Migrant workers denounce ‘modern-day slavery’ in Korea

SEOUL — The Employment Permit System is supposed to be a win-win solution for South Korean employers struggling to find workers and Asian workers seeking higher-paying jobs overseas.

The 16-year-old system, however, is criticized for creating an uneven playing field for migrant workers, making them vulnerable to abusive practices and even “slave-like” exploitation by employers.

At the center of the dispute is a clause in the legislation that effectively bans workers from changing workplaces.

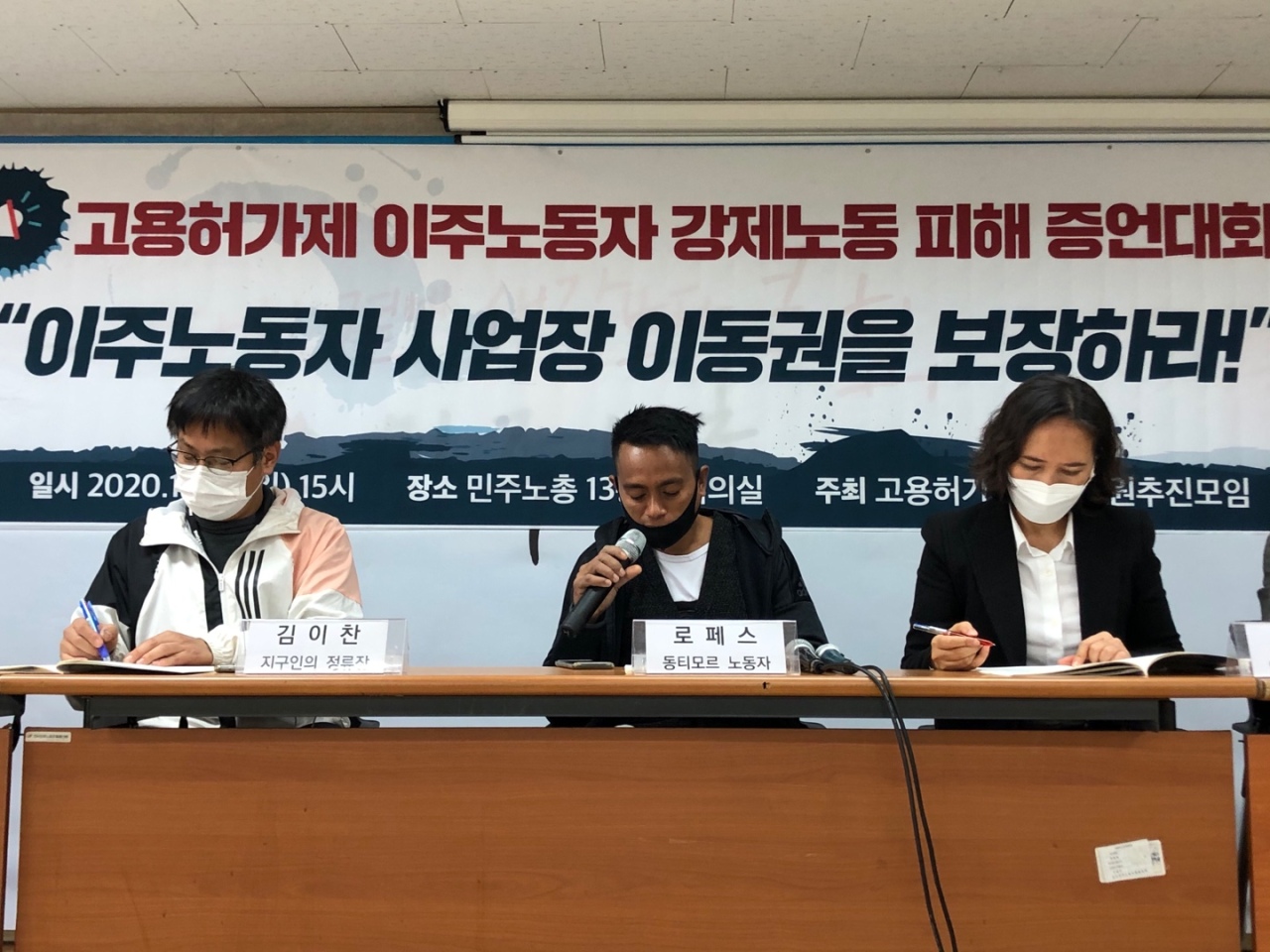

Migrant workers attend a press conference on the plight they face in Korea, in central Seoul on Sunday. (Yonhap) via The Korea Herald

‘Modern-day slaves’

A migrant fisherman from Timor-Leste, who wanted to be identified only as Lopes M., endured appalling working conditions and human rights violations on a small island for years.

“During anchovy season, I even went to sea twice a day, had to dry anchovy and take care of fishing nets as well, working for about 15 to 20 hours a day. That didn’t mean I made more money,” Lopes M. said in fluent Korean at a press conference in Seoul on Sunday.

He was virtually locked up and isolated on Gaeyado, off the coast of Gunsan, as he was not allowed to leave without permission from his employer. He was dispatched to other workplaces several times, in breach of his employment contract. He earned about 2 million won ($1,765) per month, which he found out only recently because his employer had kept his bankbook.

Article continues after this advertisement“While fishing on the boat, no meal was provided, but only bread and Choco Pie,” he said, referring to a brand of chocolate cake snack.

Article continues after this advertisementLopes M. first came to Korea in July 2014 and worked for his boss on Gaeyado for four years and 10 months. He got a second work permit in 2019, valid for another four years and 10 months, on the condition that he stay with the same employer.

He escaped from the island in September this year and has been staying at a shelter ever since.

“If I could, I would like to change my workplace and go to Jeju Island, where my friend is,” he said.

The predicament facing Lopes M. is not an isolated one.

In July, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea conducted an inspection into the working conditions of 63 migrant fishing crew members on islands off the west coast and found they clocked 12 hours a day on average with less than an hour for breaks.

Some 90 percent of the workers said they’d had no official days off for a year. Their average monthly income was about 1.87 million won, much lower than the monthly minimum wage of 3.08 million won. There were six cases where migrant workers had their passports confiscated and 23 where their bankbooks were taken away.

A migrant fisherman from Timor-Leste, who wanted to be identified only as Lopes M., speaks about his experience of working long hours without being paid properly at a press conference in central Seoul, Sunday. (Ock Hyun-ju/The Korea Herald)

Tied to employers by contract, visa

A Vietnamese national who began working in Korea in June 2019 developed nasal symptoms after prolonged exposure to welding fumes and gases. When he told his employer about it in January, his boss promised to let him change his workplace if he stayed for another six months.

He asked again after six months, only to be refused, blackmailed, assaulted and even accused of carrying the coronavirus.

“After I completed working for a full year on June 19, I asked the boss again whether I could find another employer. The boss rejected it,” said the man, who wanted to be identified only as An. He said his employer forced him to sign a paper agreeing to work there for another three years.

“On July 13, my employer took my temperature and took me to

a health clinic for a coronavirus test, even though I had no symptoms,” An said, adding that he was isolated for two weeks in July in a small room without a bed or bathroom.

After his boss assaulted him in early September, he reported it to the police and filed a petition with a local employment center requesting permission to change his workplace. He is currently awaiting the center’s decision.

Shiva Tharu, a 40-year-old man from Nepal, also asked his employer to end his employment contract and allow him to transfer to another workplace last year after struggling under a heavy workload.

“My boss said he would allow it only if I paid him,” said Tharu. He gave his boss 500,000 won and was finally set free from the contract with a clothing factory. He now works at a metal factory.

Shiva Tharu, a 40-year-old man from Nepal, poses for a picture after an interview with The Korea Herald, Sunday. (Ock Hyun-ju/The Korea Herald)

Calls for an EPS overhaul

Launched in 2004, the employment permit system has been a major platform to import foreign workers from 16 Asian countries to meet labor shortages at small and medium-sized firms in the manufacturing, agricultural and fishing sectors. Those low-skilled jobs are often shunned by Korean workers for their poor working conditions and low pay. Currently, there are about 248,000 migrant workers here under the EPS.

Migrant workers arrive in Korea with a contract, which initially allows them to work for up to three years. If their employers agree, they can extend the contract by a year and 10 months. If they are considered “diligent workers,” they can earn a chance to reenter the country and work here for another four years and 10 months.

They are only allowed to change workplaces up to three times during their stay, and only in exceptional cases. With an employer’s consent, a worker can end a contract and transfer elsewhere. Otherwise, workers must show evidence that they have been mistreated or underpaid, or their existing workplaces must be shutting down.

Those who leave their jobs without their employers’ consent are reported to the police as illegal immigrants and could end up being deported, activists say.

Jeong Jina, a lawyer at Law Office Be Life, says the EPS infringes on workers’ basic rights.

“The EPS is designed for a migrant worker to work up to nine years and eight months for one employer. A migrant worker signs an employment contract before they enter the country and before they even meet their employer based on limited information on the contract,” she pointed out.

The system is designed only for the government’s convenience — to manage migrants and to meet the demands of employers, she said.

“It does not reflect the human rights of migrant workers,” said Jeong, who is representing five migrant workers who filed a petition with the Constitutional Court in March. In the appeal, the workers argue that the EPS clause restricting migrant workers from changing their workplaces violates basic rights guaranteed by the country’s Constitution and amounts to forced labor.

The Ministry of Labor and Employment, for its part, argues that the controversial restrictions are necessary to prevent the system from turning into a route of illegal immigration.

The main goal of the EPS is to curb the shortage of workers for small and medium-sized employers here, and migrant workers can enter Korea only when there is an employer to hire them, the ministry says.

Woo Sam-yeol, director of the Asan Migrant Workers Center, said it is time that Korea face up to the inhumane treatment of its migrant laborers. “We cannot deny migrants are tied to their employers, with their conditions similar to those of slaves,” he said.

Foreigner or not, no one should fall victim to forced labor, and everybody deserves to get paid fairly for their labor, he added.

Along with the fight at the Constitutional Court, migrant workers and their advocates are mounting a campaign calling for the overhaul of the work permit system.

“Any laborer has freedom to choose and change a job. But for migrant workers, government is not recognizing these basic rights,” said Udaya Rai, head of the Migrants Trade Union. “That’s why appalling working conditions where migrant workers have been forced to work are not improving.”

The migrant workers’ groups are running a petition campaign and are also set to hold up a placard demanding the abolishment of the EPS at 2 p.m. Sunday at Gwanghwamun Square in central Seoul. Similar rallies are scheduled to take place every third Sunday starting in November.