Kids arrested, abused in war on illegal drugs

(Last of two parts)

Under pressure to show they are winning the fight against narcotics, police are raiding alleged drug dens with increasing frequency.

But among those regularly picked up are children, who are sometimes manhandled the same way adult criminals are.

A police manual revised in October last year prohibits physically harming children in conflict with the law or children at risk, said Chief Insp. Maimona Macasasa, spokesperson for the Philippine National Police Women and Children’s Protection Unit.

It is possible, however, that “some policemen abuse [and] hurt children,” Macasasa said. “If this is true, we will file administrative cases or criminal cases against the policemen,” she added.

Article continues after this advertisement‘Rescued individuals’

Article continues after this advertisementChildren caught breaking laws are “rescued individuals,” not criminals, Macasasa said. Under the guidelines, they should be turned over to social workers within eight hours of their arrest.

“They should not be detained, [or photographed], or even handcuffed,” she said.

But that’s only on paper.

Angelo, 15, knows the beatings firsthand.

An orphan, he had mastered the system after he was taken in by social workers in 2012.

He was first taken in after a neighbor charged him with frustrated homicide for stabbing her with a pen, and then for stealing a mobile phone.

From petty theft, he graduated to drugs, he said.

He said he ignored a warning by a friendly policeman to stop, but last December he was roughed up.

The policeman picked him out of a crowd, pulled a plastic bag over his head and punched him several times.

Old story

Then the policeman told the teenager to run. He refused, he said. “I know that story already. They will make me run, then shoot me.”

Angelo said he was detained, his head shaved, and he was charged with possession of illegal drugs after the cops allegedly found “shabu” (crystal meth) on him.

He denied the charge but did not dare complain for fear of meeting the same fate that befell a 19-year-old friend.

“He was killed in ‘Tokhang,’” he said, referring to the PNP door-to-door campaign to persuade drug users and pushers to surrender, which has become synonymous with police sweeps where drug suspects are shot dead after allegedly fighting back.

Five days after he was arrested, Angelo was turned over to social workers.

“I am angry with the police because I was not able to spend my birthday with my family. It’s quite hard here. Very lonely,” he told the Inquirer.

“People don’t believe I can change. I am not sure, but I will never return here,” he said.

Minors detained

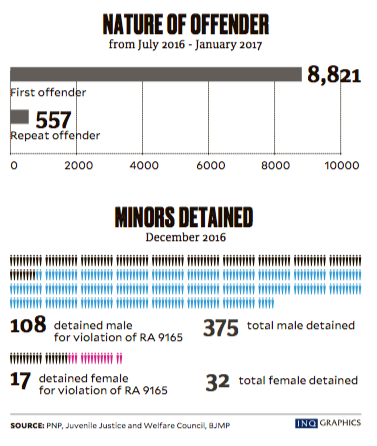

Director Serafin Barretto of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) said 407 minors were detained nationwide because the courts were still validating their age.

“Some of them fake their age to make themselves younger so they can escape criminal liability. Other innocent children who want to escape [from social welfare centers] pretend to be older so they will be put in regular jails,” he added.

According to BJMP data for January 2017, jails nationwide were 555 percent crowded, an increase from 400 percent before President Duterte’s war on drugs.

The jails were holding 128,869 inmates, 61 percent of whose cases involve illegal drugs. Among them are 125 children detained for various drug offenses, Barretto said.

The true age of children can be verified through dental examination and their birth certificates, and a court order can save them from jail.

“But not all jails can seclude the ‘minors.’ Most often, they are mixed with the others and are given the same interventions,” Barretto said.

He said he opposed moves in Congress to lower the age of criminal liability, stressing that children would find it difficult to adapt to the violent world of detention.

“The jail opens children to the idea that drugs could be a bigger illegal trade inside the prison,” he said. “If before they were mere drug runners, now they realize there’s more money in drugs.”

Macasasa said that despite the new manual on children, there remained a lack of coordination with the social welfare department.

But should Congress pass legislation lowering the age of criminal responsibility to 9, support services for the kids would be gone, too, she said.

Crimes committed by minors

Data from the PNP show that 2 percent of crimes nationwide are committed by minors.

According to records at the PNP Women and Children Protection Unit, 973 children nationwide were charged with various drug offenses from January to December last year. About 106 of them were caught sniffing rugby or industrial glue.

The highest incidents were recorded in Bicol with 372; Eastern Visayas, 150; and Calabarzon (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, Quezon), 110. Metro Manila had 11 cases.

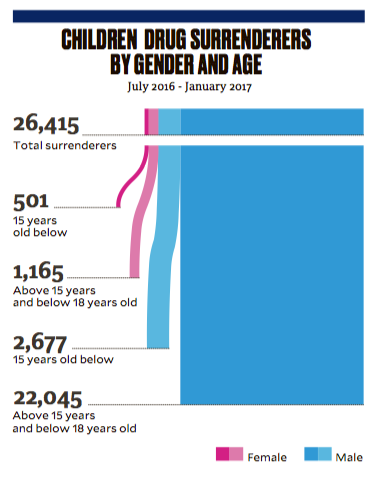

Since the launch of the war on drugs in July last year up to January this year, 26,415 children had surrendered under Oplan Tokhang, with the bulk coming from Central Visayas (4,841) and Northern Mindanao (4,676). Manila placed sixth with 1,309.

Of the 26,415 people who had surrendered since January, 3,178 were under 15 years old, while 23,237 were between 15 and 18.

Surprisingly, most of them were either high school students, dropouts or still in elementary school.

The Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center said more than 30 minors were killed during the same period.

Among them were high school student Emmanuel Lorica, who was shot last year while sleeping inside an evacuation center in Pasig City, and Danica May Garcia, 5, who was hit when two gunmen fired at their home in Dagupan City while hunting her grandfather, who managed to escape.

Jayson’s case

Adding to the problem was the absence of data on children involved in drugs when the campaign began last year. For instance, there were no exact figures to show increasing drug dependence rate among children.

The body of Jayson, 16, was found inside a sack that was dumped in Barangay Commonwealth in Quezon City last year. His body bore multiple stab wounds.

His killing has remained unsolved, but officials have managed to piece together details of his troubled life.

A month before his death, Jayson was taken in by officials in nearby Barangay Batasan, where he had identified himself as Michael Jayson Diaz. He had promised not to break any more laws after being caught five times for theft and other offenses.

Rosalinda Gabriel, a barangay official, said Jayson was brought to her office for theft for the first time in 2014, when the then 13-year-old repeatedly declared: “I’m a child! I have a birth certificate! I know my rights!”

Jayson was born on Christmas Day in 1999. But until his last case, he would write down his age as 13.

Gabriel said the barangay council would keep Jayson in its office and feed him, but he would always escape.

Officials said that under current laws, Jayson could not be jailed or tried as an adult. After being kept in a youth center for more than a month, he was turned over to his guardians.

Restorative justice

The BJMP’s Barretto said the Philippines still lagged behind other countries in restorative justice and programs for the reintegration of child offenders into society.

Jayson’s stepmother, Miriam Diaz, heard about his fate from the barangay, which directed the family to a funeral home in Quezon City.

“And then we found out that he was stabbed with an ice pick—16 times—in his head, in his neck, in his chest,” said Jayson’s grandmother, Anita.

Miriam and Anita said Jayson used illegal drugs and worked as a drug runner. He would often go to Salaam Compound in Barangay Culiat where shabu was marketed.

The family’s hand-to-mouth existence and the breakup of his parents’ marriage could be partly blamed for Jayson’s troubles, which ended in a death he certainly did not deserve.

When Miriam and Anita arrived at the funeral home on June 4, they were shown shocking photographs of Jayson’s body. They felt his pain but could do nothing but hope other children would not suffer the same fate.