Desaparecido: Remembering Ate Tish

TRIBUTE TO THE FALLEN Bantayog ng mga Bayani sculpture remembers the martyrs of martial law.

Forty-two years ago was the last time Ate Tish was seen in front of an ancient church in Paco, Manila. She was a student activist who had gone to live with impoverished farmers in Quezon province in the early years of martial law.

In November 1975, we lost her to the savage agents of martial law.

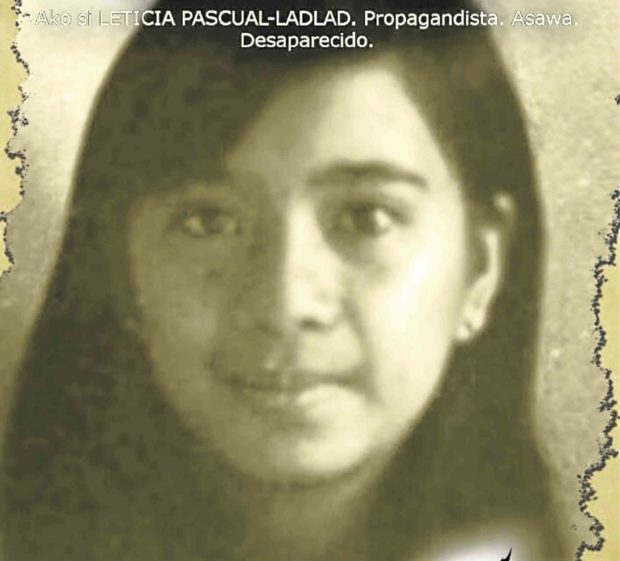

Ma. Leticia Quintina Jimenez Pascual-Ladlad: desaparecido, just one among thousands who vanished into the shadows, most probably tortured and killed, their remains never found.

But there’s no forgetting Ate Tish who would tag me along, a boy of about 7 or 8, to watch stage plays, musicals and movies. She cajoled me into reading books and would hand me poems to read out loud.

Even in my rough, brattish boyhood, she welcomed me to a whole new world. At 12, she enrolled me in a studio to learn classic guitar.

Article continues after this advertisement

LOST TO MARTIAL LAW Ma. Leticia Quintina Jimenez Pascual-Ladlad

Bookstore regular

Article continues after this advertisementAn older brother, Kuya Ray, in bursts of memory, would fondly recall how he’d sing a duet with Ate Tish: Peter, Paul and Mary’s “Stewball,” with her on the guitar. Ate Tish was a mean guitarist. And in the duet, she’d sing second voice.

It was from her that I first heard the song “Try to Remember,” from the Broadway classic “The Fantasticks.”

On the website of Bantayog ng mga Bayani, where Ate Tish’s name was engraved on the Bantayog Wall of Rememberance among other martial law heroes, she was described as “laman ng bookstore (a bookstore regular),” with philosophical works being part of her reading fare. Her intellectual interests were nurtured by her parents.

Her father, a pediatrician, was once director of the Philippine General Hospital (while) her mother was a professor in graduate school. (Also included in Bantayog’s wall is her cousin, the late Inquirer editor Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc).

WALL OF REMEMBRANCE Names of martial law heroes engraved on the wall include that of Inquirer editor Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc.

“Pascual excelled as a student at the University of the Philippines in Los Baños, where she was expected to graduate magna cum laude in agricultural chemistry. But her nose was not always buried in books.

Tish, as friends called her, joined Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan and cofounded the UP Cultural Society and the League of Editors for a Democratic Society. In her third year she became the first woman editor of the student paper Aggie Green and Gold.

Politically aware

“Although Pascual grew up in the city and had a relatively sheltered middle-class upbringing, she rapidly became aware of the social and political realities that the country’s poor had to live with. Her writings began to show this deepening understanding of her country’s politics, especially when she started making extended visits to Southern Luzon farming communities and learned about their problems.

“Her parents were worried for Tish (who was frail), but they realized that it was a decision they could understand and respect, and admired her for it. When (former President Ferdinand) Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus in 1971, she left her studies and continued to work among the peasant farmers in Laguna and Quezon provinces. In 1973, she married fellow activist Vicente Ladlad and gave birth to their daughter in 1975.

“In late November of 1975, she left home to meet with some comrades in the area of Paco Church in Manila; she was expected to return later that day. The group all disappeared without a trace. Parents and friends looked for her at the Defense and Constabulary headquarters but their efforts were fruitless.”

Ate Tish disappeared without a trace, and all I have now are fading photocopies of an article written by Mommy to honor her, and another by Kuya Ray.

There are also printouts of a few news releases where she was cited, tributes from UP and Bantayog, an Inquirer column by cousin Rina Jimenez-David, and oh yes, her last long letter to my parents dated Oct. 2, 1972, and written in a remote, impoverished farm somewhere in Quezon.

It was surreptitiously written in her small, neat handwriting with distinctive girlish strokes, 11 days after martial law was proclaimed.

My sister vanished at age 25. She would have been 67.