Pension elusive for Aeta guerrillas

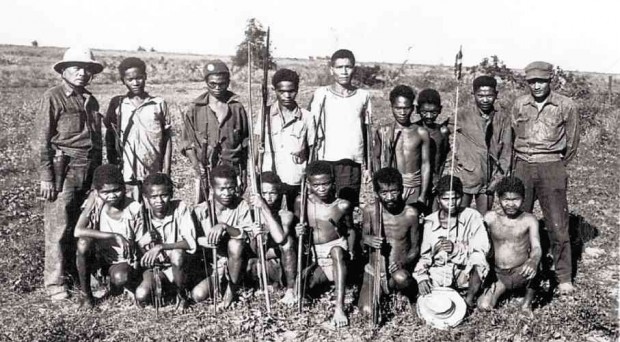

THE AETA SQUADRON 30 (Negrito Special Troops) of the Bruce Guerrilla unit that fought during World War II. The photograph was taken in Bamban, Tarlac province, in 1945. PHOTOS FROM THE BAMBAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY COLLECTION

Sadness, if it can be weighed, was heavy when Emiliano Sanchez spoke of a military pension he has yet to receive or enjoy. Considered to be one of the last three survivors in Aeta Squadron 30 based in Bamban town in Tarlac province, Sanchez said in Kapampangan, “Money has not been released.”

Sanchez said he wanted the Philippine Veterans Affairs Office (PVAO) to recognize him, his brother-in-law Roman Sanchez (Pan Paruman) and Mario Pamintuan (Pan Tulandit) as guerrillas who served in the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) during World War II, and to grant them pensions.

Their names appeared in the roster of the all-Aeta squadron, a list obtained from the US National Archives, according to Rhonie de la Cruz, founder and president of the Bamban Historical Society (BHS).

Professor Joel Regala of Holy Angel University in Angeles City called attention to the plight of the three men who spoke of their status in the course of a history research he has been conducting.

According to De la Cruz, the Aeta Squadron 30 consisted of more than 100 Aetas organized by Capt. Alfred Bruce in the subvillage of Mataba in Barangay Sto. Niño, Bamban, as well as in Flora and Kalangitan at the boundary of Bamban and Capas immediately after the fall of Bataan on April 9, 1942.

Article continues after this advertisementBruce, a member of the Philippine Scouts based in nearby Fort Stotsenburg, the precursor of Clark Air Base, took orders from Lt. Col. Claude Thorpe of the 26th Cavalry, which was based at the fort before the war.

Article continues after this advertisementBruce also led the Bamban Battalion, Capas Battalion, O’ Donnell Regiment and Aeta guerrillas in the Capas-based Binyayan Company that were all under Thorpe’s command in the Luzon Guerrilla Force that countered the Japanese Kembu group, De la Cruz said.

Bruce had command of the South Tarlac Military District, expanding this to the whole of Tarlac after the Japanese captured and killed Thorpe later in 1942.

Emiliano and Roman Sanchez could only say they are in their 90s now. They do not know the exact date of their birth, saying they were young men when Manuel L. Quezon was the Commonwealth President. They refer to that period as “peacetime.”

Claims denied

Jet Fajardo-Rivera, deputy chief of PVAO’s veterans records management division, said the claims of Emiliano and Roman Sanchez had been denied because they failed to establish their identities.

“Their submitted documents were analyzed and matched with the military service records we have obtained from the [Office of the Adjutant General]. It’s true there were Pan Paruman and Emiliano Sanchez who served under Bruce guerrillas but it was established that those applicants were not the same who owned the records,” Rivera told the Inquirer on Monday.

In particular, Rivera said the thumbprints of the two Aetas were “not identical” with those generated in 1946 by a summary court officer who was designated by the Philippine Army to prepare and submit the service records of Filipino guerrillas.

The thumbprints and service records had presumption of regularity, she assured.

It was not known how many Aeta guerrillas in Central Luzon or members of the Aeta Squadron 30 had received pensions. This was because veterans were not classified by tribes or linguistic groups.

The two Aetas have not appealed their cases with the PVAO, Rivera said, adding that no persons have collected pensions through their names or on their behalf.

Emiliano and Roman Sanchez said they were recruited by Pedro Margarito, Emiliano’s uncle who worked as guide to cabalyerya (American troops on horses) who carved paths to a camp in O’ Donnell in Capas.

“We took care of Bruce,” Emiliano said, adding they secured the American and his compatriots in his headquarters in a cave in Bagingan in upper Mataba.

The Japanese failed to locate them even when the Allied Forces recaptured the Philippines in October 1944.

“We also planted rice, yam and sweet potato to sustain Bruce and other fighters,” Emiliano said. “When supply ran out, we raided the sentral for rice,” Roman said, referring to a granary of the Cojuangco family in Bamban.

Emiliano said he also guarded the path leading to the Bagingan cave, instilling discipline among Aetas who he prohibited from making bonfire to prevent being detected by the Japanese.

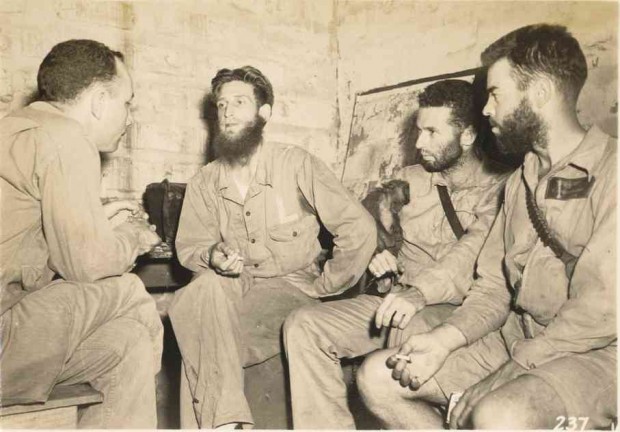

Roman, who is blind now, said the squadron rescued a number of US pilots whose aircraft were downed by Japanese bombers.

SGT. ALFRED D. BRUCE (center) being interviewed by an American intelligence officer. On the right are two naval aviators who were rescued by Aeta Squadron 30 after they were shot down over Clark Field.

Sense of smell

American guerrillas used the Aetas’ strong sense of smell to locate Japanese, Emiliano said, laughing.

Without boasting, they recalled having poisoned around 50 Japanese soldiers who ate bule (red beans). Dead or immobilized, the Japanese were disarmed, their guns snatched.

Emiliano and Roman said they were among the squadron members who marched one night to secure Bruce’s transfer to Barangay Patling in Capas where American soldiers gathered days before the eventual return of Allied Forces.

“Before he left, Captain Bruce told us we would get benefits,” Roman said. In mopping-up operations of Allied Forces, he said their squadron pursued Japanese stragglers who dug hideouts in Bamban mountains.

They had not seen Bruce or heard from him again after they last saw him at the old house of the Aquinos in Concepcion town. They said it was in 1995, or four years after Mt. Pinatubo’s 1991 eruptions, that Baptist pastors began helping Aeta guerrillas claim recognition and pension.

Although their clan has asserted ownership over large tracts of ancestral domain, Emiliano and Roman consider themselves poor and find the process of following up with the PVAO to be costly.

De la Cruz said the plight of the three Aetas brings to fore not only the contribution of these indigenous peoples in the struggle against colonial rule but also the neglect of Aetas who fought in the war.

“They did not know how to write. They do not have birth certificates or cedula as proof of their existence. They live far up in the mountains. These must be the reasons for their difficulties in filing claims for pension,” he said.

The BHS has no registry of Aeta pensioners among recognized guerrillas in Tarlac.

Emiliano and Roman said they wanted to get pension so they could buy some work animals and farm tools for their children to make the lutan tua (ancestral lands) productive.

“There is no anger in us in spite of the neglect. God will take care of us,” Roman said.