An ancient holy book symbolises the fate of Sarajevo’s Jews

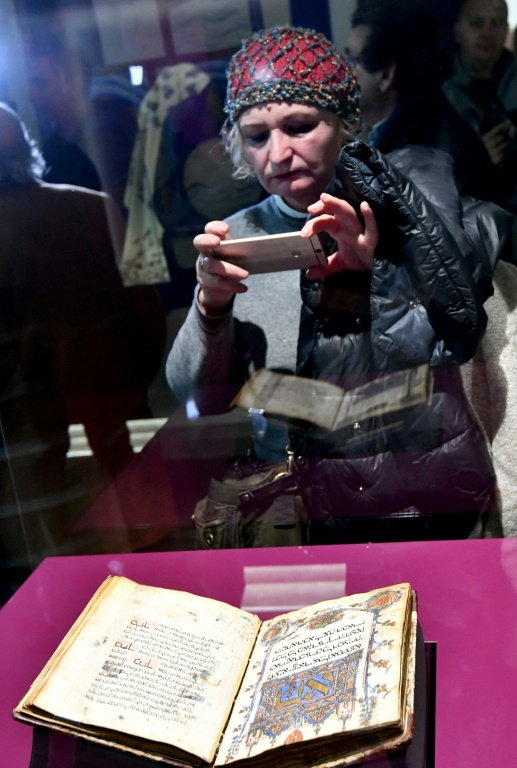

The 14th century illuminated ‘Hagaddah’ holy book which was hidden from the Nazis and is now on permanent display at Bosnia’s National Museum. Image: Elvis Barukcic / AFP

Eli Tauber, a pillar of Sarajevo’s Jewish community, waited anxiously for worshipers to arrive at the synagogue as there must be at least 10 men present before starting the Sabbath prayers.

To the historian’s great relief 11 men and a woman, most of them elderly, turned up for the service led by a local man who represents the Jews on Bosnia’s ecumenical council.

The rabbi lives in Israel and only comes to Sarajevo for the Jewish Passover and New Year holidays.

No more than 800 Jews still live in the Bosnian capital, according to their community’s 74-year-old leader, Jakob Finci.

Before World War II they numbered around 12,500, accounting for 15 to 20 percent of the city’s population, but many were killed during the Holocaust.

Still Jews remain part of the multi-cultural and religious identity of Sarajevo alongside Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Croats and Bosnian Muslims.

The symbol of the story of Bosnia’s Jews is a 14th-century treasure — the famous Sarajevo Haggadah holy book, containing the biblical text of Exodus read by Jews at Passover.

The ancient manuscript on bleached calfskin, illuminated in copper and gold, has been on permanent display at Bosnia’s National Museum since last month.

Flames of the Inquisition

The ancestors of Sarajevo Jews first found refuge in Bosnia, then part of the Ottoman Empire, after being expelled from Spain by the Roman Catholic royals in 1492.

The Haggadah came with the Sephardic Jews fleeing Spain, originating most likely from the region near Barcelona. According to Tauber, it was brought to Sarajevo in the 17th century, escaping the flames of the Inquisition.

Then in the late 19th century a Jewish family in financial difficulty sold the holy book to the national museum.

During World War II, Sarajevo was terrorized by the Ustasha, Croat allies of the German Nazis who controlled Bosnia.

When a German officer came to the museum to seek the Haggadah, “its director Jozo Petrovic, a clever man, replied that another officer took it away the day before,” historian Enver Imamovic, 77, told AFP.

The Haggadah had been hidden from the Nazis under the threshold of a mountain hut near Sarajevo.

The city’s Jews however were rounded up and grouped in the synagogues “before being transported to the concentration camps,” said Zanka Dodig, curator at the Jewish Museum housed in Sarajevo’s oldest synagogue.

The names of some 12,000 Jews who never returned are listed in a large book hanging on a rope from the ceiling of the Great Temple, the synagogue constructed in 1581 next to the city’s famous Bey’s Mosque.

After surviving centuries of turmoil, the Haggadah was stolen by an indebted national museum employee in 1954, but the medieval treasure was recovered “on the border with Italy,” Imamovic said.

In June 1992 during the Bosnian war following the break-up of Yugoslavia, when Serbs began shelling Sarajevo in a three-and-half-year-long siege, Imamovic took the Haggadah and put it in a safe at the national bank.

When the conflict ended in 1995, the Haggadah was put on display only on special occasions.

But now, a secured and air-conditioned showcase financed by the French government has put the holy book on permanent display.

‘A good sign’

Yugoslav Nobel literature laureate Ivo Andric famously wrote that Bosnia, “where four different religions live close to each other, would need four times more love, mutual understanding and tolerance than other countries.”

That dream has rarely been the reality, but Sarajevo Jews still express optimism.

“I really consider Sarajevo a Jewish city since the Jews found some peace here,” Tauber said.

The doors of the four-tower Ashkenazi Synagogue, built in 1902 on the banks of the Miljacka river are “always open… No one asks for an identity card, unlike (synagogues) in Zagreb or Belgrade,” he said.

Although few worshippers can be found at services, community leader Finci wants to believe that the history of Sarajevo Jews will go on.

Admittedly, he said, “for the first time in more than 450 years, there are fewer than 1,000 Jews in Sarajevo.”

During Bosnia’s inter-ethnic war, in the 1990s, two-thirds of the estimated 1,500 Jews fled the country.

But 40 percent of those have since returned and there are no more departures, Finci noted.

“In 2016, there were 12 newborns, in 2017 a little less, but it’s a good sign.” AB

RELATED STORIES:

Kenyan doctor performs brain surgery on wrong patient

Japan car giants team up to build hydrogen stations