Poland passes legislation allowing migrant pushbacks at border

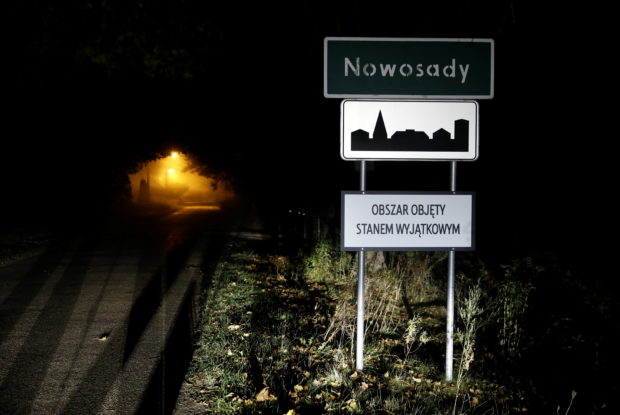

Road sign with “Area covered by a state of emergency” is seen near the Belarusian-Polish border in Nowosady, Poland October 12, 2021. The picture was taken on October 12, 2021. REUTERS/Kacper Pempel

WARSAW — Poland’s parliament passed legislation on Thursday that human rights advocates say aims to legalize pushbacks of migrants across its borders in breach of the country’s commitments under international law.

Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia have reported sharp increases in migrants from countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq trying to cross their frontiers from Belarus, in what Warsaw and Brussels say is a form of hybrid warfare designed to put pressure on the EU over sanctions it imposed on Minsk.

Rights groups have criticized Poland’s nationalist government over its treatment of migrants at the border, with accusations of multiple illegal pushbacks. Six people have been found dead near the border since the surge of migrants.

Border guards argue they are acting in accordance with government regulations amended in August and now written into law. The legislation must now be signed by President Andrzej Duda, an ally of the ruling nationalists, to take force.

The amendments include a procedure whereby a person caught illegally crossing the border can be ordered to leave Polish territory based on a decision by the local Border Guard chief.

Article continues after this advertisementThe order may be appealed to the commander of the Border Guard, but this does not suspend its execution.

Article continues after this advertisementAdditionally, the bill allows the chief of the Office of Foreigners to disregard an application for international protection by a foreigner immediately caught after illegally crossing the border.

Under international law, migrants have a right to claim asylum and it is forbidden to send potential asylum-seekers back to where their lives or well-being might be in danger.

The EU’s home affairs commissioner has said EU countries need to protect the bloc’s external borders, but that they also have to uphold the rule of law and fundamental rights.

Critics such as Poland’s Human Rights Ombudsman and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s (OSCE) Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights say the new law does not guarantee effective recourse for people – migrants or refugees – seeking international protection.

“If there are people who have a legitimate request to seek asylum, there should be a way to allow that to happen,” ODIHR director Matteo Mecacci told Reuters.

“I understand there are also security concerns…but security concerns cannot completely overrun the need for international protection.”