Witness to the Supremo’s trial

The house where Katipunan leader Andres Bonifacio was tried for treason now stands as a memorial to his contributions to the Philippine Revolution

MARAGONDON, Cavite—Dimmed lights add to the gloomy atmosphere that shrouds the 128-year-old “Bahay na Bato” (colonial house), which became the stage to one of the darkest episodes of the Philippine Revolution.

On May 4, 1897, about a year before the declaration of Philippine Independence, 11 people gathered on the house’s second floor to hear the case against the “Supremo,” Andres Bonifacio. The leader of the Filipino revolutionaries and his brother Procopio were charged with plotting the assassination of the first Philippine President, Emilio Aguinaldo, and perpetrating hostilities in Limbon village in Indang town, Cavite.

The military court, headed by Gen. Mariano Noriel, found the Bonifacio siblings guilty of treason and recommended their execution.

Also known as the Bonifacio trial house, the two-story colonial structure has a floor area of about 80 square meters and was declared a national historical landmark by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) in 1997.

It used to be the ancestral home of Teodorico Reyes, who came from one of Maragondon’s prominent families. Not much has been written about the Reyeses’ ties to Bonifacio’s Katipunan, except that they were not home when the trial took place.

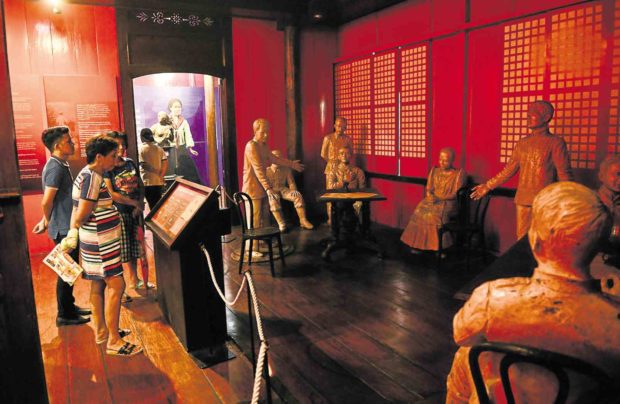

Article continues after this advertisementReyes’ descendants sold the property to a certain Jose Angeles sometime in the ’90s. The house was converted into a museum in 2000 and was “modernized” in 2014 to include an interactive life-sized diorama of the trial scene.

Article continues after this advertisementMuseum guide Jonel Rabusa said the events that took place in Maragondon were among the more “controversial” in Philippine history.

“What’s tragic was that [Bonifacio] founded the Katipunan only to die in the hands of his own people,” Rabusa said.

After the trial, the Bonifacio brothers were incarcerated in Maragondon Church for five days without Andres’ wife, Gregoria de Jesus, knowing where he was. On May 10, 1897, Filipino soldiers led by Maj. Lazaro Makapagal took the brothers up the mountains where they were killed.

THE PAST REVISITED Students listen closely to a museum guide as they relive history through an interactive diorama of Bonifacio’s trial.

2 versions of the execution

There were two versions of how the execution was carried out.

“Procopio allegedly tried to flee, prompting the soldiers to shoot him and Andres,” said Maragondon Mayor Rey Rillo. Aguinaldo supposedly wanted the sentence commuted but the president’s order came too late, he added.

The other version, Rabusa said, was that Andres was hacked to death and his body chopped up, which might be the grim origin of the childhood poem “Putol-putol” (known among kids as “A-tapang a-tao”).

In 1918, human bones were exhumed in Mt. Nagpatong here, where the NHCP later put up a memorial shrine for Bonifacio.

“Even with the bones recovered, some people questioned if they actually belonged to Andres. How come there was only one set [of bones]?” Rabusa said.

Cavite had been witness to many significant events throughout the revolution, including the rift between the Aguinaldo-led Magdalo and the Katipunan faction, Bonifacio’s Magdiwang.

At the Bonifacio trial house today, an electronic map shows that 12 Cavite towns were under Magdiwang, while 10, including the towns of Bayuyungan (now referred to as Laurel) and Talisay in Batangas province, belonged to the Magdalo.

Tejeros Convention

The tragic event that led to Bonifacio’s execution unfolded when the Magdiwang Council invited Bonifacio to Cavite for the 1897 Tejeros Convention, which was meant to unite the two rival councils into a central revolutionary government.

Despite his absence, Aguinaldo was elected president but with many of the votes coming from Bonifacio’s own faction.

“Cavite’s icon has always been Aguinaldo,” Rabusa explained.

Despite the shadow cast upon him by the trial and death of Bonifacio, Aguinaldo remains revered in Cavite, and it is at his ancestral home where the Philippine flag is unfurled every June 12 in a symbolic ceremony.

His home in Kawit is now known as the Aguinaldo Shrine.

Maragondon, the lesser-known town, meanwhile quietly commemorates history with a simple wreath-laying every May 10 and November 30, Bonifacio’s birthday.

“[Bonifacio] was killed here, but we did not kill him,” said Elvie Estrada, Maragondon’s municipal planning officer.

In fact, Maragondon’s two local heroes, siblings Emiliano and Mariano Riego de Dios, voted against Bonifacio’s execution.

Two museums

Bonifacio was born in Tondo, Manila, but ironically, none of the only two museums dedicated to him is located in the Philippine capital.

One of them is in Maragondon, and the other, Museo ng Katipunan, is in San Juan City.

“Nakapangingilabot (You get goosebumps),” Rillo said of the atmosphere inside the museum, especially whenever the audio recording recounting the trial proceedings played for museum guests.

“The Bonifacio trial house is not as popular [as other museums],” Rabusa admitted. “Many people still think this was Bonifacio’s house.”

Before it was modernized with an interactive diorama, the museum would have 1,000 guests at most every month, many of them students on educational trips.

The number has increased in recent years through word-of-mouth and social media posts.

George Garcia, 60, a Bukidnon resident who was visiting relatives here, said he never knew Bonifacio was put on trial for treason.

Rabusa lamented that Bonifacio’s trial was not as well-known as other historic events. But the museum here always strives to present history objectively based on evidence, he said.

Rillo said the trial was not something they took pride in, considering its tragic end. But they treat Bonifacio with equal importance just as they do other national heroes who fought for the country’s independence, he added.

Bonifacio may have met his end here, but Maragondon is making sure the hero gets a home where his contributions to the Philippine Revolution are immortalized.