Early tattoo designs

Tattooing was prevalent during the pre-Hispanic and early colonial period in the Philippines. The practice was common among the Bontok, Ifugao and Kalinga people, the major warrior groups in the Cordillera, in the 16th century.

“Batok” is the general term for tattoos. But tattooing is so widespread in the region that there are local equivalents in other Cordilleran languages: whatok (Butbut Kalinga), batók (Kalinga), fatek (Bontoc), bátok (Ifugao), bátek (Ilocano, Ibaloy, Lepanto and Sagada Igorots), and bátak (Kankanaey).

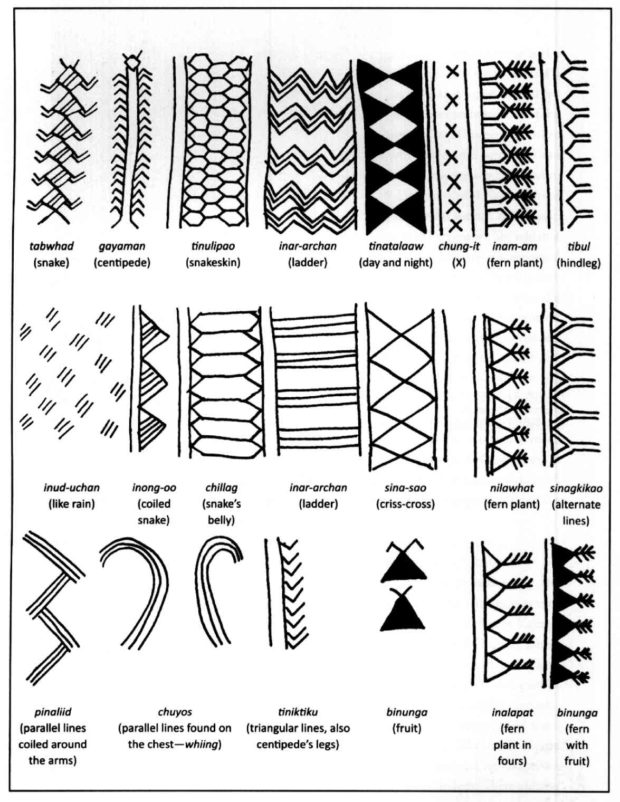

Most tattoos documented in the pre- and early contact periods were of abstract, geometric designs that followed a similar pattern and form, and covered a man’s chest and back as well as other parts of the body.

Early documentation of indigenous tattoos in northern Luzon shows that the human body was fully tattooed with distinct and abstract patterns, as seen in the tattoos found on mummies in Kabayan, Benguet.

Most tattoo practitioners (mambabatok) in the past were men. Female tattoo practitioners were rare, as was the case of Whang-ud from Buscalan in Tinglayan, Kalinga.

There were two kinds of tattoo artists in the past: a resident tattoo artist who stayed in the village, and a traveling tattoo artist who visits communities to ply his trade. A tattoo artist can, however, be both.

The traditional tattoo was considered a painful rite of passage, a body decoration, a talisman against malevolent forces, a mark of bravery, a visible mark of religious and political affiliations in the community, and a symbol of status or affluence.

Batok is an inscription of culture on the body that can focus on religion, politics, warfare and rituals. They are also seen as a repository of stored memories, experiences and information. Tattoos record the biography of a person as well as the complex tradition of the community. It is a signifier of collective ethnic identity. —Analyn Salvador-Amores