Never too young to be heroes

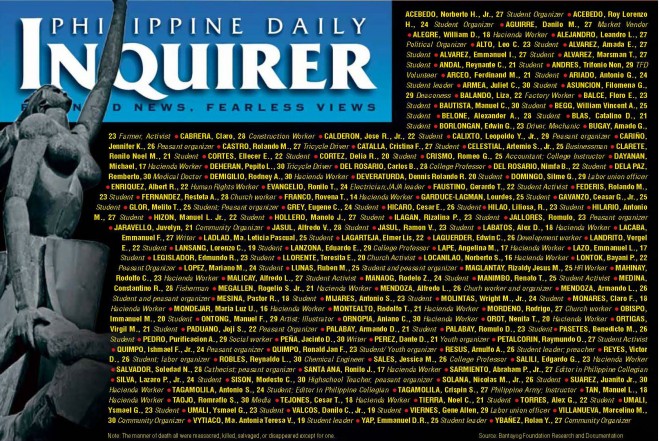

HEROES REMEMBERED Those who died fighting the Marcos dictatorship, their names enshrined in Bantayog ng mga Bayani, will be honored at the National Heroes Day commemoration on Monday.

(First of a series)

The dark days of martial law are past but the ghost of suppression of the truth lives on among cyberhackers who attempt to cast a veil of forgetfulness over the blood of martyrs when they recently hacked the website of Bantayog ng mga Bayani.

Bantayog, a memorial honoring individuals who defied the repressive Marcos regime, has recognized 253 heroes, about half of them young people between 14 and 30 years of age, including 69 students.

Of the 136 young heroes, one died of “natural causes”—Abraham Sarmiento Jr., who died months after being released from solitary confinement in Camp Crame, during which he was deprived of medical attention.

The rest were killed, massacred and tortured. At least 20 simply disappeared.

Article continues after this advertisementData on computers can be stolen or lost, but some truths are so precious they must be safeguarded in the hearts and minds.

Article continues after this advertisementTo forget is to live in a darker world.

The least that can be done for those who sacrificed so much is to keep them alive in our memories. As Bantayog puts it: “In honoring our martyrs, we proclaim our determination to be free forever.”

As the guardians of Bantayog rebuild their website to keep alive the stories of these freedom fighters, Inquirer Research also traces the sacrifice of the young heroes who fought a dictator and laid down their lives so future generations can be free.

A martyr at 14

Fourteen-year-old Rovena Franco is the youngest name on Bantayog’s list. She was the youngest fatality in the Escalante massacre, during which 19 other people age 30 and younger died while staging a protest on Sept. 20, 1985, to commemorate the 13th anniversary of martial law in New Escalante, Negros Occidental.

READ: I saw martial law up close and personal

Rovena had been working at a sugar hacienda since she was 12, stopping her schooling upon reaching Grade 5. Her parents, Bernaldo and Tessi Franco, were also hacienda workers. Rovena was the second offspring in a brood of five.

Rovena, a helper in the home of the owners of Hacienda Rick, was with friends and family during the protest demonstration. She was among those wounded when shooting erupted.

Taken to Foundation Hospital, she bled to death.

Volcano explodes

Rovena’s mother said the hospital doctors were prevented by the military from attending to Rovena.

The province of Negros Occidental, well known as a sugar producer, had been called a “social volcano” waiting to explode as the sugar industry crisis of the 1970s left many farm workers without livelihood.

As the economic gap between the rich and the poor widened, Negros became ripe for a social explosion.

The Escalante massacre, remembered by the town as “Bloody Thursday,” happened during a nationwide “welga ng bayan” (general strike). The three-day strike started on Sept. 19, when thousands of protesters held a vigil in front of the Escalante town hall.

The following day, the protesters filled the streets, surrounded by armed soldiers, policemen and paramilitary forces deployed to disperse the crowd.

Gunfire at noon

Shooting started around noon. First, water cannons were fired; then, tear gas followed. Chants of “Bigas, hindi tear gas!” (Rice, not tear gas!) heightened the tension.

Gunfire erupted at past noon. Many farm workers were instantly killed.

Other victims of the massacre who were also in their teens included Norberto Locanilao, 16; Maria Luz Mondejar, 16; Michael Dayanan, 17; Angelina Lape, 17; Ronilo Santa Ana, 17; William Alegre, 18; Alex Labatos, 18; Claro Monares, 18; Manuel Tan, 18; and Cesar Tejones, 18.

All of them worked in the hacienda, like Rovena.

The other victims were in their 20s, like Nenita Orot (20), Juvelyn Jaravello (21), Rogelio Megallen Jr. (21), Rodolfo Montealto (21), Rodolfo Mahinay (23) and Edgardo Salili (23). They were also hacienda workers, except Juvelyn, who was a community organizer.

First shot

Juvelyn was leading the chanting when the massacre began. She was killed by the first shot that rang out during the protest.

She was the first Escalante martyr recognized by Bantayog in 1992. She and the rest of the Escalante martyrs were also honored as heroes by Bantayog in December 2013.

The town of Escalente has not forgotten the massacre and continues to honor its young martyrs with annual activities. A monument in their memory stands on the same spot where their blood was spilled for democracy.

Wall of Remembrance

The Bantayog ng mga Bayani (Monument of Heroes), located in Quezon City, features a black granite Wall of Remembrance, where the names of those who fought against the Marcos regime are etched.

The wall stands a few meters from a 13.7-meter (45-foot) bronze monument by renowned sculptor Eduardo Castrillo. The monument depicts a defiant mother raising up a fallen son.

The monument, the commemorative wall and other structures at the Bantayog complex are dedicated to the nation’s modern-day martyrs who fought against all odds to help restore freedom, justice, truth and democracy in the country.

The Bantayog complex now includes an auditorium, a library, archives and a museum. Bantayog’s 1.5-hectare property was donated by the administration of Corazon Aquino, through Landbank, the year after the Marcos dictatorship was toppled and Aquino took power in 1986.

Every year, names are added to the Wall of Remembrance. The first 65 names were engraved on the wall in 1992.

Source: Inquirer Archives, Bantayog.org, Bantayog Foundation Research and Documentation

RELATED STORIES

Lawmaker proposes heroes’ cemeteries in provinces