‘Garbage in, garbage out’ policy keeps Hundred Islands clean

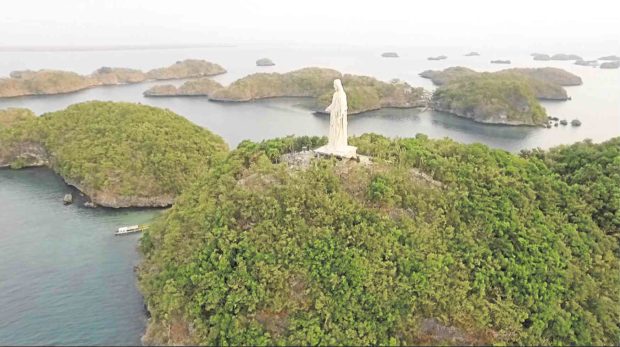

Hundred Islands National Park in Alaminos City, Pangasinan province, is among the top tourist drawers in the Ilocos region. —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

ALAMINOS CITY — When Amy Ferrer and her family went to Hundred Islands National Park here, they were given two plastic bags for which they had to deposit P200.

“We were told that it was for the garbage that we would generate on the islands. We would get a refund when we bring the garbage back to the mainland. We did get our P200 back,” Ferrer said.

The refundable fees for garbage bags recycled from used tarpaulin encourage visitors to surrender their garbage, thus keeping the national park free of wastes, according to a local conservationist.

“[The program] is called ‘Basura mo, iuwi mo’ (Bring your trash home),” said retired Supt. Manuel Velasco, commander of Task Force Isla, which enforces policies and rules on security, protection and preservation of Hundred Islands National Park.

Under the project, a group of visitors is given two garbage bags — one for biodegradable waste and the other for nonbiodegradable materials.

Article continues after this advertisementTarp bags

Article continues after this advertisementThe daily average volume of collected biodegradable wastes is 20 to 40 kilograms while nonbiodegradable wastes average 16 to 20 kg.

The garbage bags were sewn together by inmates at the city police jail, enabling them to earn while in detention, said Rose Aruelo, tourism operations officer.

Each bag is enough to accommodate trash of up to 25 tourists sailing around the islands.

The tourism office has set aside 400 garbage bags for February tourists and has commissioned the production of 1,500 bags.

When the tarpaulin bags run out, tourists are given black plastic garbage bags.

At the end of the day, or when their boat docks at Lucap Wharf, visitors submit their bags at a booth and redeem their deposit money.

As another incentive for tourists to keep the islands trash-free, they are given two free entrance tickets. Their environmental fees are also waived.

The tickets and environmental fees are worth P70 each, and can be used on their next visit to the islands or given to other people as these are transferable.

‘Scubasurero’

“Bangkero” (boat operators) are not allowed to surrender the garbage as the practice could be abused, Velasco said.

Aruelo said some tourists did not return the garbage bags, foregoing their deposits, to keep them as souvenirs.

Some tourists still have not imbibed waste segregation as they still mix biodegradable with nonbiodegradable, she said.

But many also appreciate the “Basura mo, iuwi mo” concept, like Ferrer who said “the conscious effort to keep the islands clean is paying off as there are less garbage there.”

The process will take time. Plastic cups and wrappers still litter the islands as well as their waters.

Plastic wastes find their way to the seabed and marine animals mistake these for food.

This is where the “scubasureros” come in, Velasco said.

The scubasureros are scuba divers who collect the garbage underwater.

“We do this once a month,” said Velasco, a certified scuba diver.

The waters off Quezon Island, the most developed and visited island, used to have the worst garbage crisis until the “Basura mo, iuwi mo” was strictly implemented.

Food wrappers

But litter still plagues Cuenco Island, which is less supervised.

On the seabed, scuba divers collect mostly plastic materials like water bottles, spoons and forks, “sando” bags and wrappers of snacks, biscuits and cookies.

In October last year when the scubasurero project was launched, divers gathered about 50 kg of garbage.

“Now, it’s just about 30 kg,” Velasco said.