Caloocan cutthroat murders: Short-lived friendship ends in tragedy

A mother’s final kiss: Mary Jane says goodbye to son, Harold Bulan.—PHOTO BY Aie Balagtas See

When Mary Jane, a vegetable vendor in Caloocan City, bought a life plan for herself three years ago at the urging of her son, Harold Bulan, she had no idea she would use it to bury him.

At 3:20 a.m. on Nov. 22, the bodies of 17-year-old Bulan and his cousin, 15-year-old Jericho Garcia, were found on the sidewalk on Edsa’s northbound lane, near General Mascardo Avenue, in the city.

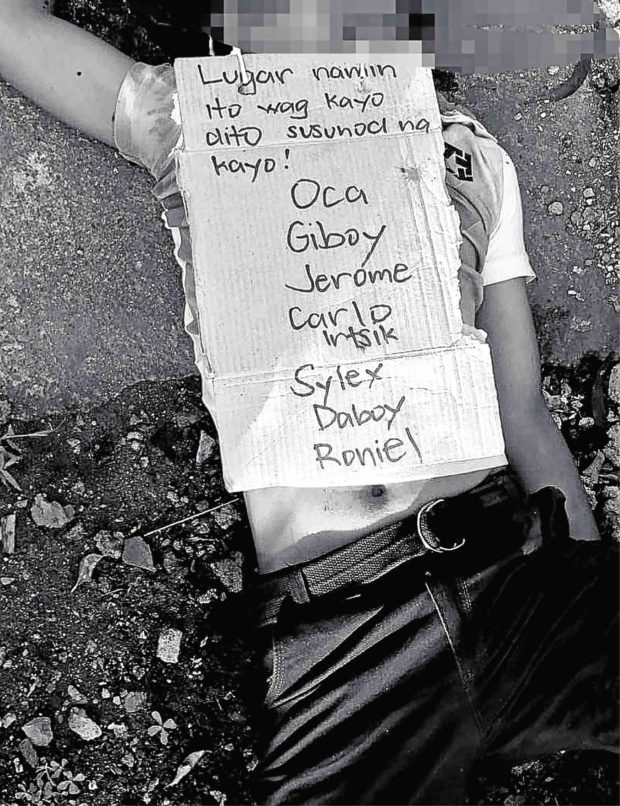

Hanging from Bulan’s chest was a cardboard sign with the message: “Lugar namin ito, ‘wag kayo dito, susunod na kayo (This is our territory, keep out, you’re next),” followed by the names of eight boys whom the police have yet to identify up to now.

Almost an hour later, the body of Jomari Sinerez, 16, a friend of the two boys, was discovered on Dagat-dagatan Extension, also in the city.

According to the police report, someone had slit the throats of the three boys who bonded in July after they were admitted to the Molave Youth Home in Quezon City, a shelter for children in conflict with the law.

Article continues after this advertisementNone of the boys were on the Caloocan police’s drug watch list although authorities have yet to determine if they had previous criminal records.

Article continues after this advertisementFor now, they are believed to have been killed by still unidentified suspects over a turf war with a rival street gang, said case officer PO1 Mark Julius Pajaron.

Police have not identified the boys listed on the cardboard sign left on Bulan’s body.—Inquirer file photo

Last text message

Two days before he died, Bulan sent a cryptic text message to his girlfriend, Isabela (not her real name). It said, “‘Hal (short for Mahal), nahuli kame (Love, we got caught).”

Isabela replied with a barrage of text messages, each one pressing him for more details.

A minute later, she received a mocking and final reply: “Patay na siya. Kawawa naman. (He’s dead. What a pity.)”

Alarmed, Isabela, together with the girlfriends of Sinerez and Garcia, rushed to three police stations in Caloocan City to find out if they were being held there.

“He [Bulan] said they got caught so we assumed they were under police custody,” she said.

The girls did not find their boyfriends but Isabela refused to believe they were dead.

It was not until Nov. 22 that the truth sunk in when their bodies were found.

“We just got together. He promised that he would never leave me. But he left so soon,” she told the Inquirer.

Isabela wasn’t the only woman grieving over Bulan’s death. His loss was also a big blow to his mother who admitted that of her six children, he was her favorite.

“I lost a good son, the only child who truly understood me,” Mary Jane said.

“I didn’t have to ask him to do chores or to help me. One time when I was confined in the hospital, he immediately brought me food and clothes. I didn’t have to ask him. He just knew [what to do]. He was also his sister’s babysitter,” she added.

Bulan was the ideal son who fell in with the wrong crowd, she said. She did not elaborate, only adding that his friends “were not good people.”

According to her, her son started hanging out with his “bad friends” after his father was killed two years ago.

But Jeremy, Sinerez’s brother, said it was the other way around. He admitted though that Sinerez, the eighth child among 13 siblings, was taken to the Molave Youth Home in July for a case of attempted homicide.

His brother got out in August after reaching a settlement with the complainant, Jeremy told the Inquirer.

Sinerez had figured in a street brawl in Balintawak where one of his friends handed him a gun and urged him to shoot the complainant. Sinerez ended up shooting the victim in the back.

While in Molave, Sinerez met Bulan and Garcia, Jeremy said, adding that he did not know why the cousins had been admitted there. But by the time the three boys got out, they were already fast friends, he said.

According to Jeremy, he had suspicions that his brother may have been involved in questionable activities. But he insisted that it was Bulan and Garcia who had been a bad influence on his brother, not the other way around.

Before his death, Sinerez had been working odd jobs at the Balintawak market where he was known as “Babyboy” because of his boyish good looks.

“You can ask anyone there, my brother was a good man. He was the only one who helped me earn money for our family especially since both our parents have left us. If ever he got involved in anything, it wouldn’t have been on his own,” Jeremy claimed.

Weeks after he was killed, Bulan was finally buried at Manila North Cemetery on Dec. 9, the eve of International Human Rights Day.

The funeral took Mary Jane back to that fateful day three years ago when her son asked her to buy a P650-a-month life plan for herself.

Life’s twist

She recalled that Bulan had told her: “Why don’t you get a life plan so we wouldn’t have to worry when you die? Plus, you leave some money behind.”

But since the five-year plan had yet to mature when her son was killed, the company told her she was not qualified for the P300,000 payout.

“They can have the money, I don’t care anymore. What’s the use of money when my favorite son is already dead? With his death, his killers essentially killed me, too,” she said.

To give Bulan a decent funeral using her life plan, she had to pay P23,000 more, an amount she raised by borrowing money.

But when they got to the cemetery, the undertakers refused to bury her son unless she paid P12,000 more since he was being buried in a private lot beside his father.

The funeral proceeded only after Mary Jane’s father gave P5,000 as down payment while she promised to leave their motorcycle as collateral.

Outraged, she refused to watch as they placed her son in the ground. But before they did, she asked them to lift the coffin cover so that she could kiss him one last time.

As she embraced her son, she told him: “Son, my son, mama loves you so much.”