WB tells PH: Pay attention to ‘silent pandemic’ of child stunting

MANILA, Philippines—The Philippines should pour more funds in programs to combat the “silent pandemic” of undernutrition among the poor, the World Bank said on Monday (June 14).

Undernutrition impedes the Philippines’ human and economic development, said Ndiamé Diop, World Bank country director for Brunei, Malaysia and Philippines.

A study released by the World Bank on Monday said that childhood stunting–caused by prolonged nutritional deficiency among infants and young children– is one of the most serious but least-addressed problems in the world and an even more urgent concern in the Philippines.

The Philippines ranks fifth among with other countries in the East Asia and Pacific region in terms of stunting prevalence and is also among the 10 countries in the world with the highest number of stunted children.

Data showed in 2019 that one in three, or 29 percent, of children younger than five years old suffered from stunting. At least 19 percent was also found underweight for their age, and 6 percent of the children with ages below five years old was considered “wasted”, since their weight does not match their height, the World Bank said.

Article continues after this advertisementThe report, titled “Undernutrition in the Philippines: Scale, Scope and Opportunities for Nutrition Policy and Programming,” also said that for almost 30 years, no significant improvement has been found in terms of eradicating undernutrition in the Philippines.

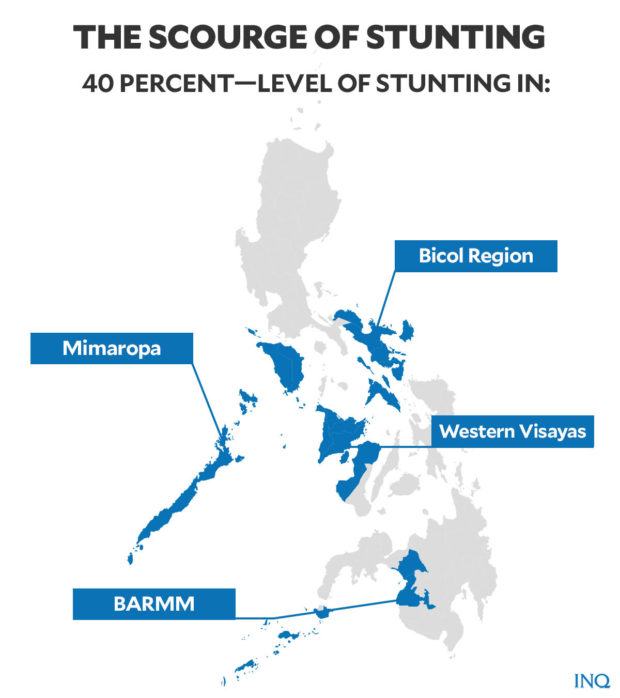

Article continues after this advertisementThe level of stunting exceeds 40 percent of children under five years of age in Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), Mimaropa, Bicol and Western Visayas. In rural areas, children are more likely to be stunted than their urban counterparts, the World Bank said.

Some of key causes of undernutrition are poor infant and young child feeding practices, ill health, low access to diverse, nutritious foods, inadequate access to health services, unhealthy household environment, and poverty.

Diop said undernourished children tend to be sickly, learn less, more likely to drop out of school and their economic productivity as adults can be clipped by more 10 percent in their lifetime, while healthy children can do well in school and look forward to a prosperous future and productive members of society.

“Improving the nutrition of all children is key to the country’s goals of investing in people and boosting human capital for a more inclusive pattern of economic growth,” said Diop.

Nkosinathi Mbuya, World Bank senior nutrition specialist in East Asia and the Pacific region and lead author of the report, said there was a “narrow window” of opportunity for a child to receive sufficient nutrition since a child has only 1,000 days from birth until his second birthday to get enough nutrition.

“Any undernutrition occurring during this period can lead to extensive and largely irreversible damage to physical growth, brain development, and, more broadly, human capital formation,” said Mbuya.

“Therefore, interventions to improve nutritional outcomes must focus on this age group and women of child-bearing age,” he added.

To address the problem, the report strongly recommended that the government must be persistent and challenge the “silent pandemic” by implementing programs to achieve nutrition goals and ensure that these will always be part of the agendas of both the legislative and executive bodies.

SOFIA VERTUCIO, trainee

RELATED STORIES:

Pandemic weakens food security in urban poor communities

Food security in PH: A task for everyone

TSB