The ‘Arsenic’ made Manila among the world’s finest

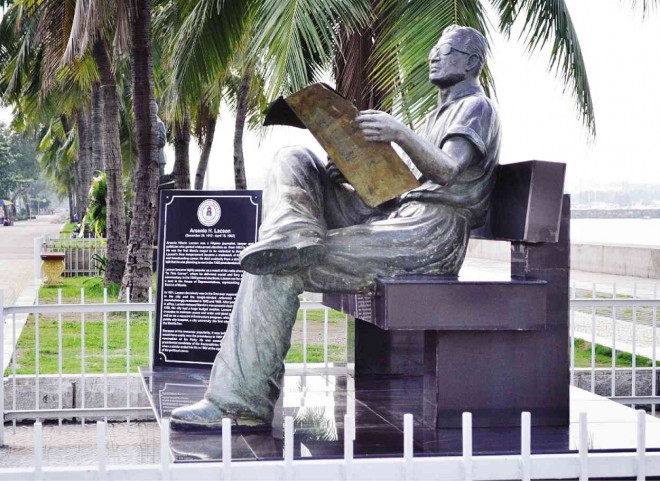

The Julie Lluch masterpiece has regained its limbs and place of honor on Roxas Boulevard. The sculpture, which captured Lacson in his trademark aviator sunglasses and reading a broadsheet on a park bench, was completed by Julie Lluch in 2003, after being commissioned by then Mayor Lito Atienza. MANILA CITY DEVELOPMENT INFORMATION OFFICE

On Holy Thursday, April 15, 1962, while it was in the midst of observing Lent, the entire country was shocked by the news over radio that Manila Mayor Arsenio H. Lacson died of a heart attack inside Hotel Filipinas in Ermita.

His death brought to an end the golden age of Manila’s restoration as a premium city, efforts presided over by Lacson for 11 years since he was elected to City Hall in 1951. The capital city had been devastated by World War II and needed rehabilitation badly.

We heard the news on board an interisland ship on our way to Bacolod City, in the home province of Lacson. The Negrense born into the sugar gentry class rose to dominate national politics, using Manila as his power base.

Lacson’s rise to a preeminent position of power and influence in national politics depicts the legendary transformation of a politician who had managed to scale the commanding heights of power from his humble provincial, economic and social origins. His story resonated with me not because he was a fellow West Visayan, but partly because he was a newspaperman who sought public office to pursue his goal of using politics as a medium with which to deliver an honest and effective governance, and by using his remarkable skills as a journalist.

Son of Manila

The story of this transformation is narrated in the first biography of Lacson titled “Arsenio, Son of Manila,” written by Amado F. Brioso Jr., a Filipino bank official based in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Brioso was moved to write the book after an exhaustive research during a visit to Manila in 2012, into Lacson’s remarkable career. His research led him to conclude that “this great figure … could have been president of the Philippines.”

The book, released a week ago, might well be a story of the life and times of Arsenio Lacson, which shaped his writings and defined his political career, first as a member of the House of Representatives representing the 2nd District of Manila with such distinction so that two years later, he was cited by journalists covering Congress as one of the “Ten Most Useful Congressmen.”

1st mayoral election

In 1951, in Manila’s first mayoral election, Lacson defeated the administration-supported incumbent Mayor Manuel de la Fuente in a landslide victory that swept out nearly all the Liberal Party councilors and established his dominance in capital-city politics.

To most media observers, Lacson appeared as a fresh gust of wind, a wave of change that cleared the way for cleaning up corruption in City Hall and for speaking up against the abuses of national administrations in Malacañang. Prior to his entry into congressional politics, Lacson was an outspoken journalist whose ascerbic columns (titled “In This Corner”) savagely lacerated sitting presidents and earned for him the sobriquet “Arsenic,” as well as suspensions for broadcasting his tirades against governments.

Lacson was an unconventional politician and newspaperman, and a pugnacious commentator on public events ranging from corruption in municipal governments to such issues as foreign affairs and nationalism.

Brioso’s book covers not only those aspects where Lacson exercised his devastating critiques. It also examines details of Lacson’s private life and his flaws as a principled politician working within the constraints of the Philippine democratic system. The book depicts Lacson as a pugnacious and extremely articulate politician. But warts and all, he had his human side.

Football star

In this book, Lacson comes off as a combative character whose journalistic talents highlighted his predeliction for getting involved in encounters with prominent political authorities, this being the staple of his public discourse. Few of his adversaries could match Lacson’s venomous prose in public debate. As the book reveals, Lacson received excellent academic education at the elite University of Santo Tomas, where he graduated with a law degree. After passing the bar, he served as prosecutor at the justice department. The heir of sugar hacenderos in Talisay, Negros Occidental, proved that their wealth was not wasted on the education of their talented protégé.

Lacson had other talents and interests aside from being devoted to his law studies. He engaged in campus athletics and was a star football player in the Ateneo football team (football being the favored sport of the sons of elite families in Negros and Iloilo). He was also a star player of the Philippine football team sent to the Shanghai Far Eastern Olympics in the 1920s. He trained as an amateur boxer, which gave him the capacity to beat bullies who included would-be Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, who once declined Lacson’s challenge to a fistfight over their rivalry for women. His broken nose was an upshot of some of those boxing encounters.

Best cities

During Lacson’s second mayoral term, a group of American mayors cited Manila one of the best cities in the world, the only city deemed as such in Asia.

The 10 years that Lacson served as mayor of Manila were filled with accomplishments, foremost of which was the liquidation of a P21-million City Hall debt incurred by the previous nine administrations.

Lacson expressed in his own words a principle he lived by during his mayorship: “It has always been an inflexible principle with me that personal friendship and partisan loyalties do not count in the face of public interest. Wherever (the) fundamental welfare of the people is concerned, I recognize no loyalty to any man, woman or child, but only to the nation as a whole.”

RELATED STORIES

Arsenic’ back at Manila City Hall, marks Estrada bid for new Golden Age

Mayor Arsenio ‘Arsenic’ Lacson gets his arms back

Kin of beloved Manila mayor rue neglect of ‘Arsenic’ image