies: Some “teams” consisted of 20 people, others far less.

“The larger the operation, the more diverse and widespread the work,” the researchers said.

They said social media campaigners have varied work arrangements with political candidates: “Many digital campaigners are hired by the candidate to run above-board campaigns and manage their official accounts.”

The black operations campaigners were rarely directly hired by candidates, and sometimes not even directly linked to the central campaign team, they said.

For Arao, when disinformation exists, “keeping an army of trolls and making certain that you have influencers on your side would mean advantage.”

Ong, Tapsell and Curato said “influencers” had been weaponized––these are personalities who cultivate more intimate and interactive relationships with their followers on social media.

They said there was a rise in “influencers” in the 2019 elections, however, they are not high-profile––they are “micro-influencers” who seeded political messages in a much more clever and hard to detect manner.

Lies and the elections

The emergence of the fact-checking initiative Tsek.ph could not have come at a more appropriate time as campaign for the 2022 elections has pushed to the surface many examples of disinformation.

Yvonne Chua, professor of mass communications at UP Diliman, said false or misleading claims are getting full play on social media in favor of or against candidates.

Tsek.ph said since January 2022, it had already consolidated over 200 fact checks. It stressed that “a lot has come out ahead of the May elections based on our initial analysis.”

Chua said most of the false or misleading contents were directed against presidential candidate and current Vice President Leni Robredo: “Every week, she is the biggest victim of disinformation or negative messaging.”

READ: Robredo is biggest disinformation victim; Marcos gains from ‘misleading’ posts — fact-checker

One of the targets of misinformation was Robredo’s online medical consultation program Bayanihan E-Konsulta. One of the claims against the program that had been fact-checked and turned out to be false was that it was designed to collect voter data to help Robredo chart her campaign.

READ: Robredo: Disinformation, fake news still biggest challenge to presidential bid

On Facebook last Jan. 12, former broadcaster Jay Sonza claimed that another Robredo program, Angat Buhay, had been distributing plastic containers—water filters—that had traces of lead, a highly toxic metal.

The UP College of Medicine’s Mu Sigma Phi, which donated the 70 water filters, said that the OVP’s “Project H20 makes use of water filtration buckets that are food-grade and safe for use.”

Deinla, professor and lead researcher of Ateneo School of Government, said candidates were not expected to admit operating troll farms but have the duty to “confirm or deny” content being spread by trolls.

Deinla said some candidates will find fake news to be to their advantage as people cannot quickly distinguish between what’s real and what’s not.

Arao said one of the impacts of the fake news phenomenon was to discredit traditional media as Duterte had repeatedly done in the past by branding some media owners as “biased and oligarchs.”

Arao said people, who seek power, saw the power of social media so hitting traditional media was one of the tactics to shift people’s trust. “We are seeing that effect now.”

Ver Reyes (Ph.D.), a psychologist, said the traditional media should take the chance to reflect on how they can better present news instead of trying to remove the stigma of being “biased.”

Reyes told INQUIRER.net that psychologically, the reasons for the prevalence of disinformation could be “confirmation bias and group polarization.”

She said confirmation bias is one of the reasons people would consume information to strengthen or confirm one’s belief and dismiss those that do not support what they believe in.

Group polarization, she said, is the strengthening of a stand as a consequence of a group discussion, stressing that initially held views become even stronger because of a group discussion.

For Deinla, when one already has a belief, he or she is expected to look for things that already confirm his or her belief: “With this kind of information, then the tendency is to actually put you into that echo chamber.”

“Social media has created this echo chamber for many people and in terms of our research, even the nature of fake news is actually beyond the biases that we have. It’s actually the tendency to perpetuate the confusion,” she said.

The effect, Deinla stressed, is that regardless of the kind of material, one will no longer be able to distinguish between real news and fake news. She said fake news promotes confirmation bias.

Reyes explained that individuals exhibit confirmation bias because psychologically, there is Normative Social Influence and Informational Social Influence.

This, she said, depends on how confident they are in their own independent judgment or how well-informed they perceive the group that is influencing their decisions.

For Deinla, it has been confirmed in their research that fake news actually affects political polarization, saying groups involved in this dynamics will no longer seek credible information and would spread that to their families, neighbors and friends.

Pulse Asia said 37 percent of Filipinos consider their family and relatives as “news sources” while 25 percent consider friends as their news sources. Only three percent are considering newspapers.

Reyes stressed that “people are hit by disinformation because of the failure to educate our citizens—educated in terms of history and in filtering out what is factual from anecdotal, and not simply access to the internet.”

Seed of lies

Ong, Tapsell and Curato said what “micro-influencers” lack in broader reach, they gain in “manoeuverability” and “contrived authenticity” which they said give an impression of raw aesthetic, spontaneity and therefore relatability.

“This makes it easier for them to infiltrate organic communities and evade public monitoring. We list below three sets of disinformation innovations in micro-media manipulation,” they said.

- Micro– and Nano–influencers

The researchers said the “authentic” elation of the “micro-influencers” for a political cause has become an inspirational model for their followers’ own political performance.

- Political parody accounts: These are accounts which take the persona of politicians, government offices or news pages that “pokes fun” at the mistakes and excesses of their “targets”. Visible on Facebook and Twitter, they employ emotionally-enticing and occasionally-vulgar language.

- Pop culture accounts: These are accounts of fictional pop culture figures that comment on Filipino society in general. Present on Facebook and Twitter, they talk about political propaganda and hashtags in between inspirational quotes, or fun posts.

- Thirst Trap Instagrammers: These are accounts of hyper-sexual Instagram users displaying their bodies for likes and followers. They post political content in between “flirtatious poses and lifestyle posts.”

- Alternative News

In 2019, Ong, Tapsell and Curato said “alternative news” which was seen rising, especially with impostor news websites that impersonate real media institutions, was diverse.

- Hyper-partisan news channels: These are news Facebook pages or Youtube channels that have “explicit political alignments catering to political fandoms” and employ emotions of anger and resentment.

- Thematic/Local News: These are platforms that consolidate news for specific topics and localities. Visible on Facebook, these are “neutral-sounding while occasionally sneaking in political propaganda”.

- Closed groups

The researchers said these are organic communities based on common interests, but are at risk from infiltration by political operators, stressing that “tactics here can either be explicitly political and hyper-partisan or discreetly seeding paid political propaganda.”

- OFW Closed Groups: These private groups vary in size and scale while catering to overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) in certain countries or small towns, discussing a range of social issues.

- Conspiracy Closed Groups: These private groups become “cesspools of scientific and political falsehoods, and occasionally seed election–related propaganda. These contain conspiracies while seeding content with a clear political slant.