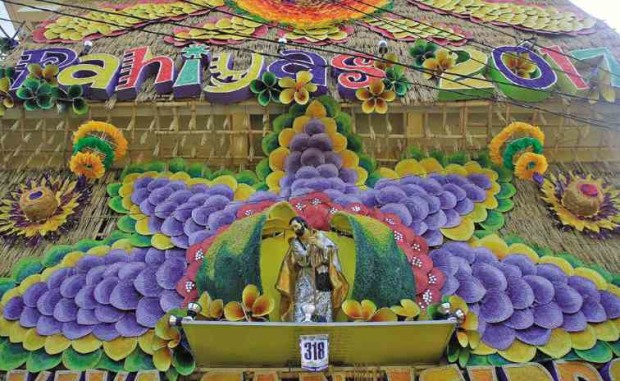

An assortment of multicolored “abaniko” (native hand-held fan), “kiping” (rice wafers) and palay stalks adorn one of the houses in Lucban, Quezon province, during the Pahiyas Festival, an annual thanksgiving for the town’s bountiful harvest. — DELFIN T. MALLARI JR.

LUCBAN, Quezon—As Pahiyas Festival visitors enjoy the displays of multicolored “kiping” (rice wafers), newly harvested fruits and vegetables, and native products that adorn houses here every May 15, they are unaware that the tradition behind the visual treat is dying.

Younger Lucbanin seem uninterested to continue the tradition of making kiping, the indigenous “arangya” (kiping chandeliers) and other homegrown products that have long been used as decorative items during the festival that honors San Isidro, the patron saint of farmers, according to local officials.

Dennis Jardin, Lucban tourism officer, said most young Lucbanin would rather spend time with their friends, surf the internet and interact through social media platforms.

“They really don’t have the interest. For the longest time, we’ve been convincing and motivating them to learn and continue the tradition because it’s ours,” Jardin said.

Bert Teope, 65, one of the town’s kiping makers, shared the same observation.

“Our youth have no interest in making kiping. If this continues, the tradition may soon end and our San Isidro (feast) will never be the same again,” he said.

Teope said even his two children were not showing an interest to learn the tedious process of making the colorful rice wafers, a Pahiyas trademark.

He sells a piece of leaf-shaped kiping for P7, lower than the P9-P10 in commercial outlets.

Teope said while older Lucban residents could make kiping, their production was limited and intended only for household decorations during Pahiyas.

“I’m getting old. Making a batch of kiping for 72 hours straight is really hard,” he said.

To save the dying practices in the town, the local government, led by Mayor Celso Olivier Dator has been sponsoring annual contests in producing kiping, “longganisa” (pork sausage) and native bags. Competitions on buntal weaving and arangya design are also held during the Pahiyas to promote the town’s culture and tradition.

Jardin, however, lamented that the same set of contestants, mostly older Lucbanin, would show up.

“We have no ‘millennial’ contestants,” he said.

He said Lucban’s own “pansit habhab” (also called pancit Lucban, a noodle dish served on banana leaf and best slurped, not eaten with utensils) was being claimed by neighboring towns as supposedly one of their original products.

“I’ve personally encountered such an episode and I immediately corrected [the information]. No one can deny that pansit habhab is Lucban’s very own,” Jardin said.

“Without safeguarding what we have and our day-to-day way of life, I’m afraid we would eventually lose our identity as Lucbanin,” he said.

Teope observed that some residents would only decorate their houses due to prizes offered by festival organizers.

“It’s no longer because they want to thank San Isidro for a bountiful harvest,” he said.

But Jardin said they were not giving up on Lucban’s youth, noting that several of them support the Maytime tradition.

Among them is designer Jake Peralta, 20, grand winner of last year’s “Parikitan” contests, featuring gown and barong designs using indigenous materials, like coconut fiber.

“I’m doing my own share in helping my town to continue our artistic tradition,” Peralta said.

According to Jardin, the town is starting to train a younger set of artists and talents.

“If we want to pass the torch to the next generation, we have to start early,” he said.