MANILA, Philippines—“Real and not contrived.”

The human rights group Karapatan (Right) used those words to describe the threat to life that confronts individuals who had been red-tagged, or accused of being communist rebels or sympathizers.

The words rang loud when Dr. Mary Rose Sancelan, who heads the rural health unit of Guihulngan City in Negros Oriental province, was murdered after she was red-tagged.

Red-tagging, said Karapatan, has “serious implications.”

READ: Red-tagging: It’s like ‘living with a target on your head’

Sancelan was killed over a year since she was tagged by the anti-communist vigilante group Kawsa Guihulnganon Batok Kumunista (Kagubak) as the alleged New People’s Army (NPA) spokesperson by the pseudonym of JB Regalado. Her name was seen on the vigilante group’s “hit list”.

Red-tagging has been defined by Senate Bill No. 2121 as the act of labeling, vilifying, branding, naming, harassing, persecuting individuals and groups as “state enemies, left-leaning, subversives, communists, or terrorists.”

Karapatan, however, said that red-tagging is akin to a death warrant that brings grave risks to those who had been branded. Often, hit lists become kill orders, especially following President Rodrigo Duterte’s instructions to police and military to “kill them all” referring to communist insurgents.

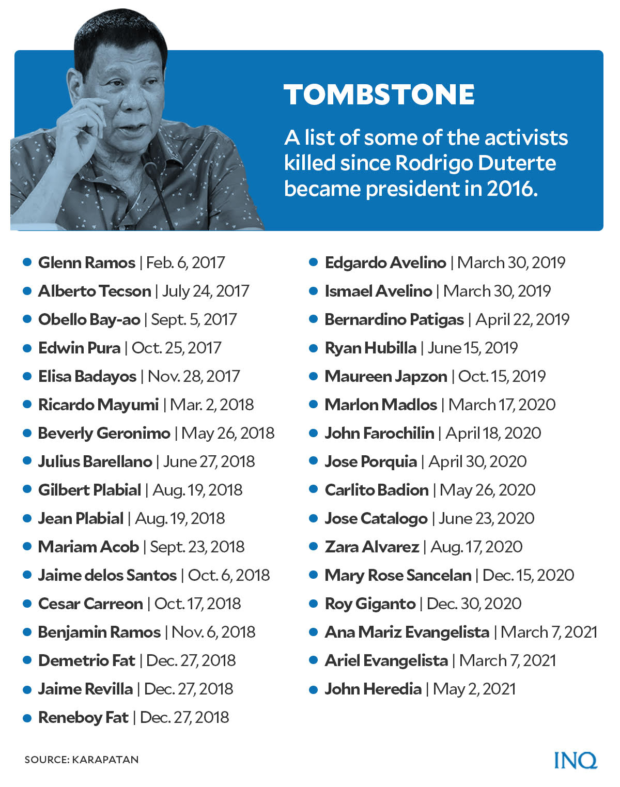

Sancelan, who was killed with her husband on Dec. 15, 2020, was one of the 421 activist deaths documented by Karapatan since July 1, 2016—Duterte’s first day in Malacañang.

The killing of Sancelan, Karapatan said, showed “how relentless vilification leads to merciless death.” Karapatan told INQUIRER.net that in over five years, 33 red-tagged activists had been killed:

• Glenn Ramos

Ramos, the former coordinator of Bayan Muna in Davao City, was killed on Feb. 6, 2017. The military said he was an NPA official, but his family said he was a construction worker. The military said Ramos had a warrant.

• Alberto Tecson

Tecson, who was killed on July 24, 2017, was the vice chair of the fisherman’s group Pamalakaya in Guihulngan City. A day before his killing, the military was looking for him, alleging that he was transporting rebels. The military said it was not behind his killing, though.

• Obello Bay-ao

Bay-ao was with the Liga ng mga Iskolar ng Bayan when he was killed on Sept. 5, 2017 in Talaingod, Davao del Norte by alleged militia men. A lumad himself, Bay-ao was one of the countless indigenous people who had been tagged as communist rebels.

• Atty. Benjamin Ramos

Ramos, who was part of the National Union of People’s Lawyers, was killed in Kabankalan City, Negros Occidental on Nov. 6, 2018. Karapatan said he had been “labelled as a communist” early in 2018.

• Bernardino Patigas

Patigas, an official of the North Negros Alliance of Human Rights, was killed on April 22, 2019. Before his killing, he was accused of being a rebel and his photo was seen on a hit list allegedly posted by the police in Moises Padilla town.

READ: Bishop calls slain Escalante councilor a ‘martyr,’ seeks end to killings

• Zara Alvarez

Alvarez was a paralegal of Karapatan in Bacolod City, Negros Occidental when she was killed on Aug. 17, 2020. Her photo was also seen on the hit list that also carried the photos of Patigas and Ramos.

READ: Slain activist was monitoring Negros abuses, killings

Here’s a list of the rest of the victims:

• Edwin Pura, killed on Oct. 25, 2017

• Elisa Badayos, killed on Nov. 28, 2017

• Ricardo Mayumi, killed on Mar. 2, 2018

• Beverly Geronimo, killed on May 26, 2018

• Julius Barellano, killed on June 27, 2018

• Gilbert Plabial, killed on Aug. 19, 2018

• Jean Plabial, killed on Aug. 19, 2018

• Mariam Acob, killed on Sept. 23, 2018

• Jaime delos Santos, killed on Oct. 6, 2018

• Cesar Carreon, killed on Oct. 17, 2018

• Demetrio Fat, killed on Dec. 27, 2018

• Jaime Revilla, killed on Dec. 27, 2018

• Reneboy Fat, killed on Dec. 27, 2018

• Edgardo Avelino, killed on March 30, 2019

• Ismael Avelino, killed on March 30, 2019

• Ryan Hubilla, killed on June 15, 2019

• Maureen Japzon, killed on Oct. 15, 2019

• Marlon Madlos, killed on March 17, 2020

• John Farochilin, killed on April 18, 2020

• Jose Porquia, killed on April 30, 2020

• Carlito Badion, killed on May 26, 2020

• Jose Catalogo, killed on June 23, 2020

• Roy Giganto, killed on Dec. 30, 2020

• Ana Mariz Evangelista, killed on March 7, 2021

• Ariel Evangelista, killed on March 7, 2021

• John Heredia, killed on May 2, 2021

Lives lost

Like Sancelan who had been offering services in Guihulngan City, the rest of the murdered activists had been living in communities of the underprivileged and the poor. Their deaths had been considered “severe losses” by the communities they had been serving.

Badayos lived a life fighting for farmers’ rights. She was killed while leading a mission to investigate alleged land rights violations in Bayawan, Negros Oriental. She was with farmer leader Eleuterio Moises who was also killed.

Jimmylisa Badayos, one of the victim’s children, told INQUIRER.net that Badayos “was defenseless when she was killed because the only thing she had was her commitment to serve Filipinos oppressed by the government.”

Ramos, a lawyer, represented imprisoned activists, including University of the Philippines’ Myles Albasin. He also dedicated his life fighting for the rights of peasants, establishing the Paghiliusa Development Group.

READ: Farmers’ lawyer living simple life – till he was shot dead

Karapatan said that since July 1, 2016, the 33 activists who were red-tagged and killed were peasants (14), rights workers (6), urban poor (3), drivers (2), cultural workers (2), environmentalists (2), health worker (1), journalist (1), youth (1), and lawyer (1).

Most of the 33 activists were from Central Visayas (10), Western Visayas (9), Davao Region (4), Bicol (2), Eastern Visayas (2), Calabarzon (2), Cordillera Administrative Region (1), Caraga Region (1), Central Luzon (1), and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (1).

Rise in deaths

In the last five years, the country has seen a rise in killings under the Duterte administration following the President’s public comments about being ready to be imprisoned if he was charged with the killings of activists.

Karapatan said that in 2016, within the President’s first six months in Malacañang, 19 activists had been killed. In the following years, the count of victims spiked – 2017 (107), 2018 (96), 2019 (71), 2020 (83), and the first eight months of 2021 (45).

In 2020, The Interpreter’s Nick Aspinwall said that the killing of activists signals the “turning point” in the government’s bid to eliminate dissent, saying that the attacks were more closely linked to the military’s counterinsurgency campaign.

The United Nations (UN), last March, condemned the “Bloody Sunday” killing of nine activists in the midst of raids by the military and police in the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas and Rizal.

Truth-tagging?

In May, as the Supreme Court held oral arguments on petitions against the highly controversial Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020, Associate Justice Amy Lazaro-Javier asked about the relentless red-tagging of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict.

Associate Justice Ricardo Rosario likewise raised concern. Assistant Solicitor General Marissa Galandines said the government does not like to use the term since it was “not coined by the government.”

READ: ‘Red-tagging at its finest’

“If I may say this your honor, the term red-tagging was used by the leftists […] It is the submission of the government that what it does is truth-tagging and not red-tagging, your honor,” she said.

In June, the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights recognized incidents of red-tagging in the Philippines, saying that it was the act of labelling individuals and groups as communists or terrorists.

TSB