Artwork by: Marie Faro / INQUIRER.net

It is undeniable that education was among the sectors changed so drastically by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Schools nationwide were forced to close when physical classes were considered too risky to hold as SARS Cov2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is transmitted mainly from human to human and whether vaccines would be available remained uncertain.

Confronted with this, the Department of Education (DepEd) turned to what is now known as blended learning for school year 2020-2021

The DepEd solution required schools to shift from conventional to “hybrid” learning, so called because it involved a mix of distant online learning and modules delivered to students’ doorsteps or picked up from DepEd sites.

Electronic media delivered by the internet, radio and TV broadcasts to mobile devices, computers, TV and radio sets became a necessary component of blended, or hybrid, learning.

The DepEd had planned to open classes under the new normal on Aug. 24 but it has since been moved to Oct. 5 to give teachers and learners more time to prepare for the new system.

But since the DepEd announcement of the shift to blended learning last May, questions linger about its effectivity. Doubts were also raised about the country’s preparedness for the major shift in learning.

As challenges and criticisms pile up, a question stands out: Will the new learning system work?

Blended learning, according to Education Secretary Leonor Briones, should not come across as a strange thing. According to her, the concept is not new.

Briones said some schools and universities had been offering blended learning “for decades.”

“We have been doing distance learning, blended learning for decades and decades,” Briones said. She cited the University of the Philippines (UP) as an example. UP, she said, has been offering and specializing in “distance education for the longest time.” “Those who take up education and study education are already exposed to this,” she said.

“We are not inventing anything new,” Briones said at a televised briefing in Malacanang last June.

Aside from being used as a temporary solution for schools and classrooms shuttered by the pandemic, blended learning could also address the problems that have been perennially plaguing conventional learning.

Among these are lack of teacher and facilities and other problems that blended learning could address.

Blended learning requires students to attend classes at home, which would prompt parents to be capable of helping their children on lessons.

Reality, however, would sink in for those who neither have the financial means, nor the time, for blended learning.

Enrolment in the current school year started last June 1 by text messaging or online means.

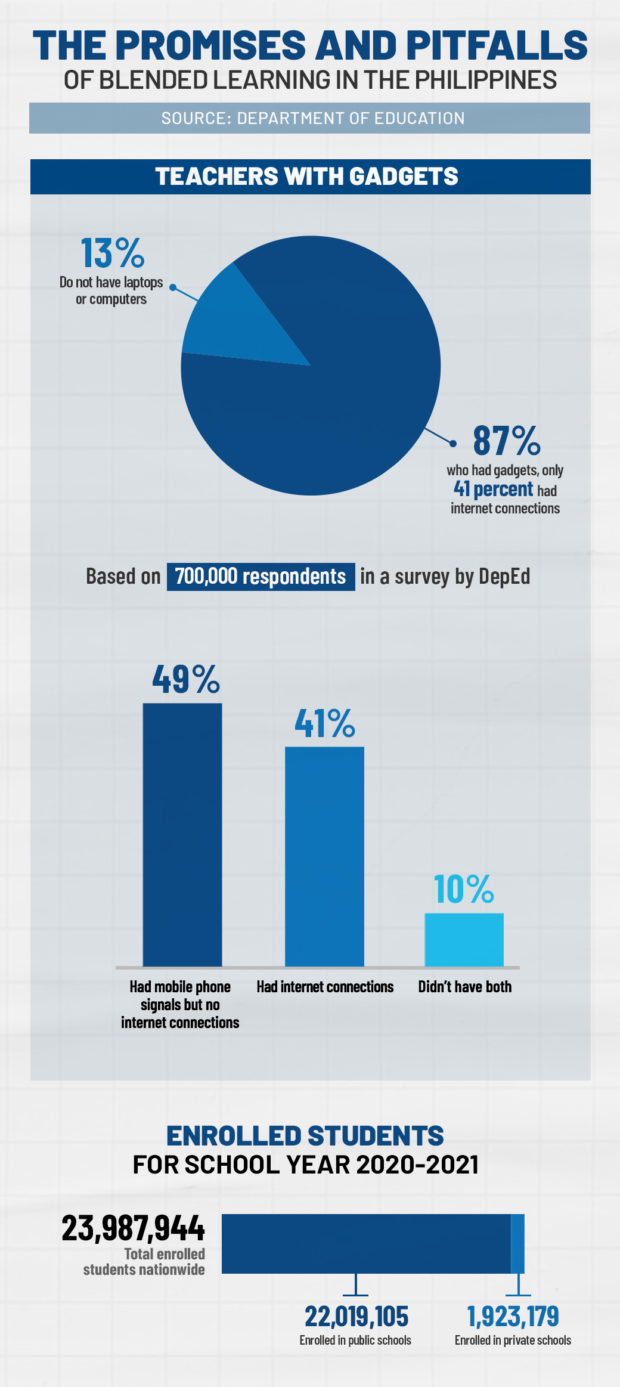

As of last September, the DepEd said enrolment in public and private schools had reached 23,987,944 students nationwide. At least 22,019,105 had enrolled in public schools while 1,923,179 in private schools.

The DepEd also reported that over 1 million devices and gadgets, tools for blended learning, had been received by 93 percent of teachers and students nationwide.

Infographic by: Ed Lustan / INQUIRER.net

But a survey by the department showed that majority of 700,000 teachers still lacked gadget and internet access, which are necessary for blended learning.

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) cited the survey in a report, saying 13 percent of respondents did not have laptops or computers. Out of the 87 percent who had gadgets, only 41 percent had internet connections.

The survey also found that 49 percent had mobile phone signals but no internet connections in their households. At least 10 percent didn’t have both.

The difficulties of access to information communication technology (ICT) are felt most by students. Children from impoverished areas were likely to be at a disadvantage at the start of classes.

Grade 7 pupil Mark Joseph Tabago uses a borrowed mobile phone as a means to confer with his teacher from his home in Barangay Pinyahan in Quezon City. (Grig C. Montegrande/Inquirer)

Aside from difficulty in access to internet services with enough speed for blended learning, increasing internet subscription costs also hound learners and instructors. Hardware and software, must haves in blended learning, could be costly to everyone—educators, students and parents.

At a televised press briefing in May, Education Undersecretary Nepomuceno Malaluan claimed that parents were not required to buy gadgets for their children. For those with no devices, schools would provide learning modules.

As of September, DepEd reported that 533 million sets of self-learning modules had been distributed.

The department also tapped TV and radio channels for blended learning, asking them to devote at least 15 percent of their airtime for lesson broadcasts.

Education Undersecretary Tonisito Umali said 3,120 television lessons and 3,445 radio episodes were set to air in 2,017 TV channels and 162 radio stations nationwide.

But while blended learning simulations, which had drawn 500 public schools as participants, had been declared a success, errors in learning modules and lessons had drawn probably bigger attention.

The DepEd had been thrown into a pot of embarrassment recently when netizens pointed out a mistake at a learning episode aired by DepEd TV recently which featured a mathematical equation with an incorrect solution.

This was not the DepEd’s first brush with embarrassment over lesson errors.

Last August, sharp netizens’ eyes also pointed to grammatical errors in a sample questionnaire for a Grade 8 English course.

As criticisms pile up over its version of mixed learning, the DepEd tried to clarify that it was not claiming success.

Briones said the department would monitor progress in the learning system and make an assessment before the end of the year.

“We are not claiming the success of blended learning, which is a learning modality older than I am, where various techniques are utilized,” Briones said at a Palace briefing.

“Right now, we are monitoring whatever is happening. In a month or two, before the end of the year or even earlier, we will have a formal assessment,” she added.

She also sought to give assurance that the DepEd would address problems “as they come.”

Pasig City’s Community Learning Hub assists pupils needing tutorial assistance. (Pasig PIO)

As DepEd struggles with blended learning woes, several local government units (LGUs) had stepped up to the plate to help learners and teachers.

Taguig City recently opened what it called Tele-Aral Center which sought to address the distance learning needs of students and parents struggling with blended learning issues.

Makati City distributed flash drives to students.

The city government of Manila is providing free access to online learning platforms through a telecommunication firm’s program. At least 11,000 LTE pocket mobile Wi-Fi transmitters had been distributed to public school teachers.

TSB