Food security in PH: A task for everyone

Farmers, food processors, traders and consumers continue to face food security problems.

A summit to achieve common food security framework is deemed necessary. A consensus may not be achieved initially but a summit could bring stakeholders to a better understanding of the situation from different perspectives.

We need to engage in dialogue in action, one that would involve the participation of many stakeholders and the honest examination of outcomes of policies. This effort may not conclude in one administration but may have to be continued by the next.

We should advance the conversation as far as we can but realize that there may be issues that need to be resolved in the future.

This brief paper will cover four points:

- The present food insecure situation

- A common understanding of food security

- Questions about the food security framework

- Immediate steps to shore up food security

Hunger and food insecurity

Article continues after this advertisementPeople are hungry. Lack of access to food among poor Filipinos is on stark display every day by the long lines to community pantries.

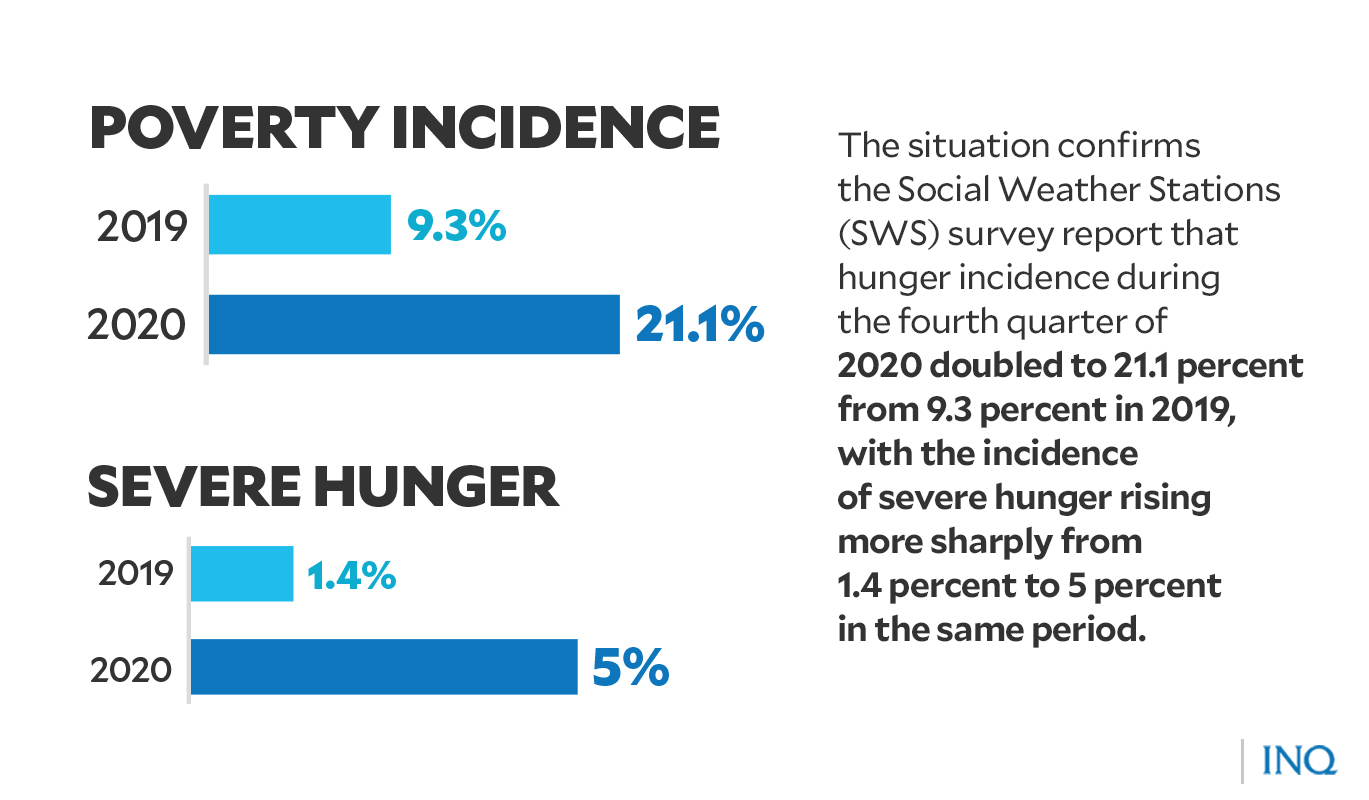

Article continues after this advertisementThe situation confirms the Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey report that hunger incidence during the fourth quarter of 2020 doubled to 21.1 percent from 9.3 percent in 2019, with the incidence of severe hunger rising more sharply from 1.4 percent to 5 percent in the same period.

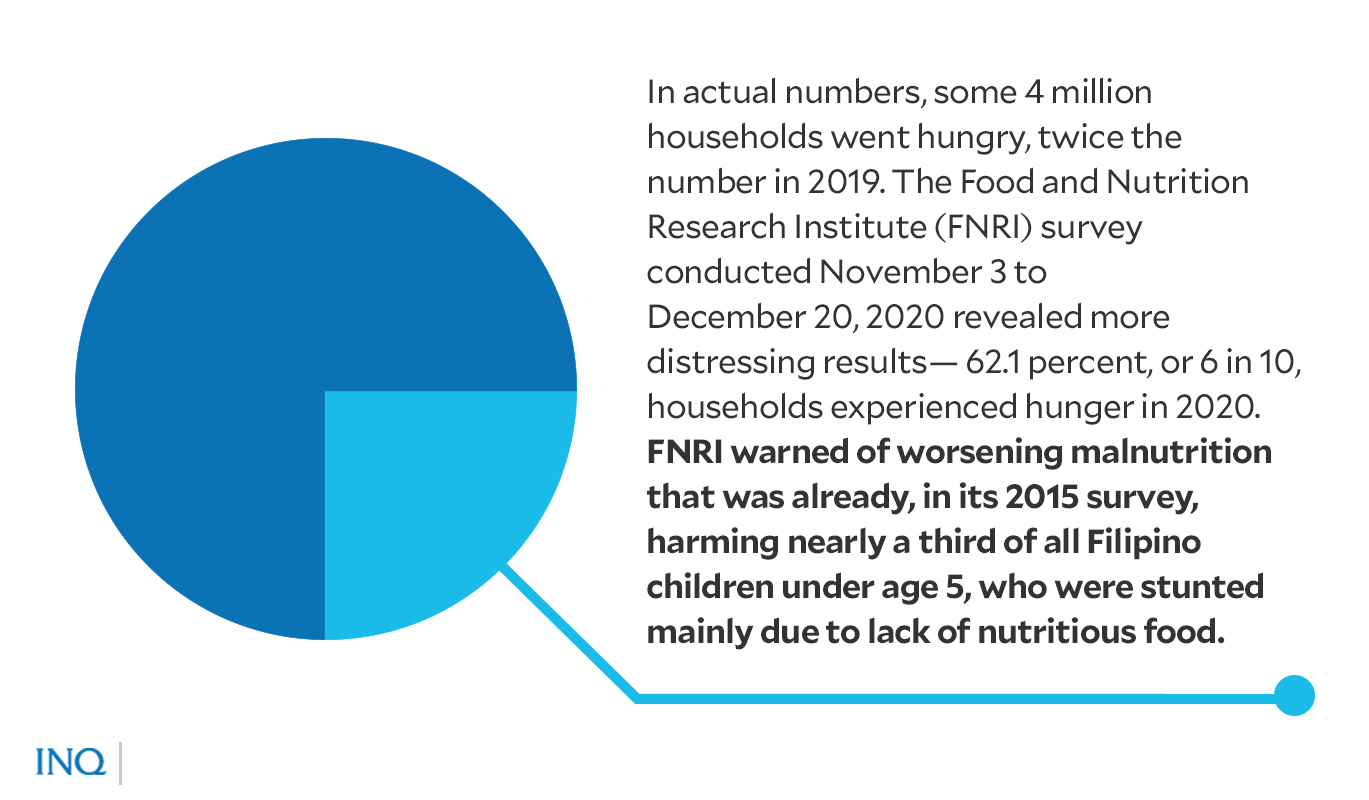

In actual numbers, some 4 million households went hungry, twice the number in 2019.

The Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) survey conducted Nov. 3 to Dec. 20, 2020 revealed more distressing results— 62.1 percent, or 6 in 10, households experienced hunger in 2020. FNRI warned of worsening malnutrition that was already, in its 2015 survey, harming nearly a third of all Filipino children under age 5, who were stunted mainly due to lack of nutritious food.

Low-priced National Food Authority rice (P2 per kg and P32 per kg) has disappeared from the market. The price of the most inexpensive commercial rice has risen. Consumers now pay more for the food staple.

While the hunger situation is undeniable, the responses have ranged from genuine bayanihan giving to condemnation. However, a number of commendable initiatives from the government and the public have been taken, like:

- Farm produce purchased directly from farmers and distributed through community pantries benefited producers and consumers alike

- Backyard and community food production has been enhanced

- Middle-income consumers have been more open to paying a premium for local produce.

Palay farmers are suffering due to low prices. Prices at some point in the last two years have dipped to below the average cost of production of P12 per kg.

Some rice millers have become importers, as trading margins have become more attractive than processing palay into rice. Not all traders have benefitted from the present system as some complain that they, too, have seen their profits dwindle.

Toward a Common Understanding of Food Security

In his initial draft framework paper, “Towards a Common Understanding of Food Security,” Dr. Cielito Habito, former director general of the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda), cited the formal definition of food security by the World Food Summit (WFS) and the assessment tool developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU):

The globally accepted formal definition was adopted in 1996 at the World Food Summit spearheaded by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN-FAO): “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

Elaborating on this definition, FAO identified four dimensions:

- Food availability is the availability of sufficient quantities of food of appropriate quality, sourced from either domestic production or importation (including food aid).

- Food access is individuals’ ability to acquire appropriate food for a nutritious diet. Critical here is the price of food, alongside individual and family incomes. Access is conditioned by the legal, political, economic and social arrangements of the community in which they live.

- Utilization is adequate diets, clean water, sanitation and health care to reach a state of nutritional wellbeing where all physiological needs are met. This points to the importance of non-food elements in food security.

- Stability implies that a population, household or individual must have access to adequate food at all times to be food secure. They should not risk losing access to food as a consequence of sudden shocks, like economic or climate crisis or cyclical events.

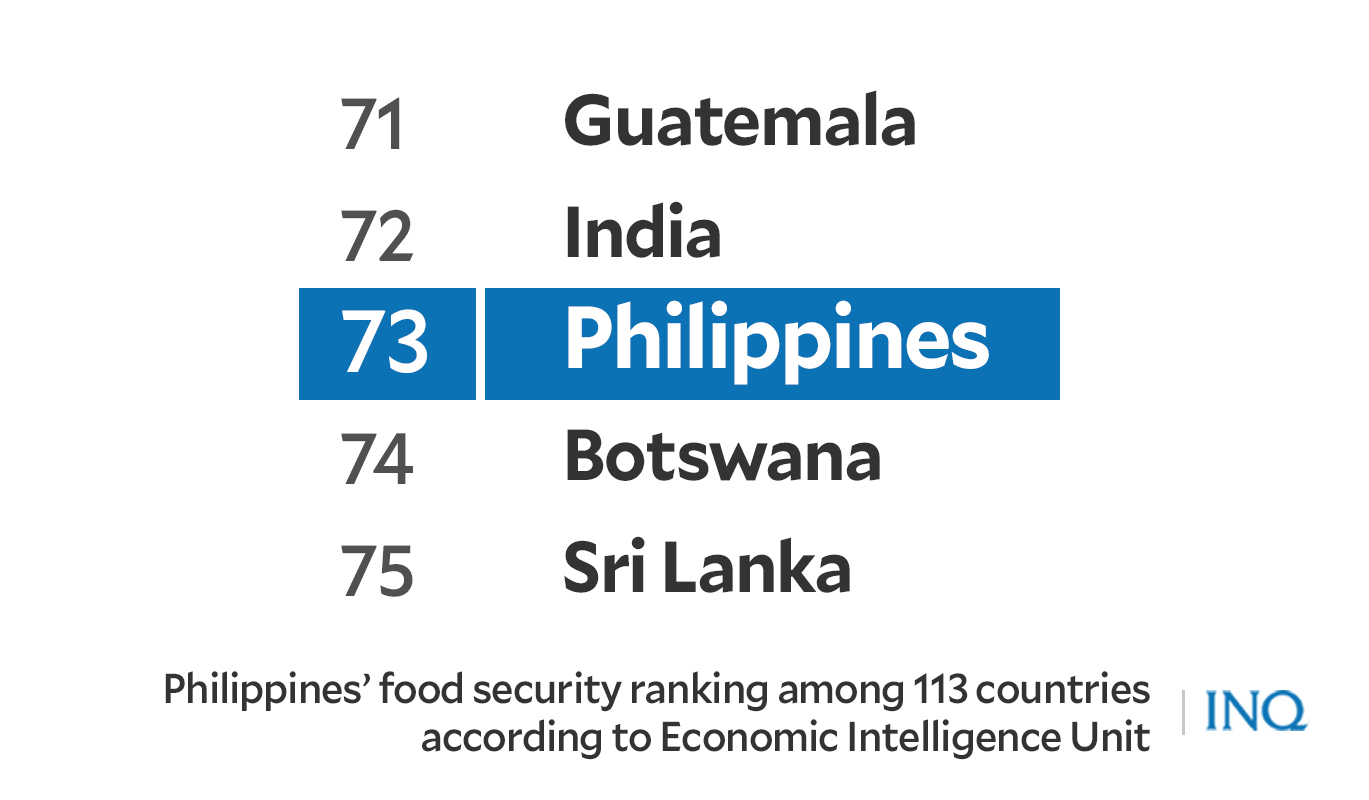

To provide an assessment tool, EIU has been publishing the Global Food Security Index covering 113 countries since 2012. Countries are rated annually based on 59 unique indicators measuring the drivers of food security across both developing and developed countries (EIU 2021).

The index was defined in the three categories of Affordability, Availability and Quality & Safety, with a fourth category on Natural Resources and Resilience added in the 2020 edition. Broadly similar to the FAO characterization, these dimensions are elaborated as:

- Affordability—Measures the ability of consumers to purchase food, their vulnerability to price shocks and the presence of programs and policies to support customers when shocks occur

- Availability—Measures the sufficiency of national food supply, the risk of supply disruption, national capacity to distribute food and research efforts to expand agricultural output

- Quality and Safety—Measures the variety and nutritional quality of average diets, as well as the safety of food

- Natural Resources and Resilience—Assesses a country’s exposure to the impacts of climate change, its susceptibility to natural resource risks and how the country is adapting to these risks.

Finland, Ireland and the Netherlands are the top three on food security. The lowest three are Zambia, Sudan and Yemen. The Philippines is 73rd just above Botswana, Sri Lanka and Nicaragua and trailing Myanmar, Guatemala and India.

Two Philippine laws carried provisions on food security and sufficiency. These are official definitions and declarations that cannot be ignored.

The Republic Act No. 8435, or the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act (AFMA), defined food security as:

“Food Security’ refers to the policy objective, plan and strategy of meeting the food requirements of the present and future generations of Filipinos in substantial quantity, ensuring the availability and affordability of food to all, either through local production, or importation, or both based on the country’s existing and potential resources endowment and related production advantages and consistent with the overall national development objectives and policies. However, sufficiency in rice and white corn should be pursued.”

In its declaration of policy, AFMA said:

“The State shall promote food security, including sufficiency in our staple food namely rice and white corn. The production of rice and white corn shall be optimized to meet our local consumption and shall be given adequate support by the State.

Another law, Republic Act 11321, or the Sagip Saka Act, stressed the importance of fair returns and a decent living for farmers and fishers as the sustainable way to food security. The law’s declaration of policy states:

“It is the declared policy of the State to achieve sustainable modern agriculture and food security by helping the agricultural and fishing communities to reach their full potential, increasing farmers’ and fishermen’s incomes, and bridging gaps through public-private partnerships, thereby improving their quality of life

“In pursuance of this policy, the State shall strengthen the farmers and fisherfolk enterprise development program by establishing a comprehensive and holistic approach in the formulation, coordination and implementation of enterprise development initiatives, consolidating the roles of different agencies involved in farmers and fisherfolk enterprise development, and intensifying the building of entrepreneurship cultures among farmer and fisherfolk.”

It is clear from these provisions that it is important that both food security and food sufficiency be accepted as guiding principles not to be pitted against each other. Food security is the larger objective but on food staples, sufficiency is to be sought. No timetable is given. It is up to the Executive Branch to work this out.

It is practical, however, to accept three caveats:

- Imports should not be banned, as these may be needed when there are shortfalls and some competition can be helpful. Excessive imports, however, depress prices unduly, causing farmer poverty and discouraging local production. The AFMA indicated openness to importation while in pursuit of sufficiency. Sagip Saka underlines the importance of raising farmers’ and fishers’ incomes.

- Sufficiency should not be pursued at all costs, as food security and agricultural development have many other needs that require budget support.

- Food security requires working on poverty reduction for all sectors, not only those directly involved in food production and distribution. This implies that food security is not the sole responsibility of the Department of Agriculture (DA).

Food security and competitiveness

Competitiveness is achieved incrementally and needs to cover other food items.

Achieving competitiveness in food items is more contentious and has been at the root of the food security and food sufficiency debate.

Food access by individuals and families is determined by food prices and food purchasing power (individual and family incomes), while food availability depends on the capacity of food producers to provide staples and common food items, including vegetables, fruits, fish, eggs, meat, etc.

The debate between food security and food sufficiency has unnecessarily narrowed the understanding and strategy toward availability of and access to food. For example, analysts have tended to trace all food inadequacies to the unresolved debate and to protectionist tendencies.

Likewise, while food inflation is a closely watched indicator, it is inadequate in terms of measuring how well a country is ensuring food for its people.

According to a paper by Raul Montemayor, the expenses on local production should not be used to justify more imports.

“The fact that imports are cheaper is not a sufficient reason for relying on them instead of local production,” he wrote.

“Local production may be more expensive because it is not provided adequate support from government. But it could have the potential to be competitive, given sufficient support,” he said.

“Relying on imports just because they are cheaper will deprive local producers the opportunity to reach that potential. Also, price should not be the only consideration,” Raul wrote.

“Imports may be cheaper at present but could become more expensive or unavailable later (as happened to corn and rice). These risks, and not only comparative prices, should be taken into account in determining the safe and proper level of domestic food sufficiency,” he said.

Protectionism, according to Raul, “was never meant to be an import ban but rather a means to manage and calibrate imports so that local supply deficits could be addressed while preventing excessive surpluses that would unduly depress prices for producers.”

“Local prices do not necessarily have to rise significantly when the domestic market is protected,” he said. “If the entry of imports is managed well, and a way is found so that importers and traders actually pass on the benefits of cheaper imports to consumers, consumer prices will remain stable and could even go down without significantly depressing producer prices.”

Another expert, Gerry Bulatao, said food means much more than rice.

“The food security framework must include other food staples: white corn, camote, cassava, bananas, Adlai,” he wrote in comments for this paper.

“Overconsumption of rice may lead to diabetes. Depressing the demand for rice increases its sufficiency level,” he wrote.

There should be focus, Bulatao wrote, not only on basic production but also millers, traders and consumers.

Production targets, he said, should include vegetables. “Should we not aim for a higher level of sufficiency in mongo, onions and garlic, among others?” he wrote.

This, Bulatao said, should also include fruits which are “excluded from food security.”

Other industries that should be in food security discussions are sugarcane, poultry, livestock and dairy, fisheries, food manufacturing and coconuts.

According to Bulatao, while copra is not considered food, coconuts should be included in a food security framework because of these:

- Since among the factors for food security is affordability, there should be programs for coconut farmers, who are among the poorest in the Philippines. While copra prices had rebounded to P40 per kilo, coconut farmers have seen prices plunge to P6 per kilo and stopped harvesting.

- Land between coconut trees is useful for food production—vegetables, fruits, poultry, livestock, napier grass and other feed stock.

- Coconut-based products can be considered food or raw materials for food—buko, buko chips, coconut water, vinegar, coco sugar, cooking oil, etc.

To understand rice competitiveness better, the long proposed benchmarking study was finally funded by the DA and conducted by PhilRice and IRRI with the results contained in the report “Competitiveness of Philippine Rice in Asia”.

One finding of the study was that the Philippines’ expense on labor in rice production was considerably higher than that in other countries. This reinforced the belief that higher levels of mechanization can bring down the cost of production. It is good that the DA now sets the target for mechanization in terms of horsepower per hectare.

Marketing costs also ranked highly. Addressing these would involve reducing post-harvest losses, improving milling efficiency, modernizing marketing infrastructure (roads, bridges, ports) for agricultural products and ensuring free competition in markets. But other countries employ hidden subsidy that makes their rice cost lower. Comparisons based solely on prices tend to be unfair to Filipino rice farmers.

Making comparisons with other countries based on final figures—on food security, production, price, inflation and so on—is useful. But even more helpful would be to dig deeper and to look at the realities underlying final figures to determine where exactly the Philippines or the sectors are lagging behind, what can be done better, or where progress can be attained faster.

Regular updating of the rice comparative study will help track progress and ensure that compared costs across countries take subsidies and natural endowments into account.

Targeting levels of yield and cost of production for various crops has been recognized as critical in taking steps towards competitiveness. For rice, the proposed target was Sais-Otso (yield of 6 metric tons per hectare and P8 per kg as cost of production). This has been achieved in Nueva Ecija. Can it be made the national standard, even as the goal for Nueva Ecija is raised?

The DA has published commodity digests that documented standard yields and costs of various food crops including onions, cassava, cacao, coffee, rice, seaweed. These need to be updated and expanded to cover other crops.

Something similar should be done for poultry and livestock products. Each commodity or product should be subjected to a value chain analysis (VCA), which will serve as a basis for setting production, cost of production, price and income targets. The DA already has a number of these VCAs as part of the implementation of the Philippine Rural Development Project (PRDP).

There is a growing acceptance that food security policies and programs cannot be limited to one administration but must be carried forward by the next.

Rather than the subsequent administration ignoring or denying gains achieved by its predecessor, it is important to build upon the previous leadership’s achievements.

What is important is to ensure an effective feedback mechanism so that all stakeholders—be they farmers, fishers, bureaucrats, scientists, NGO workers, entrepreneurs large and small, bankers and financiers, traders, logistics providers and workers, or consumers—can help identify interventions and approaches that work and don’t work.

The impact of the Rice Tariffication Act needs to be monitored closely to include prevailing palay and rice prices in various parts of the country and not simply accept the aggregate figures reported by the Philippine Statistics Authority. This tracking is also being done. Anecdotal evidence can reinforce the findings of studies or be used to raise questions for clarification.

What can be done quickly

Approaches to support services delivery have to include all stakeholders from design to implementation and provide for quick response. There is no perfect delivery system for support services in the agri-fishery sector. Perfection can be approximated but never attained. The most an agency can do is move toward it. Every administration tries to do its best, but there will always be gaps, areas that need improvement.

For example: FIELDS (Fertilizer, Irrigation, Extension, Loans, Dryers and Seeds) represented a comprehensive and integrated package of services under the Ginintuang Masaganang Ani program of the Arroyo administration. Until today, these are still among the components of support services. But they have been enhanced over time.

- Fertilizers were subject to centralized procurement. This was decentralized to reduce corruption. A “buy-one, take-two” voucher system involving Irrigators’ associations and farm supply stores has been proposed as a more efficient way to distribute fertilizers to farmers. (A refinement of this method, which can also be applied to seeds, is to distribute vouchers—similar to SM gift checks—and allow the farmer to purchase his choice of types, brands or varieties and add his own cash if needed.)

- Irrigation has been the domain of the National Irrigation Administration, which is still under the Office of the President, but the Bureau of Soils and Water Management is responsible for small water impounding systems and shallow tube wells.

- Extensionis still the responsibility of the Agriculture Training Institute (ATI), which has further developed its course offerings. Initiatives of TESDA (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority) on courses granting national certificates for agriculture crop production, fish capture and wharf operations are welcome.

- Loans are delivered in various forms to suit target groups and commodities with terms redesigned to include a loyalty scheme that ensures cheaper loans, as farmers establish their reliability as conscientious borrowers. Loan programs build in risk mitigation mechanisms like crop insurance for farmers and guarantee funds for banks.

- Dryersstood for mechanization and led to the subsequent introduction of combine harvesters, reapers, tram lines and other farm machinery. PhilMech has been challenged to increase further its involvement in mechanizing agricultural production to reduce costs.

- Seed development has been the responsibility of PhilRice but under the Rice Tariffication Act, the agency has been asked to ensure proper distribution of seeds and has been promoting seed growing in new areas for faster response in the event of a calamity.

Cutting across the various support services is the Registry System of Basic Sectors in Agriculture (RSBSA) that helps identify and track farmer-beneficiaries. The system needs to be maintained and updated, for it to continue to be useful. It must also involve the barangay so farmers can check whether they are properly listed and initiate inclusion or exclusion processes as needed.

No component of support services is foolproof. Safeguarding against unwanted results requires a steady stream of feedback from the final recipients of the services. Some organizations continue to feel that the DA does not provide sufficient support, while some budget allocations have been found to be underspent.

Encouraging farmers to group themselves into clusters, associations or cooperatives is vital for enhancing participation and improving feedback.

“Rowers” can be “Steerers,” too, within their scope of responsibility for a particular sector or LGU, and when they give feedback to policymakers and propose solutions to problems they understand best. “Steerers” should be “Rowers” themselves in feeling the pulse of the grassroots and in being grounded, not remaining in the clouds and issuing policies like lightning bolts that may be irrelevant.

The Food Security Summit may also try to prioritize some major interventions beyond direct support services that include:

- Food security requires appropriate infrastructure.The backlog of over 10,000 kilometers of farm-to-market roads (FMRs) should receive support. LGUs and barangays can be encouraged to supply the road network maps for these FMR projects. DA can supply geotagging support.

- Mechanization should encompass the food value chain. It should include promoting and training of service providers to maintain the machines and systematize servicing of individual farms. It should include basic food processing of farm produce and support for food development. The cold chain system and the installation of powdering facilities can be added to existing community fish ports and other production sites.

- Research and developmentthat delivers ground-level results need support.This can refer to applied research and the training of scientists who are oriented to providing crop and product support. Lagundi, VCO, coco water, blast-frozen fish, bio-diesel are a few examples of products that can be developed further, but how farmers and fishers may benefit beyond being suppliers of raw materials needs to be considered.

- Consolidation of certain activities can enhance productivity and profitability.These may include block farms, shared processing facilities, service provider groups to maintain farm machinery and operate leasing services, consolidated marketing efforts, farm planning and crop scheduling, and more.

- Organic agriculturedeserves space in the food security framework.It need not be embraced as a religion, but its positive impact on the creation of healthful foods and reduction of production costs for certain commodities should be recognized and supported. There is a niche market for these products, and it is growing. Likewise, organic fertilizers and non-synthetic-chemical concoctions used as growth stimulants and natural pesticides should be acknowledged as helpful.

- Setting targets need not mean agreeing on a particular point or number. The target may be a range of numbers, especially when an agency is not the only entity responsible for creating an outcome. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas sets a target range for inflation. The DA may likewise set a target range for palayproduction, cost of production, rice price and farmers’ and fishers’ incomes.

- Linkage to markets is very important. This includes shortening the value chain, allowing farmers to value-add, and connecting them to stable markets.

- Integrated and sustained location-specific interventions. Current initiatives have little impact because they are piecemeal, compartmentalized and not sustained. Thus, the benefits from one intervention get offset by losses due to the absence of other equally important interventions. Plus, many of the interventions are not specifically designed for the problems and priorities of specific areas.

Partnership Needed

It is hoped that the views of farmer organizations, as expressed in this paper and related submissions, will be seriously considered and will be informative for future actions, policies and programs. Active collaboration toward the achievement of Food for All is our desired outcome.

(Editor’s note: Leonardo Q. Montemayor is president of the Federation of Free Farmers. He was agriculture secretary and also board chair of the Philippine Coconut Authority from 2001 to 2002)