Ampatuans on trial ‘filed every motion they could’

ILLUSTRATION BY RENE ELEVERA

(First of three parts)

For almost a decade, the weight of numbers has haunted the trial on the Maguindanao massacre, the single deadliest attack in history on journalists and the worst election violence in the Philippines.

Inside Branch 221 of the Quezon City Regional Trial Court, 238 volumes of records of court proceedings, transcripts of stenographic notes, and documentary evidence fill layers upon layers of cabinet drawers.

In the courtroom, the sight of thick document folders for the murder case against Datu Andal Ampatuan Jr. and 196 others has daunted even the most dedicated lawyers.

But the image of 58 corpses buried in a pit dug by a backhoe on Nov. 23, 2009, at hilly Sitio Masalay in Maguindanao province continues to haunt the entire justice system. The casualties, including 32 journalists, were part of a convoy of then Maguindanao gubernatorial candidate Esmael “Toto” Mangudadatu, who was to file his candidacy in the June 2010 election against Ampatuan Jr., then town mayor of Datu Unsay.

Article continues after this advertisementBefore the case was finally submitted for resolution on Aug. 22, the court had heard a total of 357 witnesses—134 from the prosecution and 165 from the defense, and 58 private complainants. The proceedings, led by Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes, were actively attended by 11 lawyers comprising the third panel of public prosecutors, six private prosecutors and 20 defense lawyers.

Article continues after this advertisementThe prosecution presented a number of eyewitness accounts of the murder of the victims in the Mangudadatu convoy, how the Ampatuans supposedly planned the murder, the presence of checkpoints in Masalay, and testimonies establishing the political rivalry between the Ampatuans and the Mangudadatus as motive for the massacre.

Authenticated video footage found during the excavation of the massacre site, as well as the retrieval of the bodies at Masalay, were also presented in court.

Crucial testimonies

One of the most crucial testimonies came from Sukarno Badal, former vice mayor and a commander of the Ampatuans’ private armed group, who narrated how members of the powerful political clan planned to kill the victims.

In his witness account, Badal said the Ampatuans had prepared three separate plans on their attack on the convoy, depending on where Mangudadatu would file his certificate of candidacy—in Cotabato City, in Manila, or in Shariff Aguak.

Cpl. Zaldy Raymundo of the Army’s 38th Infantry Battalion, who was stationed in the military outpost at Masalay, also told the court that he saw policemen and armed civilians conducting checkpoints in the area on the day of the massacre.

Raymundo said he saw a convoy of vehicles stopped by the group and brought to the hilly side of Masalay, from where he heard gunshots. He also said he saw a backhoe driving up to the massacre site.

Efren Macanas Jr., one of the backhoe drivers, said it was an aide to the Ampatuans, Bong Andal, who had ordered him to drive a backhoe to the mass grave.

Judge Solis-Reyes was to have handed down her verdict on the case by Nov. 22—a day before the 10th anniversary of the massacre. But the sheer volume of the case files that the court had worked on in the course of the trial forced the judge to request from the Supreme Court another 30 days to work on her decision.

The families of the massacre victims have to wait until Dec. 20 for closure. (See related story on Page A6)

“We know that we have submitted enough evidence to convict the accused,” said private prosecutor Nena Santos, who represents 38 of the 58 victims in the case. “Conviction may not be possible for all, but we are hoping that at least the principal accused [would be convicted].”

For Santos, the case took almost a decade because the defense exhausted procedural and extralegal strategies that prevented speedy resolution.

“They filed every motion they could file, changed their lawyers whenever a major resolution was on the way, and even filed cases against witnesses and prosecutors,” Santos said. The lawyer has stood with her clients and hundreds of witnesses even as some of them, she said, were offered bribes to recant their testimonies against the accused.

Change of lawyers

Since the trial began in 2010, the Ampatuans had presented 165 witnesses and changed their lawyers four times.

Sigfrid Fortun served as their lead lawyer from 2009 to 2014. Salvador Panelo, now spokesperson for President Duterte, stepped in next, but his stint ended in December 2015. He was replaced by Andres Manuel, who withdrew from the case in 2016. Raymond Fortun represented the Ampatuans for the next three years until he withdrew as lead counsel just before the trial ended.

It was only when Judge Reyes ordered Ampatuan Jr. in August to find a new lawyer that private lawyer Paul Laguatan took on the case.

Throughout the trial, the Ampatuans maintained that they were only framed by their political rivals and that they had no hand in the massacre.

On Oct. 14, Ampatuan Jr., through his new lawyer, sought to reopen the trial with a motion to suspend the promulgation of judgment. He claimed in his motion that prosecution witness Badal had approached his representative and wanted to recant previous testimonies.

Badal denied the allegations in the motion, which was eventually rejected by the court.

Out of the 197 accused for murder, 117 were arrested, and 80 remained at large.

Ninety of the 117 arrested are still in jail, including primary suspects Ampatuan Jr. and Datu Zaldy Ampatuan. Their brother, former Maguindanao Gov. Datu Sajid Islam Ampatuan, is out on bail.

Their father, Andal Ampatuan Sr., who had liver cancer, died from a heart attack on July 17, 2015.

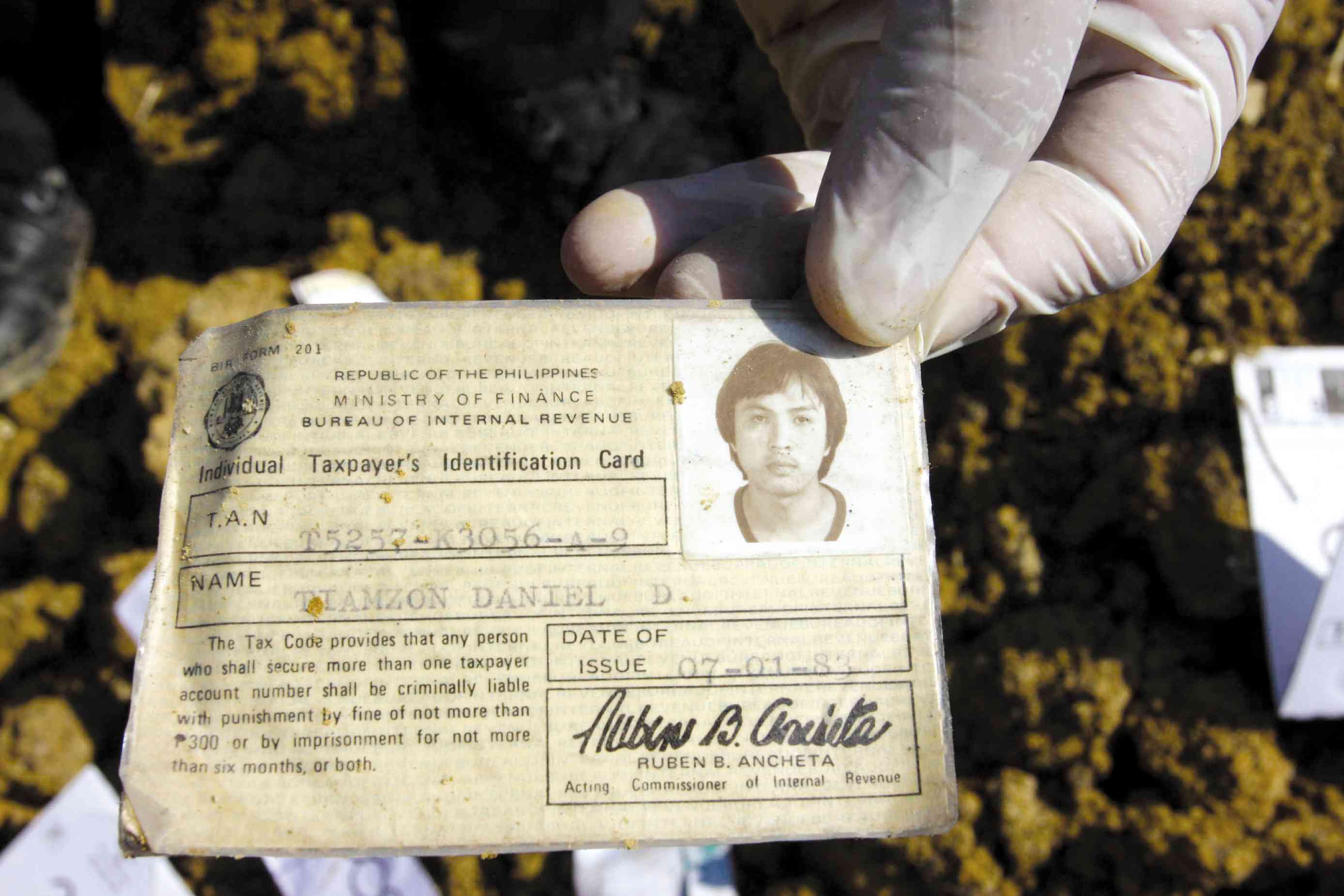

NEARING CLOSURE TheQuezon City Regional Trial Court is to finally pass judgment on Dec. 20 on 197 people accused in the

worst election violence in Philippine history. Of the 58 victims of the Maguindanao massacre, 32 were journalists like Daniel

Tiamson of UNTV, whose ID card was recovered at the site of the killings. —INQUIRER PHOTO

Severe chilling effect

The Committee to Protect Journalists described the Maguindanao massacre as the single deadliest event for journalists in history. In its immediate aftermath, the massacre had a severe chilling effect on other journalists, especially among the victims’ colleagues, according to Nonoy Espina, president of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines.

“It also highlighted what we had been saying even before the massacre—that the system of governance in the country, in which the central leadership often chose to close its eyes to the abuses of local political lords whose support it needed, created the conditions that made the slaughter possible,” Espina said.

He said that even with the “horrifying magnitude of the massacre,” killings and other assaults on journalists and the freedom of the press had continued.

Lawyer Santos worried that while the Ampatuans’ scope of influence had waned over the years, some members of the clan were still wielding power in Mindanao.

“But at the end of the day, it’s the people that matter—not a political clan,” she said. “If there would be no conviction, I’m sorry to say that press freedom in the Philippines is dead because impunity triumphs.”

(To be continued)