‘El Dorado’ no more, but Itogon miners digging in

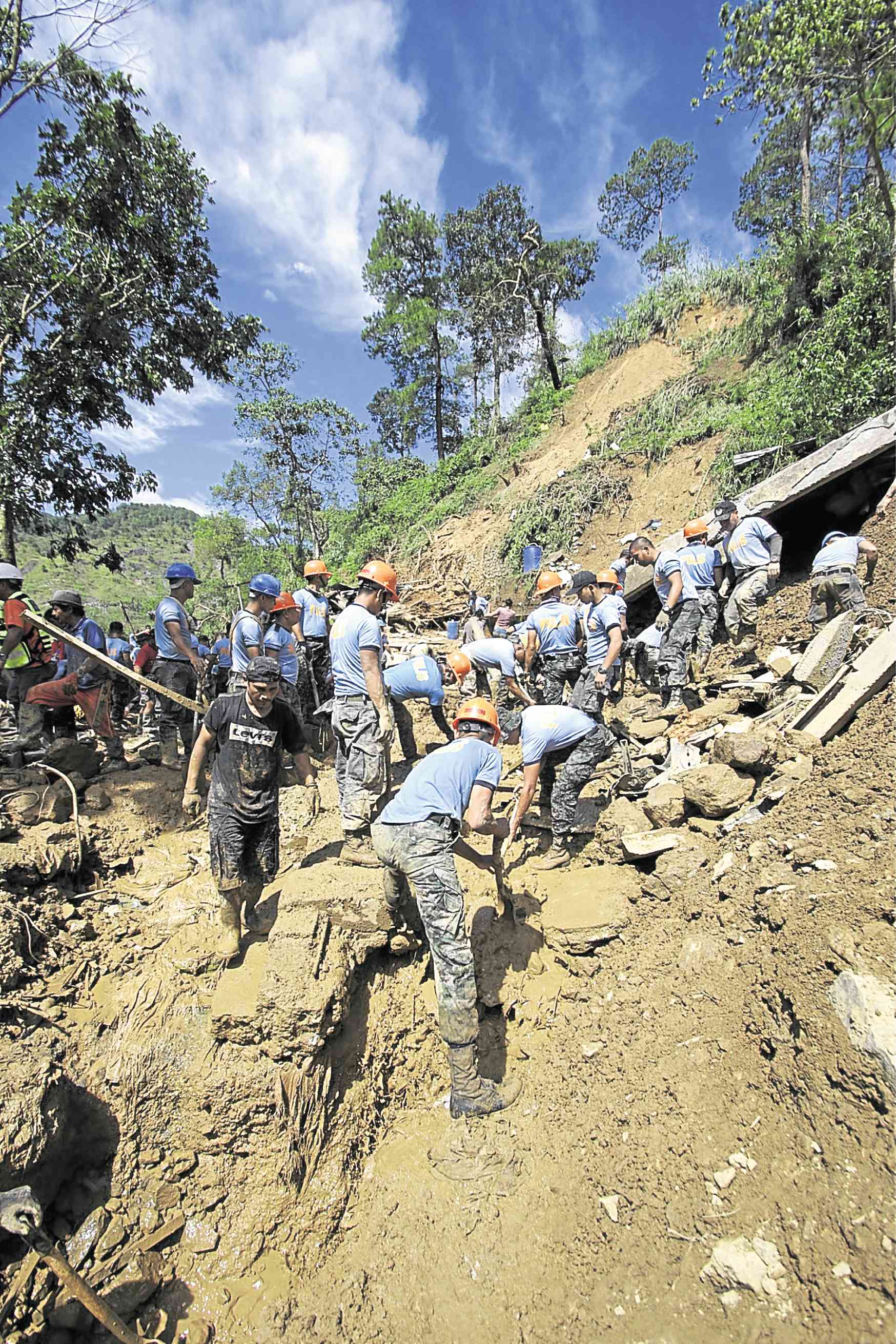

Smal lminers lost not only their homes, but also their dreams of living in “El Dorado,” the lost city of gold, which has been the town’s monicker since gold was first mined here centuries ago. —PHOTOS BY RICHARD BALONGLONG

ITOGON, Benguet — This mining town may need to undergo the most drastic change in its decadeslong history, and give up its reputation as “El Dorado,” the lost city of gold, according to European myth.

Dubbed as the “Land of Golden Opportunities,” Itogon is one of three Benguet towns with vast gold deposits, which have been mined by both corporate and small-scale miners for more than a century.

Gold is such a prized commodity here that a resolution passed in 2008 by local officials declared the mineral the town’s “One Town, One Product.” It has also been promoted as Itogon’s “pride of place.”

But officials may need to change this soon following a massive landslide that buried nearly 100 people at Barangay Ucab on Saturday.

When Typhoon “Ompong” (international name: Mangkhut) barreled through Benguet on Sept. 15, pocket miners took shelter in several shanties and a bunkhouse at the side of a mountain. Strong rains dragged down tons of earth from a mountainside, which buried these houses and killed 59 people as of Sept. 21.

Article continues after this advertisementThe national government’s immediate reaction was to close down all small-scale mining operations in the Cordillera, shocking Itogon residents who not only lost their loved ones but also their livelihood.

Article continues after this advertisementViolent resistance

Spanning 44,800 hectares, Itogon is Benguet’s largest town and is a first class municipality like Tuba and Mankayan, the other towns hosting corporate mines.

Historical accounts describe Ibaloi as miners before the Spanish colonization. Aware of the gold, Capt. Garcia Aldana y Cabrera tried to collect royal rights in 1620 from what is now Sitio Bua at Barangay Tuding.

In 1623, Sgt. Maj. Antonio Carreño de Valdes tried to make the same claims in what is now the Antamok mining area at Barangay Loacan.

Both Spanish soldiers met violent resistance and returned empty-handed.

Today, Itogon is host to two of the country’s oldest gold mining companies—Benguet Corp. (founded in 1903) and Philex Mining Corp. (founded in 1955).

While Benguet Corp. officially stopped operations in 1997, it still maintained ownership over its vast claims. Philex, meanwhile, has mining claims over portions of Barangay Ampucao.

DREAMS DASHED Miners and police personnel dig frantically to retrieve bodies buried by a massive landslide in Ucab, Itogon, Benguet, after Typhoon “Ompong” dumped monsoon rains in the area on Sept. 15.

Gold fever

All of Itogon’s nine villages have small-scale mining operations, but most of the 12,000 pocket miners are concentrated at Barangay Ampucao, Ucab, Virac, Tuding, Loacan and Gumatdang, according to Lomino Kaniteng, president of Benguet Federation of Small-Scale Miners.

A huge portion of the 50 kilograms of gold sold to both licensed and black-market dealers in Baguio City each week comes from Itogon tunnels.

Gold traders buy a gram of high quality gold for P1,500, while low purity gold can be sold for P900. Annually, these transactions could sum up to at least P2 billion.

The Itogon “gold fever” has lured people from neighboring towns and provinces. Some work seasonally while others have made Itogon their new home.

Almost all the fatalities in the Ucab landslide were from Ifugao province.

“We came here to make our lives better, but here comes fate,” said Daniel Bolhayon, a native of Hingyon town in Ifugao, who had settled in Ucab.

The fatalities were members of the mining association that operated the Lower Gomok Multipurpose Cooperative being managed by Bolhayon.

Some of the migrant miners occupied buildings formerly owned by mining companies while others put up houses on lands they had bought, among them the family of Wilbert Nagangi whose house sits at Sitio Firstgate atop the eroded mountainside in Ucab.

Nagangi, who used to work in the mines, now buys raw mine tailings, which are reprocessed to extract gold remnants. His wife, Lilia, their four children and his mother-in-law survived the landslide.

On Sept. 17, they were told they could no longer mine in the area. Two days later, Nagangi was informed that their home was no longer safe.

‘Balik-probinsya’ program

During a forum on Thursday, geologists from the Mines and Geosciences Bureau said the mountain—where Sitio Firstgate, 070 and Luneta are located—was prone to movement.

They said these areas were soaked by the weekslong monsoon rains in August and finally gave way when Ompong dumped more rains last weekend.

Of the 400 families who were forced to evacuate, 21 said they would avail themselves of the government’s “balik-probinsiya” program.

But Nagangi said returning to Ifugao was not an option. He has no property there and the livelihood opportunities are too few, he said. “We married and raised our children here. This is our home,” his wife, Lilia, said.

Most migrant miners from Ifugao used to plant “tinawon,” a premium rice variety grown once a year, said Ifugao Gov. Pedro Mayam-o, who traveled here to join Ifugao residents waiting for word on their missing relatives.

Because income from tinawon was not enough, Ifugaos sought alternative jobs like mining, Mayam-o said.

But they now have the same questions confounding Nagangi: “Where will we live? Will the government give us money to buy food and send our children to school?”

Despite the risks, Nagangi has been visiting his home to feed their pigs.

On Friday, Itogon Mayor Victorio Palangdan told the displaced families that livelihood projects, jobs and a relocation site were being worked out.

But until the promises are realized, Palangdan said the evacuees would have to rely on relief goods from the Department of Social Welfare and Development and private donors.

“They can stay in boarding houses or live with relatives for the meantime. We beg them not to go back until government geologists say it is safe,” he said.