Lessons from ‘Pepeng’

MUD PATH Benguet residents carry packs of vegetables through a pathway carved out of mud and rocks that blocked a section of Halsema Highway days after Typhoon “Pepeng” hit northern Luzon in 2009. Heavy rain dumped by Pepeng triggered landslides in the Cordillera. —EV ESPIRITU

ROSALES, Pangasinan, Philippines — Intense rain pounded this town and the rest of Pangasinan province for days but Leny Flores, 67, and her family paid little attention to the torrential downpour that morning of Oct. 8, 2009.

She said her four grandchildren even went out to watch a movie at a mall a few kilometers from their home near the Agno River, Pangasinan’s longest waterway.

But anticipating that the rain would intensify and stay around for more days, Leny and her husband Andres, 69, had stored food supplies.

At 5 p.m. that day, their grandchildren were back in their two-story concrete home and the Floreses thought they would spend a normal evening.

Moments later, they heard cries and screams outside their home, prompting Leny to check the streets.

Article continues after this advertisementWhat she saw next was pandemonium.

Article continues after this advertisement“I was shocked to see floodwater rapidly rising. The neighborhood was in panic. Mothers and their children in tow were all crying and scampering for safety,” she recalled

That night, the Floreses accommodated at least 40 families, some with five or six children, in their house. “Parang sardinas (It’s like a can of sardines),” she said, describing their 150-square-meter, four-bedroom second floor.

The heavy rains spawned by Typhoon “Pepeng” (international name: Parma) triggered raging floodwater that rendered them sleepless that night.

Dike breached

The surge of water along the Agno River quickly topped three portions of the earth dike by a meter, Leny recounted. Nineteen more sections of the dike on both sides of the river in 11 other towns would breach that night.

The river traverses 16 towns and two cities in Pangasinan before draining into the Lingayen Gulf.

“I still shudder every time the memory of the flood returns but I have learned that it pays to be prepared,” she said.

Residents here have not experienced flood of that magnitude since then, Rosales Mayor Susan Casareno said. But she said the images of the tragedy had not been erased from her memory even after 10 years.

Most of the families living on top of the dikes have been resettled in housing projects in Barangay San Pedro West, Balincanaway and Palakipak.

But some villagers refused to be relocated, saying they wanted to stay near their source of livelihood.

Apart from Pangasinan, most parts of northern Luzon were hit by massive flooding as Pepeng lingered for almost two weeks.

The flood that occurred on Oct. 8, 2009, was a “one-in-80-years event,” said Tom Valdez, vice president for corporate affairs of San Roque Power Corp. (SRPC).

SRPC and the National Power Corp. (Napocor) were blamed for the massive flooding that inundated a large part of Pangasinan after the dam’s gates were hastily opened.

Valdez claimed that opening all the gates at 3 a.m. was a painful decision, “although the SRPC was only taking orders from Napocor that owns the San Roque Dam.”

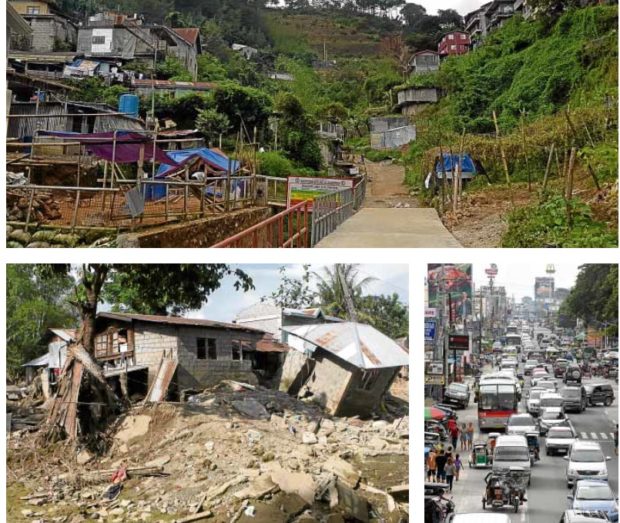

DEVASTATION AND RECONSTRUCTION A decade after Typhoon “Pepeng” hit, many residents of landslide-hit Little Kibungan in La Trinidad, Benguet, (top photo) have rebuilt their houses while others have sold their properties. In Pangasinan, the town of Rosales, which was submerged by floods in 2009 (bottom left photo), shows no trace of the devastation and has risen to become a major commercial center in the province (bottom right photo). —PHOTOS BY VALERIE DAMIAN AND WILLIE LOMIBAO

An investigating committee formed by the Department of Energy said the dam operators should have immediately made preemptive spillway releases.

Alexander Palada, Napocor division chief, said they released an enormous amount of water from the dam to prevent damage to the facility, and to stall water cresting over the dam that could lead to dam break.

The nonstop downpour caused by Pepeng submerged 973 of 1,356 villages in 36 towns and three cities of the province. Sixty-three people died and Pangasinan alone lost about P7.4 billion worth of infrastructure, crops, fish and livestock.

Records from the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council showed that Pepeng left 465 fatalities due to landslides and floods in northern Luzon.

Lessons learned

But SRPC and local officials have learned their lessons. SRPC regularly and promptly engages in information dissemination about the dam’s operations.

During typhoon months, the company gives updates on the dam’s water elevation, the inflow of water from upstream into the dam and the amount of water being released.

“There was lack of information and education campaign before Pepeng. SRPC has realized the importance of open communication with concerned agencies,” Valdez said.

The monitoring system of the Agno River has also been enhanced, for better information dissemination about its water level, Valdez said.

Former Rosales Mayor Ricardo Revita said casualties could be prevented if villagers would heed authorities’ calls for an evacuation.

He said preemptive measures should also include investment in rescue facilities and getting familiar with the town’s terrain or the existing operational conditions.

To avoid a repeat of the tragedy, officials of the Provincial Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (PDRRMC) of Pangasinan said they were engaging in information dissemination to prepare villagers for hazards present in their communities.

In the Cordillera, more than 200 people died, mostly due to massive landslides at the height of Pepeng.

Little Kibungan slides

In Benguet province, heavy rains caused by Pepeng triggered a mammoth mudslide that killed 77 people at Little Kibungan in Barangay Puguis, La Trinidad town, on Oct. 9, 2009.

The incessant downpour loosened the soil that cascaded from mountain slopes, burying the houses of the victims in the dead of the night.

But concrete and steel structures in the province have sprouted a decade after the deadly landslides.

Residents seemed unmindful of the warnings from the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) that their communities are identified as “high risk for deep-seated landslides.”

The Phivolcs even installed a landslide sensor technology and an early warning system to provide accurate and timely landslide warning and information to the communities.

Some of the original settlers in Little Kibungan sold their property. Others rebuilt their homes after the promised relocation site failed.

In 2010, then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo issued a proclamation allocating portions of the Benguet State University reservation at Barangay Tawang in La Trinidad as the relocation site for landslide survivors.

The settlers even started building the access road to the site but development stopped after several claimants in the area surfaced.

The provincial government spent some P23 million in rehabilitating the area, which included reinforcing the eroded slope that triggered the mudslide above the community with coir nets, and building a concrete canal that drains floodwater to the Balili River.

In July this year, the local government initiated regular drills for residents on evacuation protocols and procedures after several strong typhoons forced evacuations. —WITH A REPORT FROM KARLSTON LAPNITEN