Boracay shutdown spooks businesses

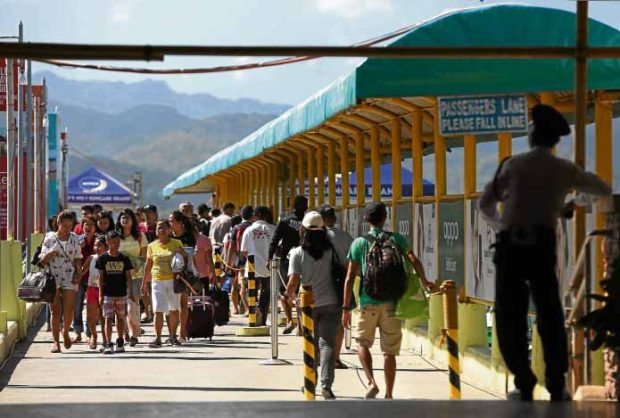

TERMINAL AND ENVIRONMENT FEES Tourists pay P100 exit fee at the Cagban port in Boracay. They earlier paid a P100 terminal fee at the Caticlan port and a P75 environment fee.

—PHOTO BY LYN RILLON

(Last of three parts)

BORACAY ISLAND, Aklan — Chiquita Magbanua sits on the white sand under the shade of coconut trees near Boat Station 3 at the southern end of this island, waiting for customers. It’s her favorite spot when selling bracelets, necklaces, anklets and other accessories made of shells.

When tourists come in droves during the peak months— from January to May — Magbanua sells her wares, earning P500 to P1,000 daily. During the rainy season and bad weather, she is penniless.

“If I do not sell anything for two days straight, I would need to borrow money from relatives or friends,” she told the Inquirer.

Magbanua, 56, a native of Manoc-Manoc village, said her earnings were barely enough to help meet her family’s needs. Her four grandchildren live with her.

Article continues after this advertisementReports that the national government will shut down the 1,032-hectare island scare Magbanua and other residents who depend on the island’s booming tourism industry.

Article continues after this advertisement“Closure … means hunger,” she said. “We are not sure of what will happen to us.”

After calling Boracay a “cesspool” and “full of shit,” President Rodrigo Duterte in February imposed a six-month deadline for government agencies and the local government to solve the resort island’s environmental problems.

Last month, the President said he was supporting the recommendation of an interagency task force for a shutdown of up to one year to facilitate the removal of illegal structures and to put up infrastructure to sustain Boracay’s tourism industry, which generated P56 billion in revenue last year.

The move, however, could adversely affect resorts and other businesses, and displace thousands of workers and others whose livelihoods depend on tourism.

Island workforce

Alma Belejerdo, Malay municipal planning and development officer, said registered local and foreign workers numbered 17,328 as of Dec. 31, 2017.

They included employees of hotels, resorts, restaurants and other commercial establishments, drivers of passenger vehicles, crew of passenger boats and those of other service sectors.

Unregistered workers were estimated at 9,365, according to the municipal government. Many employers did not declare the exact number of their staff to evade payment of the P200 occupancy permit per employee.

The workers come from Aklan and other provinces.

Shutting down Boracay could also cripple the economy of Malay town, which has jurisdiction over the island and derives most of its revenue from it.

A shutdown could also significantly affect the economy of Aklan province.

Annual revenue

In 2017, Malay’s revenue hit P508.470 million, of which P110.435 million (21.72 percent) was from its Internal Revenue Allotment.

Revenue from local sources reached P396.734 million (78.03 percent), according to the municipal government.

Rowen Aguirre, former municipal councilor and now special executive assistant for Boracay affairs, said 90 percent of the local revenue (P357 million) came from Boracay, such as fees from business and building permits, and environmental and terminal fees.

Terminal fee of P200

Each tourist going to the island pays P200 in terminal fees—P100 at the Caticlan port (the jump-off point from the mainland) and P100 when leaving the island at the Cagban port—and P75 in environmental fee, of which the province gets 15 percent.

The terminal fees are collected by the provincial government, which gets 80 percent. The municipal government gets 10 percent and Barangays Caticlan and Manoc-Manoc, 5 percent each.

The environment fee is intended “exclusively for environmental and tourism programs and projects in the municipality.”

Exempted from paying the fees are residents of Aklan, those holding a terminal pass, children age 5 years and below, and workers with valid company identification cards.

Assuming that at least half of the 2 million tourists who went to Boracay in 2017 paid the terminal fees, the provincial government would have collected at least P200 million.

Data obtained by the Inquirer from the municipal treasurer’s office showed that total collection for environmental fees hit P116 million last year — P99 million (85 percent) going to the municipal government and P17 million (15 percent) remitted to the provincial government.

According to the municipal government, the bulk of its share of the terminal fees goes to the collection of garbage in Boracay, which is transported in barges to the mainland.

Aklan’s cash cow

In his State of the Province Address in 2017, Aklan Gov. Florencio Miraflores called the Caticlan and Cagban ports and terminal a “cash cow” of the province.

Port operations raised P329 million in 2015 and P382 million in 2016.

From 2014 to 2016, gross revenue from toll and terminal fees, cargo fees and other port charges reached P861 million, while operation costs were P171 million for a net revenue of P690 million, according to Miraflores.

The Caticlan port also caters to passenger and cargo ships not coming from or bound for Boracay.

Hospitals, airport

Miraflores said the bulk of the net revenue (P486 million) from the two ports went to the three hospitals run by the provincial government — Dr. Rafael S. Tumbokon Memorial Hospital, Ibajay District Hospital and Altavas District Hospital.

Shutting down Boracay will hit the province hard, including the capital town of Kalibo, whose airport is the main gateway for tourists, according to the governor.

Last year, Kalibo International Airport had 75 to 80 international flights and 155 to 160 domestic flights weekly.

Hotels and restaurants in Kalibo also benefit from Boracay’s tourism industry.

Transportation services, including tourist buses and coasters and taxis, are booming as tourists shuttle from the airport to the Caticlan port, 68 kilometers away.

Seafood products

Aside from providing jobs, Boracay is also a growing market for seafood and agricultural products, especially from the northern areas of Panay Island.

An interagency task force composed of the departments of environment and natural resources, tourism, and interior and local government has formally recommended to President Duterte the suspension of all tourism-related activities in Boracay for six months starting April 26.

“The closure is necessary “to ensure undisrupted and unimpeded implementation” of measures aimed at correcting environmental and other violations on the island, according to the task force.

Highest monthly arrivals

Tourism Secretary Wanda Tulfo-Teo earlier said the closure of the island to tourists could include the months of June and July when tourist traffic is slow.

While the number of tourists is lower during the rainy season, there is no more “low season” on the island compared to 20 years ago.

The Department of Tourism reported that 159,708 tourists arrived in June and 153,791 in July last year, fewer than the 233,233 in April, which registered the highest monthly arrivals.

Henry Chusuey, chair of Henann Group of Resorts that operates five hotels on the island, said only those not complying with the law should be dealt with by the government.

If the shutdown pushes through, Chusuey said, “Who will feed our employees?” The group employs nearly 2,000 workers.

While most residents and property owners agree that the island’s resources need to recover from decades of overdevelopment, many doubt that the problems can be solved through a shutdown or even within the six-month deadline imposed by the President.

“What can the (Department of Environment and Natural Resources) and local government unit do in two months against what they have failed to do in four decades?” said former Western Visayas tourism officer Edwin Trompeta.

“To close the island is extremely ill-advised in the context of the economic activities in Boracay and its contribution to the economy,” Trompeta added.

Tricycle driver Wilson Talurong, who earns from P700 to P800 daily, fears the loss of his only source of livelihood.

“Why punish all of us? Just sanction the violators,” he said.

Balance

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)-Philippines said sustainable tourism could be achieved if there was balance among environmental protection, community benefits and visitor satisfaction.

“In the case of Boracay, the issue of environmental protection has been compromised,” WWF-Philippines said in a statement.

It added that the closure should deal with “the issue of restoring the natural systems and mitigating tourism and/or domestic activities that cause damage to the environment.”

The loss of income can be recovered, said Jojo Rodriguez, vice chair of Sangkalikasan Producer Cooperative, which has conducted an artificial reef project aimed at rehabilitating Boracay’s almost severely damaged coral reef system.

“If we lose the island through negligence and greed, that will be forever,” Rodriguez said.