Food fraud: When what you eat isn’t what it’s supposed to be

MANILA, Philippines—Appearances can be deceiving, and as it turns out, even food sold in markets might not be what you think it is or what their labels and brands dictate.

Across the globe, there are food products that are intentionally altered, misrepresented, mislabeled, substituted, or tampered with and are being illegally sold in markets. Unfortunately, these will reach consumers and cause serious health issues and even death.

These food products, according to the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC)—a body established by the Food and Drugs Administration of the United Nations (FAO) that upholds international food standards—are called food fraud.

“Fraudulent and intentional substitution, dilution or addition to a raw material or food product, or misrepresentation of the material or product for financial gain (by increasing its apparent value or reducing its cost of production) or to cause harm to others (by malicious contamination), is ‘food fraud’,” the Food Safety Net Services (FSNS) explained.

Biggest food fraud scandal

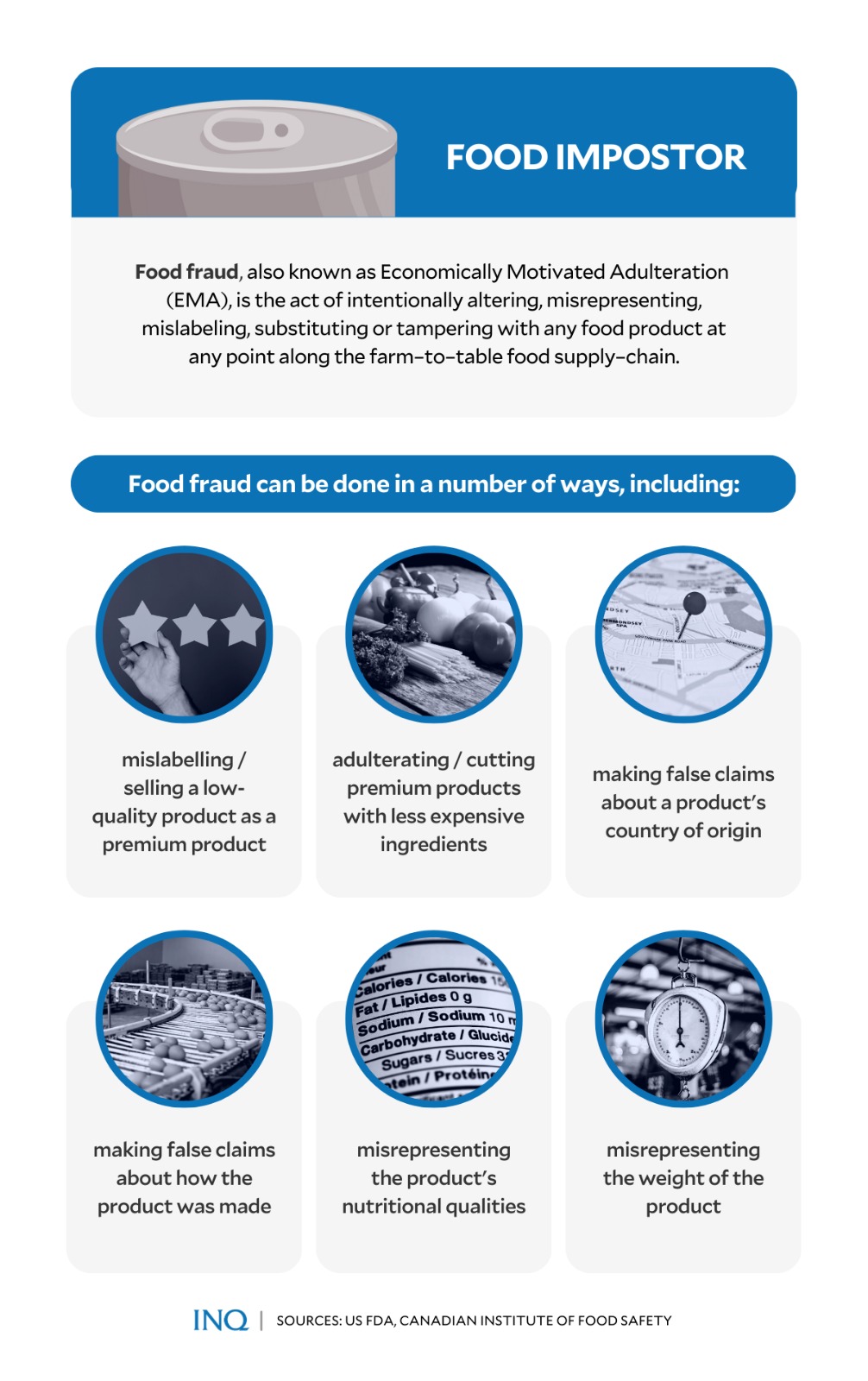

The Canadian Institute of Food Safety has identified the many ways food fraud can deceive consumers, which include:

Article continues after this advertisement- mislabelling or selling a low-quality product as a premium product

- adulterating or cutting premium products with less expensive ingredients

- making false claims about a product’s country of origin

- making false claims about how the product was made

- misrepresenting the product’s nutritional qualities

- misrepresenting the weight of the product

Intentional adulteration of food also involves using unapproved enhancements or additives and purposely contaminating food with different chemicals, biological agents, or other substances.

Article continues after this advertisementThese food fraud methods have notoriously made people very sick and have caused hundreds of deaths.

Among the most significant cases of food fraud recorded took place in 1981 when counterfeit oil caused an outbreak of a condition, known as toxic oil syndrome, across Spain. The oil, fraudulently sold as olive oil, contained rapeseed cooking oil and 2 percent aniline (phenylamine)—a substance originally intended for industrial use.

These caused over 20,000 exposed and clinically diagnosed individuals to experience symptoms ranging from lung failure and limb deformation to the destruction of the body’s immune system.

Over 10,000 were hospitalized, more than 300 victims died, and many survivors were left disabled for life.

Another food fraud case that caused huge damage occurred in 2008 when 300,000 infants in China, who had been fed the same milk formula, were diagnosed with kidney stones. Unfortunately, six children lost their lives due to fraudulent milk.

Investigation and tests revealed that the milk formula ingested by the infants were contaminated with an industrial compound called melamine—which causes reproductive damage, bladder or kidney stones, and bladder cancer when consumed.

Recent cases of food fraud include:

- the European horse meat issue in 2013

- the 2016 tomato scandal in Mexico

- the fake kosher cheese issue in 2017

Food fraud in PH

Instances of food fraud have also been recorded in the Philippines.

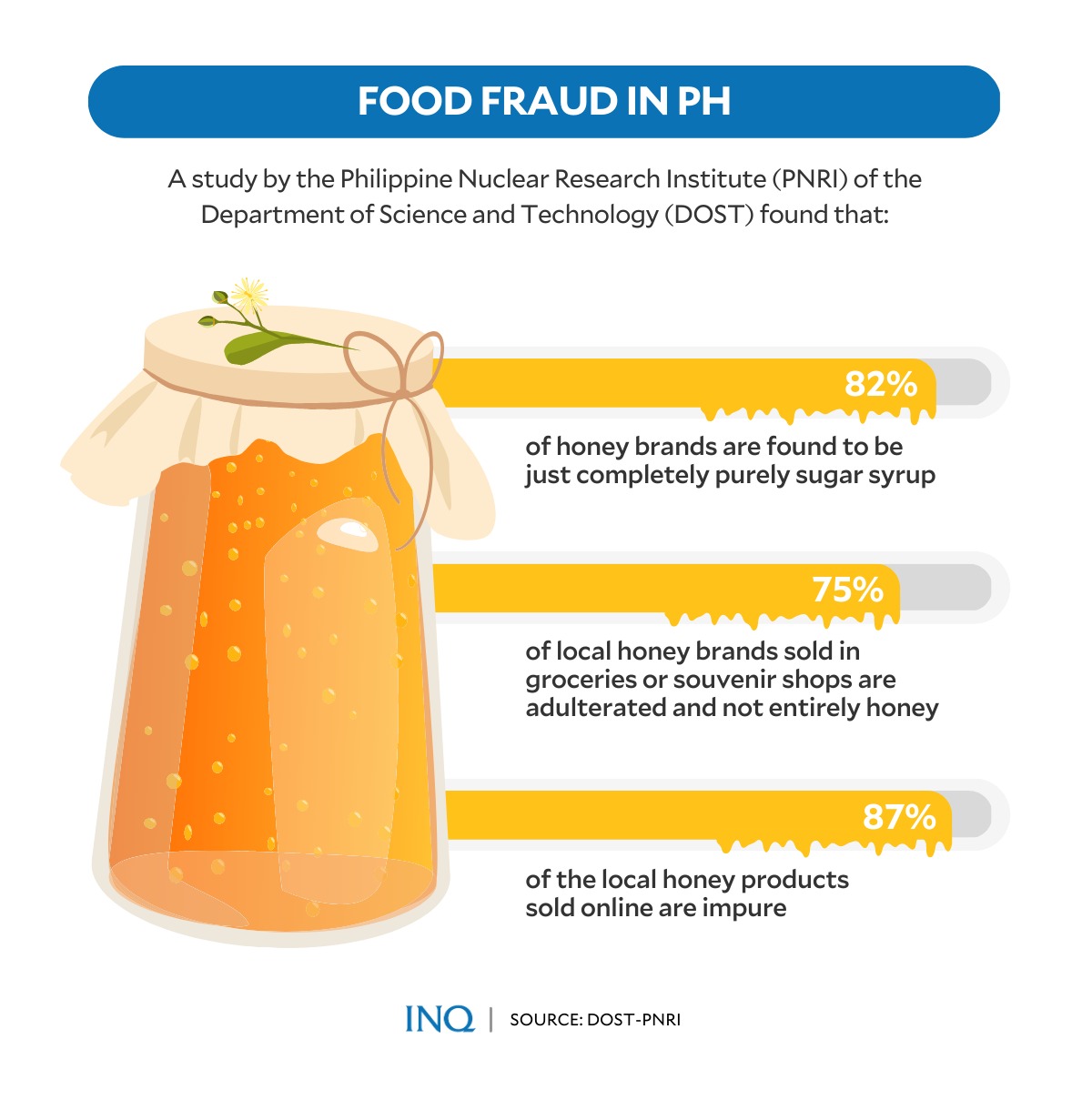

In a 2020 study, researchers from the Department of Science and Technology-Philippine Nuclear Research Institute (DOST-PNRI) discovered that many honey products sold in groceries, souvenir shops, and online platforms were not pure honey.

Based on the results of nuclear-based tests, the study found that many honey products contain syrups made from sugar cane and corn. This fraudulent practice, according to DOST-PRNI, allows manufacturers to increase the volume of their products while reducing production costs.

Dr. Angel T. Bautista VII, DOST-PNRI chemist and head study researcher, said 62 out of 76 honey brands (82 percent) were tested and found to adulterated and composed of 95 percent C-4 sugar syrup.

“So, they are not actually adulterated, but they are just purely sugar syrup,” Bautista said.

The researchers also found that 12 out of 16—or 75 percent—of local honey brands sold either in groceries or souvenir shops were only partially honey. At least 87 percent—or 64 out of 74—local honey products sold online were impure.

In comparison, none of the 41 imported honey products marketed in local stores and tested during the study were found to be adulterated.

“The problem is that people are being tricked,” Bautista said.

“You may be buying honey for its wonderful health benefits, but because of adulteration, you may actually just be buying pure sugar syrup. Consuming too much pure sugar syrup can lead to harmful health effects,” he added.

Honey sold in the market, according to the Philippine National Standard for Honey of the Bureau of Agriculture and Fisheries Standards, must not include any food additives and other substances.

Any substance added to the mixture must be declared in the labeling. It is also required that the label include the geographical location where the honey was obtained.

More than a health issue

Aside from serious health implications, food fraud also has a significant economic impact.

According to DOST-PNRI, impure honey sold in the Philippines can damage the local industry and pull down the price of honey. Fake honey, researchers said, can be sold for as low as one-third of the original price of authentic honey.

“Imagine, incomes that are supposed to be for our honest beekeepers and honey producers are being lost instead due to adulteration and fraud,” Bautista said.

“This is affecting our local honey industry so badly that we estimate that they are losing PhP200 million per year,” he said.

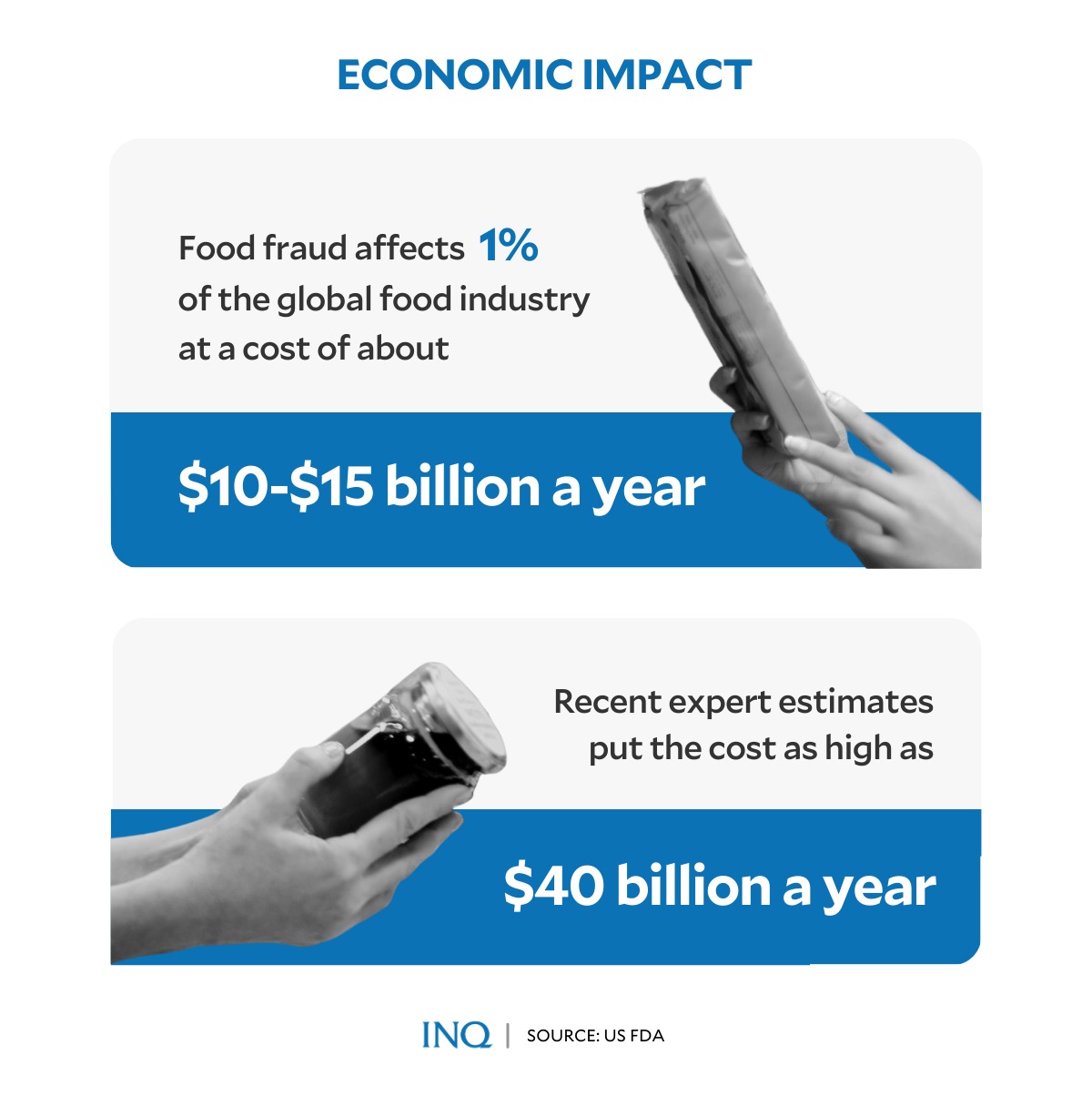

Data by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stated that food fraud affects 1 percent of the global food industry at the cost of about $10-$15 billion annually.

Latest estimates, however, put the cost as high as $40 billion a year.

Unfortunately, while food fraud is not a new problem, experts raised concerns as it has increasingly attracted major attention.

“Food fraud is not a new phenomenon, but it is becoming more sophisticated. It is a complex, global, and critically important issue,” said Nicola Hinder, chair of the Codex Committee on Food Import and Export Inspection and Certification Systems (CCFICS).

Still, there are many ways to prevent damage caused by food fraud and ensure that the food consumers purchase and eat is the food declared on the label and is safe to eat.

In the Philippines, Section 8 of Republic Act No. 10611, or the Food Safety Act of 2013, focuses on the protection of consumer interest, which should be geared toward the following:

- “Prevention of adulteration, misbranding, fraudulent practices and other practices which mislead the consumer”

- “Prevention of misrepresentation in the labelling and false advertising in the presentation of food, including their shape, appearance or packaging, the packaging materials used, the manner in which they are arranged, the setting in which they are displayed, and the product description including the information which is made available about them through whatever medium.”

The punishment and penalties for violating any of the provisions in RA 10611 include fines ranging from P50,000 to P300,000 and imprisonment of up to six years.