Sudan’s bid to ban genital mutilation sparks hope, caution

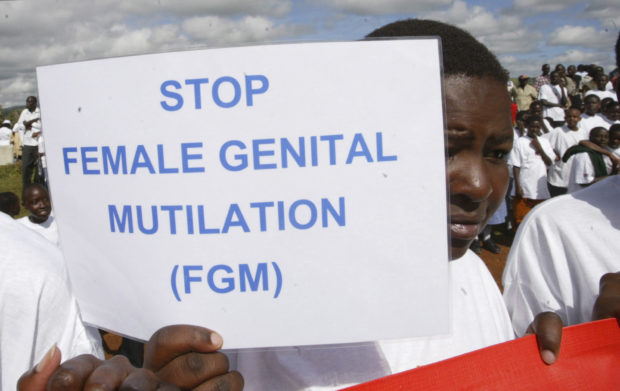

In this April 21, 2007 file photo, a Masai girl holds a protest sign during the anti-female genital mutilation (FGM) protest in Kilgoris, Kenya. The World Health Organization says the practice constitutes an “extreme form of discrimination” against women. Nearly always carried out on minors, it can result in excessive bleeding and death or cause problems including infections, complications in childbirth, and depression. (AP Photo/Sayyid Azim, File)

CAIRO — It’s been more than 60 years. But the scene is seared still into Kawthar Ali’s mind. Women pinned her down on a bed. She was maybe 5 1/2 or 6 years old. Holding her knees, they spread her legs open, her genitals exposed.

At the time, she didn’t fully understand what followed. But that day Ali joined the many Sudanese girls who had undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), a practice that involves partial or total removal of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons.

“It’s the one incident that has affected my life the most,” said Ali. “It feels shameful for people to expose your body and do this to you, like a rape.”

The anguish unleashed that day led to an unwavering conviction: No daughter of hers should ever endure that pain. That decision pitted Ali against her own mother and a society where nearly 87% of women between 15 and 49 years old are estimated to have undergone a form of FGM, according to a U.N.-backed 2014 survey.

Soon, Ali and others like her might have the law on their side. Sudan’s transitional authorities are expected to outlaw the procedure and set punishments of up to three years in prison and fines for those who carry out FGM, according to a draft bill obtained by The Associated Press. The Cabinet has approved a set of amendments that includes criminalizing FGM. Procedures to pass the law are expected to be completed, by the sovereign council and council of ministers, in the coming few days, Minister of Justice NasrEdeen Abdulbari said in a statement sent in response to AP questions.

Article continues after this advertisement“I’m very excited, very proud,” said Nimco Ali, co-founder of The Five Foundation, which works to end FGM. “Those are the kind of things that we need to be celebrating because that was a part of democracy coming to Sudan.”

Article continues after this advertisementAlthough she lauds the move, Kawthar Ali is not celebrating yet. “This thing will die very slowly,” she said of FGM. “It’s an issue related to our traditions and the Sudanese culture.”

Like many in Sudan, Ali was subjected to an extreme form of FGM known as infibulation, which involves the cutting and repositioning of the labia, sometimes through stitching, to narrow the vaginal opening.

The World Health Organization says FGM constitutes an “extreme form of discrimination” against women. Nearly always carried out on minors, it can result in excessive bleeding and death or cause problems including infections, complications in childbirth, and depression.

Millions of girls and women have been cut in countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Reasons differ. Many believe it keeps women clean and protects their chastity by controlling sexual desire. The opinions of religious leaders run the spectrum. Some condone the practice, others work to eliminate it, and others consider it irrelevant to religion.

Mohammed Hashim al-Hakim, a Sudanese Muslim cleric who opposes FGM, said religious leaders must confront attempts to put a veneer of religion on a custom largely rooted in culture.

The practice, he said, predates Islam and crosses religious lines. “No one in their right mind can say that a harmful practice … belongs to religion.”

Under the rule of longtime autocrat Omar al-Bashir, who was ousted in April last year, some Sudanese clerics said forms of FGM were religiously allowed, arguing that the only debate was over whether it was required or not.

It was fear of what people would say, rather than religious beliefs, that led Kawthar Ali’s mother to fight her decision not to subject her own daughter to FGM. Ali even feared her mother would have someone commit it to her daughter while she was at work. She armed her child with a plan: Run to a nearby police station.

In this Oct. 13, 2015 file photo, women from Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi participate in the World March of Woman in Nairobi, Kenya. The World Health Organization says the practice constitutes an “extreme form of discrimination” against women. Nearly always carried out on minors, it can result in excessive bleeding and death or cause problems including infections, complications in childbirth, and depression. (AP Photo/Khalil Senosi, File)

Now 35, the daughter wonders if the police would have helped. She said she is grateful for her mother’s battle. Among high school classmates, she was “the abnormal one” for not getting cut. A rights defender, she spoke on condition she not be identified by name because of the sensitivity of her work.

The practice of FGM, she argued, is interwoven with a patriarchal mentality that connects a man’s sexual pleasure to a woman’s pain and exerts control over women.

“Customs, traditions, and culture are much stronger than written laws,” she said, adding that anti-FGM campaigners need to engage men more.

Neighboring Egypt shows how difficult it is to end the practice. Egypt banned FGM in 2008 and elevated it to a felony in 2016, allowing tougher penalties. Some of Egypt’s top Islamic authorities have said FGM is forbidden.

Still, a 2015 government survey found that 87% of Egyptian women between the ages of 15 and 49 had undergone FGM, though the rate among teens did fall 11 percentage points from a 2008 survey.

Reda el-Danbouki, executive director of the Women’s Centre for Guidance and Legal Awareness, said there have been cases where judges handed down minimum sentences on doctors who broke the law, giving the impression doctors can keep doing so with impunity.

As Sudan’s law is implemented, there is the risk that FGM will go underground, said Othman Sheiba, secretary-general of Sudan’s National Council for Child Welfare. But criminalization sends a strong message, he said: “The government of the revolution will not accept this harm to girls.”

Women were at the forefront of the protests against al-Bashir. Transitional authorities have since taken steps to roll back his legacy, which activists say disenfranchised women in particular.

For FGM truly to end, women must be empowered, Nimco Ali said.

“You bring in the legislation and then you start having the conversation and then real change happens.”

A more “awoken” generation of young Sudanese rejects the practice and wants equality, she said.

A British activist of Somali origin, 37-year-old Ali underwent FGM in Djibouti at age 7. She remembers feeling angry. A severe kidney infection — a complication from the procedure — almost killed her at 11, she said.

“I lost the concept of innocence,” she said. “I felt so broken and so alone.”

For her own procedure, Kawthar Ali was dolled up “like a bride.” Her body was rubbed with oil and she wore a new dress and gold bracelets.

Although she had anesthesia, she remembers the cries of a relative who did not.

Physical pain lasted about a month, but the psychological pain has endured a lifetime, she said.

“It’s like something getting ripped from inside of me,” she said. “Something was forcefully taken from me.”