US states consider using powerful fentanyl to execute inmates

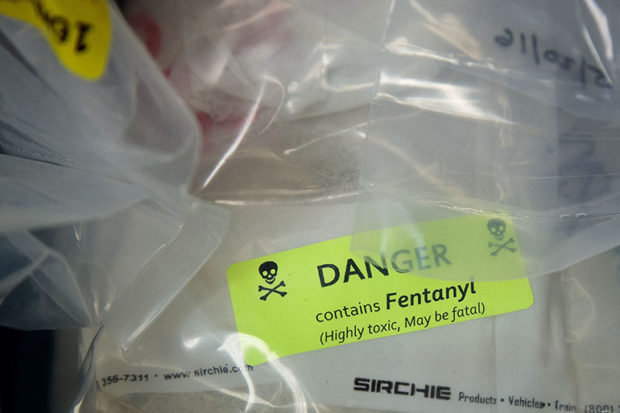

FILE PHOTO

Fentanyl, a potent drug playing a major role in the US opioid crisis described by Donald Trump as a “plague,” is now under consideration for use in lethal cocktails to execute inmates.

The states of Nevada and Nebraska are planning to supply prison executioners with the opioid painkiller — which killed more than 20,000 people in the United States in 2016 — drawing criticism from doctors and activists who call the move a dangerous human experiment.

They warn of serious risks posed to death row prisoners, who effectively become guinea pigs against their will.

Fentanyl, which also acts as an anesthetic, is 50 times more powerful than heroin and up to 100 times stronger than morphine.

The bid to use fentanyl as a capital punishment tool is due to a shortage of drugs normally used in lethal injections and is not grounded in scientific analysis, according to Deborah Denno, an expert on lethal injection at Fordham University.

“The use of fentanyl by states greatly heightens the risk of a botched — and therefore painful — execution in the ways that past execution drugs have demonstrated,” she told AFP.

“Each new drug introduces yet another reckless exercise by states in selecting protocols based solely on their accessibility.”

The acute shortage of deadly drugs has lasted several years, as several major laboratories refuse to stock US prisons to avoid the bad PR of being associated with the death penalty.

Lethal injections are generally carried out with three substances administered in succession: the first induces a coma, the second paralyzes, and the third stops the heart.

‘Chaotic’ executions

But in several recent executions the first drug failed to render prisoners fully unconscious, causing them intense suffering prior to death.

“Over the past forty years of their existence, lethal injection executions have never been more chaotic and irresponsible than they are now,” Denno said.

Last month the state of Ohio had to halt the execution of a critically ill convict, after prison officers failed to find a vein strong enough to receive the lethal dose.

The controversy over lethal substances is contributing to the slowed pace of executions in the United States, a trend confirmed by a report released Thursday by the independent Death Penalty Information Center.

“The long-term national decline of the death penalty continued in 2017, despite efforts by the few states that scheduled executions to carry them out at all costs,” the report said.

The US carried out 23 executions in 2017, its second lowest number since 1991 and a far cry from the 98 executions in 1999.

Just eight states performed the executions, while the death penalty is allowed in 31 states.

New execution methods The year should also close with the courts handing down 39 total death sentence verdicts — again the second lowest since the Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional in 1972, a decision overturned four years later.

Just 55 percent of Americans say they support the death penalty, according to a Gallup poll — the lowest share in 45 years.

The controversies over injections are pushing states to consider returning to the electric chair or exploring new methods of execution.

In a controversial move the state of Mississippi in the spring legalized using nitrogen gas chambers if lethal injections are not possible.

“There is no solid information on how such an execution would be conducted,” said Denno, emphasizing that it could also violate the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution prohibiting “cruel and unusual punishment.” / ae