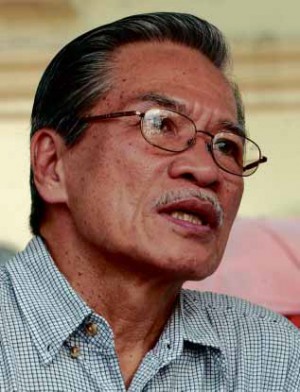

Satur Ocampo: True friends in high places helped me underground

Editor’s Note: Starting Sept. 21, the 42nd anniversary of the proclamation of martial law by President Ferdinand Marcos, we have been running a series of articles to remember one of the darkest chapters in Philippine history. The articles are necessarily commemorations and more so a celebration of and a thanksgiving for the courage of the men and women who endured unspeakable pain and loss to overcome the Marcos dictatorship and regain our freedoms. These are some of their stories.

I’ll cite only five of the friends who have passed away: Joaquin “Chino” P. Roces, Gregorio S. Licaros Sr., Felipe F. Cruz, Mariano V. del Rosario, and Leonardo Bascara. May they rest in peace!

“Living dangerously” is how life in the underground, specifically the revolutionary underground, is often depicted. In my experience under the Marcos dictatorship, yes, it was that but a lot more.

The danger of getting arrested or captured, tortured and detained (or worse, getting summarily killed or “disappearing,” like the numerous martyrs of the struggle) lurked every day and night. In a number of incidents, I eluded such danger.

But on Jan. 14, 1976, it became a reality for me. I was captured, subjected to severe torture and prolonged military detention—nine years, three months.

Article continues after this advertisementBut for over three years before that I was able to move around quite freely, incognito. I drove borrowed vehicles without a driver’s license, took public transport, or walked through crowded streets to duck into private homes or enter business offices to meet with friends. To confer with comrades, I took roundabout routes and observed other security measures.

Article continues after this advertisementLike normal couple

My wife and I performed our tasks in the underground while outwardly appearing to be a normal couple with two small kids. (When I was captured our daughter was aged 3 and our son was 2.)

We lived simply on a limited budget, maybe more abstemiously than ordinary people who were our neighbors. But our little girl relished eating veggies and fish (which she does to this day), with an occasional small piece of meat.

I remember how happily she remarked at supper, “Sarap kangkong! Sarap manok! (Kangkong is good! Chicken is good!) ” while munching on tasty braised adidas (slang for chicken feet).

Friends during martial law

I enjoyed meeting with friends because invariably I came away from our encounters elated by their affirmation of my decision to fight against the dictatorship; and also because most of the time they made my wallet a little fatter, showing their support for the cause, and for me, in more concrete ways.

And who could I rely on to help but friends who had means, with whom I had developed personal and political relationships during the eight years I worked as a journalist with The Manila Times (the largest newspaper in the country before martial law)?

Chino and higher purpose

Chino Roces, the Manila Times publisher, was arrested and detained along with several journalists whose publications were shut down upon the declaration of martial law in September 1972.

In 1969, Chino, who knew of my affiliation with the radical youth organization Kabataang Makabayan (headed by Jose Maria Sison), called me to his office. We talked about KM and the protest actions it spearheaded against the Marcos government. To my surprise, he said he would support KM by pledging a monthly cash contribution (which he fulfilled). That began our secret political relationship.

After his release from military detention, Chino agreed to meet with me alone at his home. It was perilous for both of us to meet there—presumably he was still under surveillance, and I was being actively hunted by the military. But we took the risk for a higher purpose.

‘Carry on’

After our talk, he handed me cash in an envelope, embraced me tightly and encouraged me to carry on.

My capture in 1976 cut off our contact.

We met again sometime after the Ninoy Aquino assassination in August 1983. Having secured a pass as a political detainee, I had a day with my children at my in-laws’ home.

Midafternoon I got a call on the home phone. It was Chino calling from the National Press Club (NPC), inviting me to come over to meet with him and colleagues from the press who had gathered there. My military escorts agreed to let me drop in at the NPC before returning to the Bicutan detention center.

Help from Tony Nieva

As we hugged amid an uproarious crowd, Chino jokingly said, “Satur, you can escape from here, through the window. We’ll cover for you!”

Picking up Chino’s idea, I did escape through the NPC. But not right then. I slipped out of that building back to the underground on May 5, 1985, after voting in the club’s annual election.

I freed myself—with no little help and cooperation from Tony Nieva, the club president then, who convinced Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile to grant me a pass to vote as a lifetime NPC member.

Brandy with Mang Gorio

Gregorio Licaros was the Central Bank (CB) governor from 1970 to 1981. Before that he was the chair of the board of governors of Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP). In both positions, I covered him. I must have won his trust and confidence to the point that, after office hours, he would invite me to his inner sanctum “to unwind.” He did that occasionally as DBP chair but more frequently later as CB governor.

Over snifters of expensive brandy, Licaros (call me “Mang” Gorio, he urged) would update me, off the record, on the true state of the country’s monetary and financial systems. Then he would fall back to his avuncular self, shifting the topic to mundane matters, personal narratives punctuated by thigh-slapping laughter.

He wasn’t impressed by the other Marcos economic managers brandishing their Ph.D.s earned from famous universities abroad. He took pride in doing his job the best way he knew how, from direct experience—and producing positive results. “Kahit accounting graduate lang ako (Even if I am only an accounting graduate)” from a Manila university, he remarked with a glint in his eyes.

Mang Gorio was as generous in extending financial support as he was in expressing genuine respect for my political views. I cherish his commending me for what I was doing in the underground: “It’s for the good of the Filipino people.”

A friend called FF

FF Cruz (as he was popularly known) was a civil and geodetic engineer who founded and ran the highly successful construction-surveying firm bearing his name. Our friendship developed when I was editing the Times construction section in the late 1960s. The friendship grew stronger during the martial law years. He never hesitated to receive me at his office whenever I called. He provided me with funds beyond what I hoped for.

FF and I were both born of peasant families and worked our way through college (he did better because he earned two engineering degrees, while I got none). After his business success, he paid back his home village by constructing an entire school building, establishing a foundation granting scholarships to poor youths, and building a church.

There was something else about FF. In one of my visits, he handed me three books, including Lenin’s classic, “Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.” He had been to China, bought the books there. He said he had read them all and wished others would do the same. Since I already had a copy, I passed it on to another friend, the economist Alejandro “Ding” Lichauco, who was quite appreciative of Lenin’s seminal work after going through it.

Meeting Marianing

Mariano V. del Rosario I met when he was a director of the Philippine Chamber of Industries in the 1960s. He was into import-substitution manufacturing.

Along with other struggling Filipino entrepreneurs then—alas, many of them subsequently sidelined or forced to shut down by unrestricted importations and foreign competition—he shared my enthusiasm for national industrialization. How he loved discussing the issue, expressing nationalist views critical of the government’s proforeign economic policies and programs.

Like Mang Gorio, Marianing (his preferred nickname) was a genial, accommodating friend. He was forthright, aboveboard. Meeting with me at his factory office, he told me how concerned he had been about regularly seeing me and financially supporting my underground activities. So he consulted the former Sen. Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo, who was known for his strongly anticommunist sentiments.

With a wink and a smile, Marianing disclosed, “I informed Soc, as my lawyer, about your coming here. He advised, ‘Satur is a communist, but a good man. Help him!’”

Refuge under Panther

It was altogether a different experience relating to Dr. Leonardo Bascara, a prominent psychiatrist whose sartorially avant-garde color combinations were weird by the standards then but became in vogue later. He was introduced to me by a friend, shortly after I had gone underground, as a “reliable ally.” I trusted my friend’s word and she proved to be right.

Bascara, who chose the alias “Panther” for himself, provided me with an ever-ready refuge in his clinic right inside his residence in an upscale subdivision. He also made his motor pool accessible, providing me transport whenever I needed a car to drive to wherever I needed to go, no questions asked.

In one instance the only car available, just when I urgently needed one, was a dune buggy—a bright green two-seater, open-top, low-slung vehicle with big tires. I had to use it to catch an important meeting. Once I started the engine, and whenever I pressed my foot on the accelerator, the buggy’s exhaust pipe emitted a loud vroom. Cruising speed was marked by sharp, staccato sounds.

Attention-grabbing

I didn’t mind the people curiously looking at me drive by in a queer-looking car making that much noise on the road. But when I got to the place where I was to meet comrades belonging to another underground unit, they were aghast at seeing me arrive in such an attention-grabbing way.

But no untoward incident happened. Everything went just fine that day and thereafter. I accomplished my mission. I returned the buggy and cheerily thanked Panther for an exciting drive.

RELATED STORIES

Marcos based martial law declaration on lies—Satur Ocampo