Photographs and memories by Ed Santiago, photojournalist

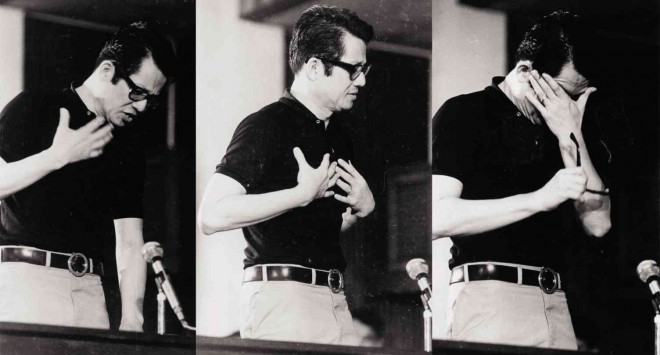

THE TRIAL Aug. 27, 1973, Fort Bonifacio. Sen. Benigno Aquino “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. challenged the jurisdiction and independence of the military commission of Marcos-appointed generals and colonels. He refused to participate in the trial. On Nov. 25, 1977, the military tribunal sentenced him to die by musketry. PHOTOS BY ED SANTIAGO

MANILA, Philippines—For 41 years, photographs on this page were stashed in a sealed envelope that occupied a place of honor among his “chaotic” files—a vast collection of black-and-whites, his life’s work.

“I should start seriously organizing these files,” veteran photojournalist Edgardo “Ed” Santiago said. “I’m 79; there are many things I wouldn’t remember if not for my pictures. I consult them; they talk to me.”

The first day in Ninoy Aquino’s trial by a military court is among the other “things,” he wouldn’t forget. He didn’t even listen to the proceedings, he admitted; he couldn’t help tuning in to what had been unspoken.

From Ninoy’s evident agitation, Ed sensed how intense the questioning was. “Intense. He was driven to tears.”

‘Dead man walking’

Article continues after this advertisementHe recalled becoming increasingly certain that his subject was a dead man walking. It was August 1973. “I realized they would kill him.”

Article continues after this advertisementFrom that moment on, he could see only the main characters in the unfolding scene: the prosecutors, the accused, the weary family.

Ed, already an awarded photo essayist at the time, had found his “story”—Ninoy this close to crumbling, the wife stoic, their youngest daughter mercifully spared the sense of foreboding—but felt in his gut that it could not be told anytime soon.

Dangerous time

Back at work, no one asked Ed for photographs of the coverage, and he wasn’t surprised. “I had known that beforehand, but I still went to cover because it was my assignment; also, because it was clearly bound to be a page in our history.”

He processed the negatives and printed the pictures himself, then brought them home. “I was right to do that,” he said. True enough, when the Daily Express shut down in January 1987, heaps of negatives were left behind. “Many pictures about martial law were destroyed.”

Everything of his that he felt important, Ed saved “for when the right time came.” Meanwhile, he avoided talking about the pictures from that trial. “A few colleagues asked for prints; I gave away one or two, and a few portraits. Everything else, I kept. I had little choice; it was a dangerous time.”

THAT’S WHAT FRIENDS ARE FOR Ninoy is shown with fellow members of the Liberal Party Jovito Salonga and Gerry Roxas.

Originals

Before Ed’s visit to the Inquirer three weeks ago, he had long planned to entrust the pictures to editor in chief Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc. The prints he presented to the editors were remarkably clear and sharp. “Originals,” he told his promptly engaged audience. “No one else had seen these until now.”

Let alone their mint condition, he was proud of the photos’ integrity. “Negatives don’t lie,” he said. He had shot the trial proceedings in color as well but, he insisted, some narratives just naturally lent themselves to black-and-whites.

This headstrong veteran of five daily broadsheets has yet to cross over to digital photography. He has kept three beloved Nikon Fs, an enlarger and several lenses, even if they’re stuck up. “They no longer move.”

That trial was not his first, or last, encounter with Ninoy. “I used to cover President Marcos’ trips abroad as part of the official entourage,” Ed said. “I chanced upon Ninoy on one of those trips, in Washington, DC. He and (newspaper columnist) Teodoro Valencia were friends. I have shots of him being interviewed there by The Associated Press. It looked serious. I was shooting through a glass window from outside the hotel.”

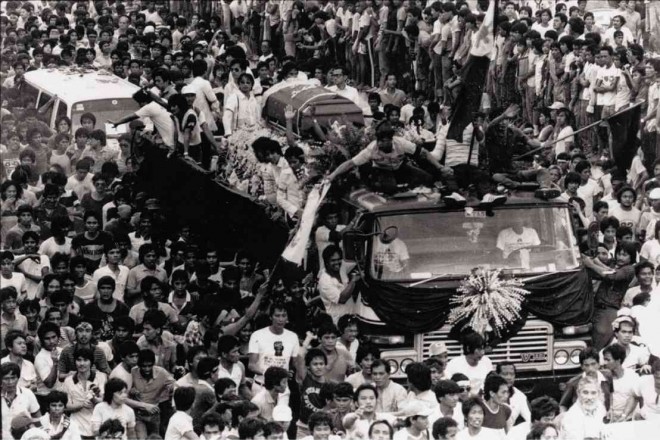

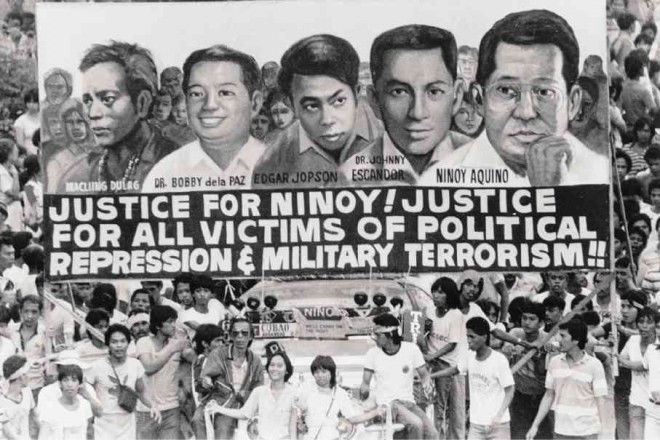

On Aug. 31, 1983, Ed covered Ninoy’s funeral procession from a building on Roxas Boulevard. This one was not an assignment. “I should be part of my country’s history. My grandchildren know I am a photojournalist. I should be able to tell them what happened in my time, through my pictures.”

Part of the funeral cortege found its way to the Aquino Museum in Hacienda Luisita, a friend told Ed. “I haven’t gone there to check,” he said. “It might hurt to look.” But that’s just because, he jested, “My friend said it was cropped (pointed to the lower part) here.” Seriously, what he told his friend was, “I’ll first have it published in the Inquirer. Then we can go.

Attention: Jaime Zobel

In several other sealed envelopes at home, Ed keeps a few more visual history capsules waiting for the right time and platform. A set from the day that journalists, arrested at the onset of martial law, were released? “I’d like to show them to Jaime Zobel de Ayala and maybe exhibit them in his gallery. His appreciation would mean much to me because he’s a photographer, too.”

And that would be his most preferred addition to a long list of solo and group exhibits he has held or joined, here and abroad (Nauru, Japan, Holland).

Ed is content for the most part. His two sons (out of seven children) are professional photographers. He has ventured into art photography (“distortion, abstraction”) and, though he has found some joy in color, is happy to have also found a camera shop in Makati that still offers black-and-white negative processing. He gets his R&R every six months in the United States, where a sibling resides.

Now, if he could only organize those files.

Value of preservation

“My father, Manuel Ma. Santiago, was a science illustrator who worked at the National Museum,” Ed said. “He taught me the value of preservation and I should honor that.”

Manuel also bought his son’s first camera. Ed likes telling this story: “I took up fine arts at the University of Santo Tomas. One of my professors, Vicente Manansala (who would be National Artist) told my father, ‘Your son can’t paint but he sees things that no one else does. Get him a camera.’”

His hair all white, Ed still goes around in Levi’s 501 jeans but now wears what he calls “proper” shirts (cotton, button-down) more often than his trademark work tops, sleeveless white tanks. “Give me a press ID,” he joked, “and I’ll shed 50 years right before your eyes.”

RELATED STORIES