Scientists find massive Mayan society under Guatemala jungle

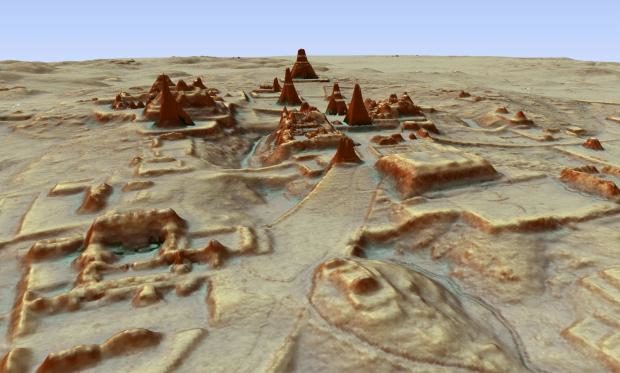

This digital 3D image provided by Guatemala’s Mayan Heritage and Nature Foundation, PACUNAM, shows a depiction of the Mayan archaeological site at Tikal in Guatemala created using LiDAR aerial mapping technology. Researchers announced Thursday, Feb. 1, 2018, that using a high-tech aerial mapping technique they have found tens of thousands of previously undetected Mayan houses, buildings, defense works and roads in the dense jungle of Guatemala’s Peten region, suggesting that millions more people lived there than previously thought. (Photo by CANUTO and AULD-THOMAS / PACUNAM via AP)

GUATEMALA CITY — Researchers using a high-tech aerial mapping technique have found tens of thousands of previously undetected Mayan houses, buildings, defense works and pyramids in the dense jungle of Guatemala’s Peten region, suggesting that millions more people lived there than previously thought.

The discoveries, which included industrial-sized agricultural fields and irrigation canals, were announced Thursday by an alliance of US, European and Guatemalan archaeologists working with Guatemala’s Mayan Heritage and Nature Foundation.

The study estimates that roughly 10 million people may have lived within the Maya Lowlands, meaning that kind of massive food production might have been needed.

“That is two to three times more (inhabitants) than people were saying there were,” said Marcello A. Canuto, a professor of Anthropology at Tulane University.

Researchers used a mapping technique called LiDAR, which stands for Light Detection And Ranging. It bounces pulsed laser light off the ground, revealing contours hidden by dense foliage.

The images revealed that the Mayans altered the landscape in a much broader way than previously thought; in some areas, 95 percent of available land was cultivated.

“Their agriculture is much more intensive and therefore sustainable than we thought, and they were cultivating every inch of the land,” said Francisco Estrada-Belli, a Research Assistant Professor at Tulane University, noting the ancient Mayas partly drained swampy areas that haven’t been considered worth farming since.

And the extensive defensive fences, ditch-and-rampart systems and irrigation canals suggest a highly organized workforce.

“There’s state involvement here, because we see large canals being dug that are re-directing natural water flows,” said Thomas Garrison, Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Ithaca College in New York.

The 810 square miles (2,100 square kilometers) of mapping done vastly expands the area that was intensively occupied by the Maya, whose culture flourished between roughly 1,000 BC and 900 AD. Their descendants still live in the region.

The mapping detected about 60,000 individual structures, including four major Mayan ceremonial centers with plazas and pyramids.

Garrison said that this year he went to the field with the LiDAR data to look for one of the roads revealed.

“I found it, but if I had not had the LiDAR and known that that’s what it was, I would have walked right over it, because of how dense the jungle is,” he said.

Garrison noted that unlike some other ancient cultures, whose fields, roads and outbuildings have been destroyed by subsequent generations of farming, the jungle grew over abandoned Maya fields and structures, both hiding and preserving them.

“In this the jungle, which has hindered us in our discovery efforts for so long, has actually worked as this great preservative tool of the impact the culture had across the landscape,” noted Garrison, who worked on the project and specializes in the city of El Zotz, near Tikal.

LiDAR revealed a previously undetected structure between the two sites that Garrison says “can’t be called anything other than a Maya fortress.”

“It’s this hill-top citadel that has these ditch and rampart systems… when I went there, one of these things in nine meters tall,” he noted.

In a way, the structures were hiding in plain sight.

“As soon as we saw this we all felt a little sheepish,” said Canuto said of the LiDAR images, “because these were things that we had been walking over all the time.”