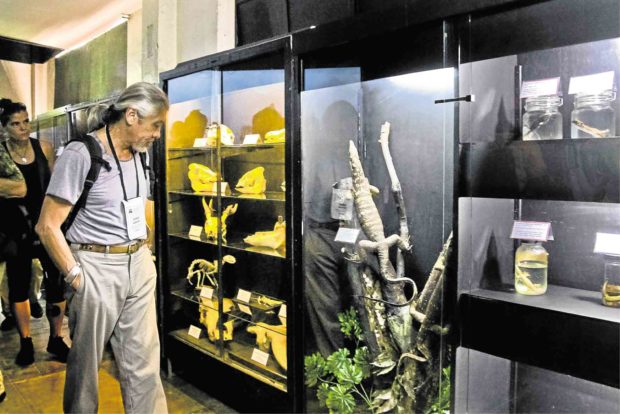

A visitor stops at a display of reptiles at the UPLB Museum of Natural History.—KIMMY BARAOIDAN

LOS BAÑOS, Laguna — Museums of natural history usually conjure up images of dried and pressed brown leaves that bear labels with tongue-twisting scientific names in Latin, dead insects spread out and pinned on boards behind glass panels, and preserved animal specimens in glass jars — all gathering dust in a musty room with a faint smell of formalin lingering in the air.

Though hundreds of people still visit these museums daily, the larger public is captivated by science museums with high-tech interactive exhibits and art museums with ‘Instagrammable’ displays.

“A public notion of museums is old, [dusty] collections,” said Dr. Juan Carlos Gonzalez, director of the Museum of Natural History (MNH) at the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB), during the First Philippine Natural History Museums and Collections Summit held in the Laguna campus recently.

According to Gonzalez, there is a need to revitalize exhibits and make them more interactive. People should be allowed to touch specimens, he said.

Visitors observe live ants in a glass case. —CHRIS QUINTANA

More engagement

“One of the major turning points of museum is transition from a totally no-touch to a totally touch museum. So this has revolutionized the museum experience,” said Dr. Lawrence Liao, a professor at Hiroshima University in Japan, one of the summit speakers.

Some local museums still prohibit visitors from touching the displays.

“In the new museology, you have an object for exhibit and another object for study wherein students and professors can touch and look at it. You call them study collections. These are not being promoted in the Philippines,” said Amado Alvarez, head of the National Committee on Museums, which is under the Subcommission on Cultural Heritage of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Science museums have more interactive exhibits, but these are more physics- and chemistry-oriented, said Alyssa Aranda, 18, a Grade 12 student. Biology, however, is more on observation to appreciate the plants and animals, she said.

The high-tech nature of science museum exhibits can sometimes veer away from actual learning.

Tamaraw skeleton —CHRIS QUINTANA

Abuse of technology

“The abuse of technology can be detrimental because it becomes all play. There is no effect,” Alvarez said. In one museum he visited once outside the Philippines, he said, the exhibits were all rendered in animation and virtual reality.

“Don’t show me a drawing of a leaf that is burning. I do not have engagement with that. That is not what I want. I want the real thing,” he added.

Aranda and two other Grade 12 students—Mary Joy Ancheta, 18, and Akemi Ray Goshi, 17,—also prefer the real thing—either actual preserved specimens or live plants and animals situated in their natural environment.

“The real thing sticks to your mind. What it looks like, what its real size is, the small details that only you can see like the hairs on a bat, you remember those,” Goshi said.

At the UPLB MNH, there are live animals on display, such as some species of local endemic frogs. Visitors can also touch some of the live specimens, such as the stick insect (Pharnacia magdiwang), which is endemic to Sibuyan Island in Romblon province.

Fungi exhibit —KIMMY BARAOIDAN

Story behind objects

Alvarez stressed the importance of the narrative attached to the objects.

Most natural history museums just show the object’s scientific name, its common name, and other related biological information. The role of the curator or guide is to impart to the visitors the stories behind the objects on display.

Ancheta said she would appreciate museum guides who share information about the origin of a specimen and its name, and the scientist who obtained it.

Natural history museums need not spend a fortune to make their exhibits more interactive and engaging, Alvarez said. “Why do you create art? It’s to irritate the status quo, meaning people to think otherwise. And I think museums can do that without expensive things.”

“Give them [museum visitors] problems to solve,” he said. “Problem-solving, that is the only way you can engage them.”

A father and his son learn from a display on insects. —CHRIS QUINTANA