Kin of drug war victims to PNP chief: What move on?

Emily Soriano, Angelito’s mother, bewails that her son now lays dead in Tala Cemetery while the suspected gunmen who killed him still roam free. “Be, masisisi mo ba si Mama na sinisisi ka niya kasi hindi ka nakinig sakin na ’wag ka na umalis noong gabing ’yon?” she wept.

Still in mourning a year after their loved ones were slain, families of victims of extrajudicial killings in Caloocan City condemned Philippine National Police chief Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa’s latest pronouncement urging them to “move on.”

Dela Rosa made the statement last Saturday during the Quezon City Police District’s giftgiving program attended by nearly 700 children, most of whom were orphaned by President Duterte’s war on drugs.

“Do you (Dela Rosa) really think it’s that easy for us to get over their deaths? You are not the one who lost someone,” said Emily Soriano, the mother of 15-year-old Angelito, who was among the seven people gunned down by masked men in Barangay 176, Bagong Silang on Dec. 28, 2016.

“It’s been a year since they died and that’s it? Maybe that’s why your nickname is Bato, because your heart is just as hard as stone,” Soriano added.

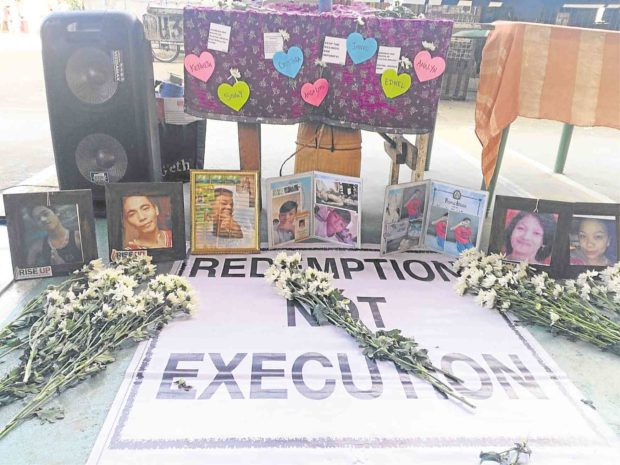

Led by ecumenical rights group Rise Up, Soriano and the kin of the other six held a vigil at the barangay’s covered court and on their graves in Tala Cemetery to commemorate their first death anniversary.

Article continues after this advertisementThe anniversary coincided with the Biblical celebration of the Day of the Innocents, which commemorated King Herod’s orders to execute male babies in Bethlehem in order to kill baby Jesus.

Article continues after this advertisementDuring the vigil, the group demanded an end to President Duterte’s war on drugs, which they likened to “Herod’s massacre.”

‘Palit-ulo’

“These seven are just some of the many killed (in Caloocan City under the war on drugs). Now we will no longer stand for another Herod to sow death among our nation,” said Norma Dollaga, Rise Up secretariat.

The seven were gunned down by at least three motorcycle-riding men believed to have been targeting a drug suspect.

Among those killed were Angelito, 15; Jonnel Segovia, 15; Sonny Espinosa, 16; Kenneth Lim, 20; Ednel and Cristina Santor; and a pregnant Analyn Diamla.

Their families maintained that the seven were not criminals nor involved in illegal drugs and were likely victims of “palit-ulo,” alleging that the gunmen’s target was Jay-R Santor, a drug suspect who earlier surrendered to authorities under the government’s “Oplan Tokhang.”

Santor owned the two adjacent shanties where the seven were gunned down. The teenagers had gone to attend a birthday party for one of Santor’s sons.

A year later, their families said they found it difficult to move on from their untimely deaths, lamenting how the gunmen snuffed out their futures.

Jimmy Segovia, Jonnel’s father, said that sometimes, he would imagine that his son was still out there peddling buko juice, just like when the boy was still alive.

Emily Soriano, Angelito’s mother, bewails that her son now lays dead in Tala Cemetery while the suspected gunmen who killed him still roam free. “Be, masisisi mo ba si Mama na sinisisi ka niya kasi hindi ka nakinig sakin na ’wag ka na umalis noong gabing ’yon?” she wept.

Processing grief

“It’s so hard to process. I still can’t accept that he’s gone. I already told him that night not to visit his friends because that place was dangerous and he still went,” he said.

At the time, he said, Jonnel was already home when their friend Edward Villanueva invited them to Santor’s house. Jonnel ended up getting shot 13 times during the attack while Villanueva survived.

“Imagine, 13 times. Like they were animals being slaughtered. My son did not deserve that,” Segovia said.

Miguelito, Angelito’s brother, echoed the sentiment. “I may not know anything about how my brother died but what I do know is that he was a student with dreams and a future ahead of him. And then getting told to move on? They know nothing of the pain we are dealing with.”

Soriano pledged on Angelito’s grave that she would continue seeking out justice for her son.

“To all of us who fell victim to this war on drugs, let us unite together and seek justice for the deaths of our sons. To others, please, don’t wait for this to happen to you as well,” she said.