US man behind film denies probation violations

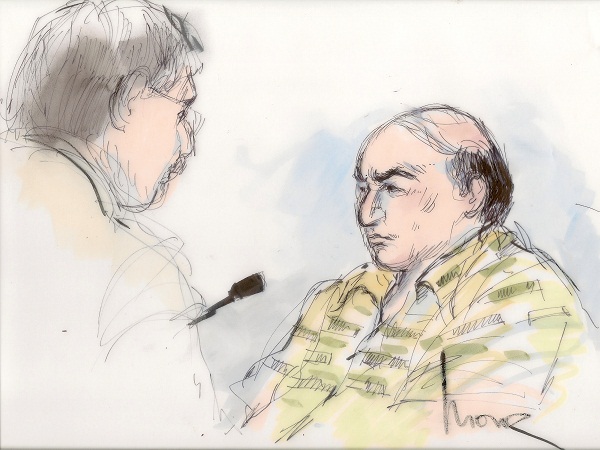

This September 27, 2012, file courtroom sketch shows Mark Basseley Youssef, right, talking with his attorney Steven Seiden in court. Youssef, who was behind an anti-Muslim film that sparked violence in the Middle East, is expected to be asked by a judge Wednesday, October 10, 2012, whether he violated his probation for a 2010 bank fraud conviction. AP/Mona Shafer Edwards

LOS ANGELES — The man behind the anti-Muslim film that sparked violence in the Middle East denied Wednesday that he violated terms of his probation for a 2010 bank fraud conviction by using aliases and lying about his role in the movie.

Mark Basseley Youssef, 55, made a brief appearance in a courtroom packed with media and quietly repeated “deny” when all eight probation violation allegations were read by U.S. District Judge Christina Snyder, who scheduled an evidentiary hearing for Nov. 9.

None of the alleged violations have to do with the content of the movie or whether Youssef was the one who posted to YouTube the 14-minute trailer for “Innocence of Muslims,” which depicts Mohammad as a religious fraud, womanizer and pedophile. Federal authorities are seeking two years in prison for Youssef, who remains in custody and held without bail.

Youssef fled his home in the Los Angeles suburb of Cerritos and went into hiding when violence erupted in Egypt on Sept. 11. The violence spread, killing dozens, and enraged Muslims have demanded severe punishment for Youssef, with a Pakistani cabinet minister offering $100,000 to anyone who kills him.

“My client was not the cause of the violence in the Middle East,” attorney Steven Seiden said after the hearing. “Clearly, it was pre-planned and it was just an excuse and a trigger point to have more violence.”

Article continues after this advertisementThe First Amendment offers broad protections for filmmaking and other forms of expression. Jody Armour, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Gould School of Law, said he is troubled that the government went after Youssef only after the movie caused outrage in the Middle East.

Article continues after this advertisement“They are saying we aren’t going after him on the content, but the reason you are zeroing in on this other behavior is because he was somebody who published a film that caused a violent reaction in another part of the world,” Armour said. “That’s why there’s almost this kind of a dog-whistle quality by this maneuver by the government.”

Federal prosecutors did not comment after the hearing.

Youssef was convicted of bank fraud in 2010 and sentenced to 21 months in prison. Authorities said Youssef used more than a dozen aliases and opened about 60 bank accounts and had more than 600 credit and debit cards to conduct the check fraud scheme.

After Youssef was freed, he was barred from using computers or the Internet for five years without approval from his probation officer. He also wasn’t supposed to use any name other than his true legal name without the prior written approval of his probation officer.

At least three names have been associated with Youssef since the film trailer surfaced — Sam Bacile, Nakoula Basseley Nakoula and Youssef. Bacile was the name attached to the YouTube account that posted the video

Court documents show Youssef legally changed his name from Nakoula in 2002, though when he was tried he identified himself as Nakoula. He wanted the name change because he believed Nakoula sounded like a girl’s name, according to court documents.

Among the violations Youssef denied Wednesday were using “Nakoula” as his name throughout his bank fraud case, obtaining a fraudulent California driver’s license and telling federal authorities that his role in the film was limited to writing the script. Prosecutors have previously said there is evidence showing Youssef had a larger role in the film, but they declined to elaborate.

Seiden explained that Youssef denied all allegations on procedural grounds.

“People go to court all the time and plead not guilty and then later on things transpire in the case as things are known,” Seiden said when asked why his client denied he changed his name. “We’ll see how this plays out on Nov. 9.”

Prosecutors recently sought transcripts from a pair of 2009 hearings in the bank fraud case where Youssef told two judges that his true name was Nakoula Basseley Nakoula. Legal experts said giving a false name to a judge could spell trouble for Youssef on the probation violation allegations and result in new charges since he made the statement about his name before he was sentenced.

“If he was under oath when he lied about his name, it’s perjury,” said Lawrence Rosenthal, a constitutional and criminal law professor at Chapman University School of Law. “If he was not under oath but if giving the false name somehow was going to interfere with the effective administration of justice,” then it would also be a crime.