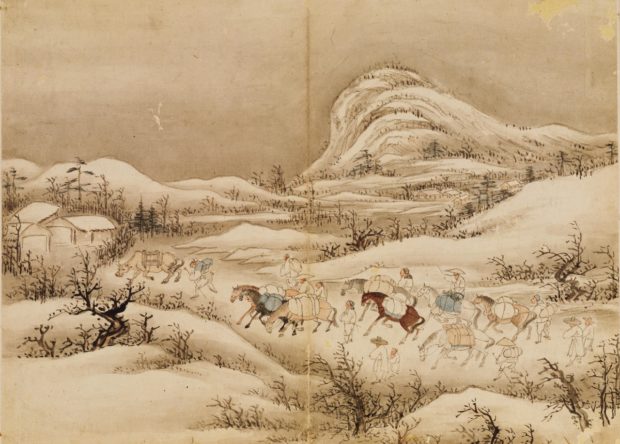

How Koreans survived winter the old-fashioned way

SEOUL — The winters in Korea can be notoriously tough with temperatures sometimes falling to below minus 10 degrees Celsius.

Seoul saw the coldest day in 35 years in January last year, with a low of minus 18.6 degrees Celsius. Some parts of the city such as Nowon-gu and Eunpyeong-gu registered lows of minus 21.7 and 22.6 degrees Celsius respectively, according to the Korea Meteorological Administration.

Records also show that winter used to be longer on the Korean Peninsula. The average yearly temperature of the last three decades between 1991 and 2020 rose by 1.6 degrees, compared to between 1912 and 1940, according to data from the weather agency.

So how did previous generations, without central heating and electric heaters, survive these long cold winters?

“When Korea was a traditionally agricultural society in the past, people did not move around all day long like we do now. During the winter, people relied on the food and work they had done during the other seasons, and spent a lot of time at home and in the village,” said curator Lee Gwan-ho from the National Folk Museum of Korea.

Article continues after this advertisement

A furnace for room heating and cooking at the house of the late Shin Jae-hyo in Gochang (Cultural Heritage Administration via The Korea Herald/Asia News Network)

Born in Hongseong County, South Chungcheong Province, in the 1960s, he recalls living through many long cold winters.

Article continues after this advertisement“Hanok (traditional Korean houses) were cold and especially vulnerable to cold breezes coming from the outside. What people did to offset the cold was to burn wood in the agungi (Korean furnaces) to keep the ondol (underfloor heating) warm.”

As trees were hard to come by, people sometimes had to resort to boiling water in a gamasot, a big pot used in Korean cooking.

“Through its modern history following the Korean War when the country was economically struggling, the heating system in many homes was not as modern as it is now. It resembled the traditional system much more, especially in the countryside,” he said.

Ondol: Korea’s traditional floor heating system

Ondol may not be a Korean invention, but it has been an integral part of the Korean lifestyle since the Joseon Dynasty, which began in 1392. As early 20th-century historian Son Jin-tae famously said, “Koreans were those who were born, raised and died on ondol.”

Isabella Bird Bishop, a 19th-century British writer who extensively traveled through Korea, once said it was too hot to sleep during her stay at an inn.

In her book “Korea and her Neighbours” published in 1898, she wrote, “The room was always overheated from the ponies‘ fire. From 80° to 85° was the usual temperature, but it was frequently over 92°.”

“I spent one terrible night sitting at my door because it was 105° within. In this furnace, which heats the floor and the spine comfortably, the Korean wayfarer revels.”

The modern floor heating system installed in almost all Korean homes now has its roots in this old-fashioned ondol using a wood-burning furnace, explains professor Kim June-bong, president of the International Society of Ondol.

“(Today’s) water-based underfloor heating system which works with warm water that circulates through pipes connected to a boiler is an improvement from the same mechanism where an agungi used to warm up the floor in traditional Korean houses,” he said.

“The heating system used in apartment buildings is essentially ondol.”

Unlike radiators which come from the West and are intended to keep the air warm, ondol warms the floor, Kim said. It is more pleasant, thrifty, and keeps your feet warm.

Nubi: Quilting with a spiritual influence

Nubi, a quilting technique in Korea, was also used to keep people warm. The traditional quilting involves sewing materials such as cotton wool into clothes and fabric.

“With no such thing as ‘insulated clothes’ at that time, nubi was used to help protect from cold weather,” said Kim Hae-ja, who earned the title of Master Artisan of Quilt from the Cultural Heritage Administration.

She noted that nubi became more common after cotton was introduced in the country thanks to Mun Ik-jeom, a politician of the Goryeo Kingdom. However, the technique had already existed before then.

“Among the upper class, seamstresses did the job, while commoners did not have time to quilt their clothes. They were too busy,” Kim Jae-ha said.

Quilted trousers of the Kim clan in Cheongju (Cultural Heritage Administration via The Korea Herald/Asia News Network)

Records show that clothes padded with cotton were made and sometimes paid to the government as a form of tax, she explained.

Though quilting itself is not unique to Korea, the level of dedication and the extent to which nubi covered a piece of clothing were, in order to give the clothes a religious meaning.

“As if a subject of religious belief, people used to believe that putting effort into clothes would bring luck and avoid difficulties. Nubi, in my view, is a product of dedication,” she said.

It is worth noting however that nubi was not common, she added. It was often reserved for people of high class, including bureaucrats and public servants as well as army soldiers during the Joseon Dynasty.