Breaking South Koreans’ silence on campus bullying

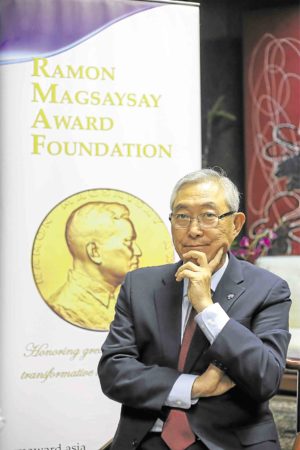

SON’S SUICIDE SENT HIM ON A MISSION Kim Jong-ki, one of the five recipients this year of the Ramon Magsaysay Award.

Behind South Korea’s technological feats and pop culture glitz is a hypercompetitive society where education is highly prized as a key to affluence and social mobility.

It exerts such tremendous pressure on the country’s youth, whose schools are not impervious to the dynamics that lead to campus bullying.

Twenty-four years ago, Kim Jong-ki’s only son Dae-hyun, then aged 16, was driven to suicide after being harassed and assaulted by a group of older students. The teen’s ordeal was witnessed by his classmates, who would later detail to Kim what his son went through.

The tragedy has since turned Kim, now 72, into an advocate whose passion and resolve are being recognized on Monday in the Ramon Magsaysay Awards. He is one of the five recipients this year of the Asian equivalent of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Adding to their anguish over the loss of Dae-hyun, Kim and his wife felt increasingly isolated by a society that they say refused to acknowledge school violence as an institutional problem.

Article continues after this advertisement“In Korea, (we) believe that the school is always very elegant,” Kim told the Inquirer in an interview. “It is a symbol of dignity… if I say something about school violence, the authorities think I hurt the good image of the school.”

Article continues after this advertisementBy the time of Dae-hyun’s death in 1995, many other youth suicide cases in South Korea had been linked to school bullying. Yet school violence remained a taboo subject as parents, teachers and government officials largely saw bullying as something children would eventually outgrow.

Hoping to change such a mindset, Kim tried to set up and register a civic organization for that purpose. The government officials in charge of approving it, however, were not too comfortable with the name he chose: Foundation for Preventing School Violence.

“They didn’t agree. They rejected it. I had to change the name to get approval from the government. So that’s why I changed it to Foundation for Preventing Youth Violence (FPYV),” he said with a chuckle. “But it’s a very sorrowful story, the name.”

Despite the initial pushback, FPYV has since helped bring national attention to a long-neglected issue. The organization has since been given credit for the steady decline in incidents of campus violence in South Korea.

The Ramon Magsaysay Foundation is honoring Kim for “his quiet courage in transforming private grief into a mission to protect Korea’s youth from the scourge of bullying and violence.”

Afraid of scandal

He is also being recognized for “his unstinting dedication” and “for effectively mobilizing all sectors of the country in a nationwide drive that has transformed both policy and behaviors toward building a gentler, nonviolent society.”

Kim recalled how he hit rock bottom when his son took his own life. He was then a businessman in his late 40s.

“At the time, I visited several NGOs (to seek advice) on this kind of despair. I was asking, How can I comfort myself? But nobody can give the right answer. Of course they don’t know about the school violence at the time.

“So, finally, I decided myself, to (personally) solve these matters,” Kim said.

It wasn’t easy to start a foundation anchored on an issue practically forbidden from discussion, Kim recalled. To talk about youth violence at the time was to open a Pandora’s box of sensitive topics: overzealous parenting and lax institutional systems, among others.

Victims of bullying and their parents were often too afraid to speak up, while school authorities and education officials would rather sweep the problem under the rug to avoid public scandal.

“Whenever I go to the office to discuss something, they would turn their backs immediately. They say ‘I don’t want to talk to you,’ ‘I have nothing to say to you,’” Kim said. “It was difficult.”

But Kim and his lean team of FPYV volunteers that he managed to assemble worked hard to develop a holistic, comprehensive program addressing school violence.

Crucial to this, he said, were the counseling sessions they held not just for the bullying victims but also for the perpetrators.

The foundation’s initiatives also included a mechanism for dispute mediation and a reconciliation program for the families involved. FPYV also launched a digital campaign against cyberbullying, an online certificate training program for youth advocates, and an incident detection and reporting system that involves teachers, counselors and the local police.

FPYV’s programs have evolved over the years to keep pace with the ever-changing face of bullying.

“The type of violence is changing. (Back then) physical attacks were very severe.” Nowadays, he said, it’s more of verbal and online harassment, sexual assaults, and racist attacks.

As further proof of FPYV’s success, its programs are now backed by legislation—the Special Act on Prevention and Handling of School Violence—that was passed in 2004 thanks to the foundation’s efforts. The law, considered the first of its kind in South Korea, requires government and school authorities to introduce deterrents to campus bullying.

Parenting

FPYV is now the largest nongovernmental organization addressing the problem of school violence in South Korea, with 13 regional branches and 100 partner schools across the country. Its projects have directly benefited about 50,000 students.

Recognizing that school violence transcends borders, FPYV has also found partners in Canada, Japan and Germany, forming a network for sharing best practices.

Kim knows much remains to be done. To this day, he said, suicide remains the No. 1 cause of death among South Korean youths, who are often under peer pressure and anxious about their academic performance and physical appearance.

Still, the best place to nip campus violence in the bud is the home, he said. “Parenting is important. (Parents) have to teach children to respect others.”

If you or someone you know is in need of assistance, please reach out to the National Center for Mental Health (NCMH). Their crisis hotlines are available at 1553 (Luzon-wide landline toll-free), 0917-899-USAP (8727), 0966-351-4518, and 0908-639-2672. For more information, visit their website: (https://doh.gov.ph/NCMH-Crisis-Hotline)

Alternatively, you can contact Hopeline PH at the following numbers: 0917-5584673, 0918-8734673, 88044673. Additional resources are available at ngf-mindstrong.org, or connect with them on Facebook at Hopeline PH.