A driver’s special trip from a scare to a smile

Book an Uber and there’s a chance you’ll have Marlon Fuentes as your friendly driver.

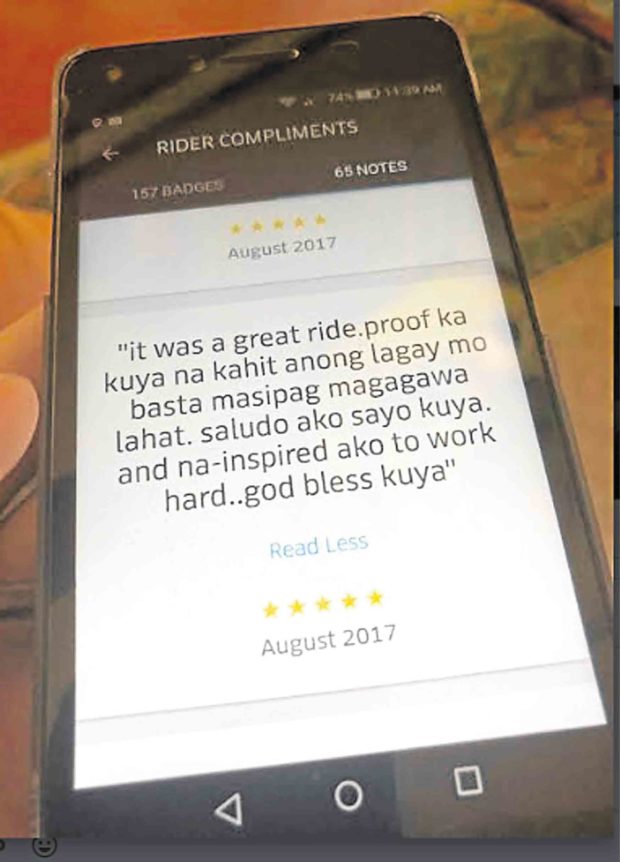

On your phone’s screen will be his profile and first-rate stats — over 1,700 trips taken, 157 badges, including 93 for “Excellent Service,” and a 4.81 rating. But you’ll also find a plea for understanding.

“I have Tourette Syndrome,” he declares in the About Me section. Inside his silver Toyota Innova you’ll find a sign that adds: “Hope you understand my condition. Thank you!”

One passenger, Hazel Alvero, had Fuentes as her Uber pilot on Jan. 15, the same day he placed the sign at the back of his driver’s seat. Recounting her ride later on a Facebook post, she said: “Stepping in, I noticed the driver’s unusual movements. First thought was, ‘Can I still cancel?’”

Alvero was of course not the first to have that initial reaction upon encountering Fuentes, who carries on with a steady sense of purpose and positivity despite having a neurological disorder since childhood.

Article continues after this advertisementVaried symptoms

Tics associated with Tourette Syndrome (TS) include rapid eye blinking, facial twitches, repetitive jerks of the shoulder, involuntary hand-tapping, throat clearing, grunting, and mumbling. In more complex cases, the symptoms lead to self-harming movements or an outburst of slurs or obscenities.

The condition was named after the French neurologist, Georges Gilles de la Tourette, who in 1885 chronicled nine patients with childhood-onset tics and involuntary vocal noises that would later be understood as the distinctive features of the condition.

“Some people ask me, ‘Why don’t you just stop it?’” Fuentes said in an interview with the Inquirer. “I say, ‘Who would choose to be like this, to be laughed at by people?’ I want to stop it, but it’s not that simple.”

There is no “typical” TS patient, but those who have the condition share a common experience of being isolated or ridiculed.

“I would get scolded at home and laughed at in school, even embarrassed by teachers,” said Marlon Barnuevo, cofounder of Philippine Tourette Syndrome Association (PTSA), which has about a hundred members who include Fuentes.

Two of the rave reviews received by Fuentes from his safely conveyed—and emotionally touched—passengers.—PHOTOS BY MATTHEW REYSIO-CRUZ

Lifelong question

Now aged 38, Fuentes started showing TS symptoms at age 7 but only got diagnosed upon reaching adulthood, after watching a television feature on a PTSA member and recognizing that person’s tics as similar to his own.

“My lifelong question had been answered,” he said.

After getting in touch with Barnuevo through a number posted online, Fuentes was soon joining PTSA gatherings and got to know people like him for the first time.

“When we’re together, it’s like the world is ours. If you’re with us and don’t have a tic, it’s like you’re the one who isn’t normal,” he said.

According to Barnuevo, everyday activities like commuting can be a nightmare for those with TS, who have to endure long stares from a crowd of strangers, in chance encounters that can scar one’s self-esteem for life.

Jose Robles, a pediatric neurologist at Philippine Children’s Medical Center and St. Luke’s Medical Center, said the tics could interrupt speech, making it difficult for TS patients to explain things clearly.

Aggravated by stress

“When in a hurry or finishing deadlines, stress will further increase attacks … When eating, they can choke if the attacks are predominantly in the mouth and throat,” Robles said.

There is still no cure for TS, although there are treatments to help manage the tics. Fuentes once tried taking medication, but stopped after a month after it caused drowsiness and memory lapses as side effects.

“I tell (PTSA members) that probably one of the reasons we have TS is to inspire other people. If we can show them that we can do it, anyone can do it,” Barnuevo said.

And it was apparently the effect Fuentes had on Alvero, one of his satisfied passengers, who in her Facebook post commended the driver for the safe trip and his professional conduct behind the wheel.

“I wanted to share how it felt to judge and be proven wrong,” she told the Inquirer.

After Alvero’s viral post, which has been shared more than 31,000 times as of this writing, came to the attention of the Uber management, the company rewarded Fuentes with a “six-star” rating, making him only the second out of the thousands of Uber drivers in the country to receive that recognition, according to the Uber head of communications, Cat Avelino.

“He can serve as an inspiration for other people, (showing) that you should not let your physical limitations get in the way,” Avelino told the Inquirer.

Butt of jokes

Fuentes was 17 and fresh out of high school when he found his first job as a construction worker in Cavite province. It was his first taste of being a butt of work site jokes; he actually felt glad when the building project was finally finished.

But then the dreaded time came for him to find another job, one that would entail being interviewed during the application process. “I almost gave up. Whenever I applied, I was rejected. I looked at the other applicants and thought: ‘This company has so many choices; why would it choose me?’”

Fuentes once got hired in a tire factory in Laguna province, only to be fired on his first day on the job because “they couldn’t believe I was fit to work.” This was even after he passed the preemployment medical checkup.

An assortment of small-time jobs followed, mostly allowing Fuentes to work in relative isolation and away from public gaze. He made doormats and wash rags, bracelets and rosaries. There were also months spent working in a fiberglass factory and selling cooking oil in the streets of Pandi, Bulacan, his hometown.

Protective wife

Amid these struggles, Fuentes met Rio, a fellow factory worker who in 2003 would become his wife—and fiercest protector.

“She’s the one who confronts people when she sees that they’re staring or laughing at me,” he said. “She turns the tables on them by asking: ‘Do you have a problem with my husband?’”

The couple were soon raising two sons—and Fuentes had to find a more stable job. Thanks to a friend who owned a jeepney, he learned how to drive and earned a driver’s license in 2005.

A tricycle operator was the first to trust him on the road despite his condition. By 2016, he had “graduated” to driving trucks.

“In all the years I’ve been driving, I never got into an accident,” Fuentes said. “Some of my passengers say they prefer riding with me because I drive more safely than others. People like me, they say, are twice as careful.”

Last year, Fuentes’ brother-in-law returned after years of working in Saudi Arabia, bought a car, and asked him to be its Uber driver.

‘Don’t worry’

During his first few months on this job, Fuentes encountered passengers who would grow anxious during the ride upon noticing his tics. Some even asked to be dropped off while still kilometers away from their destinations.

“Once, there was this nanny and the child under her care. (I heard her) call her employer on the phone to ask that they be ‘monitored’ because there’s something strange happening during the ride,” he recalled.

“I turned to tell her that I’m sick but not a bad person. But she just looked at me; I don’t know if she understood.”

Fuentes found himself explaining his condition to riders in every trip. “I think they were thinking, ‘Is this guy on drugs? Is he drunk? Is he having a heart attack?’”

“So I thought of putting up the sign,” he said. “Now I often see my passengers smiling at me. It’s like they’re trying to tell me, ‘Don’t worry. We understand you.’”