Drug war doesn’t spare even the young

CHILDREN’S RIGHTS Kids join advocates of children’s rights in denouncing the killings of minors as the Duterte administration launches anew a bloody crackdown on illegal drugs. —MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

(First of two parts)

When Rodrigo Duterte came to power last year, he launched a brutal war on illegal drugs. But more than 8,000 deaths later, the stories of children caught in the web of daily violence stand out as a sobering reminder that the menace cannot be stopped by bullets alone.

Matthew learned it the hard way. At 13, he is a veteran of Manila’s mean streets, having quit school four years earlier to peddle crystal meth, or “shabu,” with his friends.

He earned a third for every sale he made—as much as P200 in commission, or about half of the average daily wage in Manila—cautiously ignoring a public threat by President Duterte that he would kill drug pushers and addicts, and dump their bodies in Manila Bay for the fish to eat.

Last August, a month after Mr. Duterte took office, Matthew was picked up by police officers, beaten and shot. But he survived to tell his story.

“They would have killed him,” said a social worker at a city social welfare and development center who took him in. “Had he not been that strong, he would have died. That pains us.”

The Inquirer is withholding the center’s name and Matthew’s real identity to protect them from reprisal. The facility prepares children in conflict with the law for reintegration into society.

Terrible ordeal

Describing his terrible ordeal in the hands of police, Matthew said he was kept in jail for days.

“They arrested me. The police officer told me to run, so I ran very fast. I thought he was letting me go. But he shot me. I was knocked out,” he said.

When he came to, he said, he was in the police vehicle and saw his mother trying to come near him. “The cop pinned my head with his foot and threatened to shoot my mother if I would not tell her to leave,” he said.

Matthew said he was being filmed as he writhed in pain.

He was turned over to the police station’s narcotics unit, where he was held for several days. “I know what I did was wrong. But I still don’t understand why he shot me,” he said.

Matthew was healing fast at the city social welfare center.

The boy said he peddled drugs to survive, using his earnings to buy clothes and food for his family. He lives with his 73-year-old grandfather, a delivery man, and an uncle who is mentally ill.

His father, a drug user, is in hiding, social workers said.

Matthew said he had been selling drugs for three months, but refused to divulge his source. “The members of my group are also my friends, and they give me food. We are happy together,” he said.

“Two of my friends were killed by policemen. I was frightened, too,” he said.

A companion, who was arrested with him, was also shot and wounded. He is being held in a jail in another city.

The police investigator in Matthew’s case said the boy was arrested with an adult man.

Contradicting Matthew’s statement, the investigator said the boy was accidentally shot when his companion tried to escape and grabbed an officer’s gun. The man was subdued and detained.

Matthew was detained for five days as he recuperated, while the older suspect was detained for more than 10 days with a bullet in his buttocks.

The Manila police station said four other minors had been killed since Matthew was taken in, mostly by unidentified gunmen.

A 17-year-old suspected drug pusher was also shot dead in a gunfight with police.

‘A dead pig’

Six other children, including a toddler, were wounded when suspected vigilantes targeted a victim.

As Matthew is a minor, no case was filed against him.

“The place outside is not safe for children like him,” his shelter parent said.

Sixteen-year-old Michael Jayson Diaz was not as lucky as Matthew.

On a Saturday morning last June, village security volunteer Lourdes Luna was alerted to a sack dumped near her home at Barangay Commonwealth in suburban Quezon City.

“I gave it a kick and blood oozed out of it,” said Luna, 58, who arrived at the scene with another volunteer. “I immediately thought it was a dead pig.”

The two decided to slash the sack open and were shocked to find the body of a boy inside.

Ironically, a blue baller on the boy’s ankle bore the name of Mr. Duterte, who campaigned on an anticrime platform.

The boy was hogtied and his slender body was bent all the way back so that his head almost touched his feet. His body bore multiple stab wounds.

Crime scene investigators arrived and asked the usual questions.

No one claimed the body.

While President Duterte was still weeks away from officially assuming power, the boy’s death was a clear indication he was intent on keeping his campaign pledge.

Nida Curitana, of the barangay council’s women and children desk, later recognized the body as that of Jayson, who was frequently caught for theft and for breaking the 10 p.m. curfew in the area.

Under the Child and Youth Welfare Code, the Barangay Council for the Protection of Children (BCPC) is tasked with caring for the children.

Jayson was an out-of-school youth from Batasan Hills, said Mercy Aloro, a spokesperson for BCPC-Commonwealth.

As he was not a resident of Commonwealth, the village had no jurisdiction over him and the council let him go whenever he was caught.

The social workers said Jayson was often seen with three other minors who worked as scavengers at night but were known also as runners for drug sellers in a nearby area.

Common stories

Sadly, stories of poor children in the drug trade have become common. Pushers and traffickers use children because they know that under current laws, minors cannot be prosecuted.

Aloro said a recent case she handled involved an 11-year-old shabu user, who was used as a runner by local drug pushers.

The boy was arrested and detained for several days, like Matthew, but the court later ordered the police to free him.

“The court asked us, ‘What are you going to do with the child?’” Aloro said. “We had only one answer—you cannot send him back to his community. Why? First, it’s dangerous for the kid, he’s already at risk. He could get killed. Pull out the child, that was our recommendation. So his parents sent him to Bicol.”

According to studies, the high drug affectation rate in densely populated areas of Quezon City has contributed to the spread of illegal drugs. This is the same problem in poor communities in Manila, including the slums of Pasay and Tondo districts.

The Quezon City police listed 160 children among those who surrendered for drug offenses from June 2016 last year to Feb. 5.

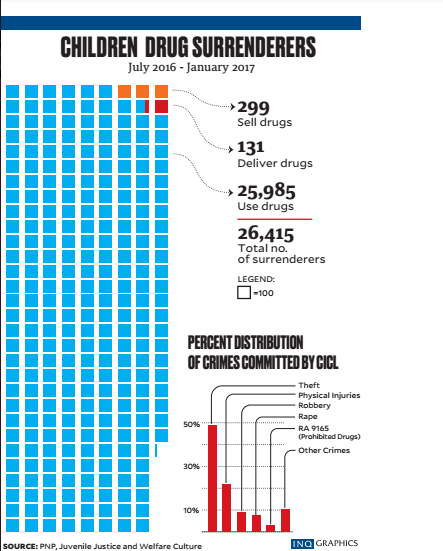

Nationwide, the Philippine National Police recorded 26,415 children among those who surrendered for drug offenses from July 2016 to January 2017. More than 800,000 turned themselves in during that period.

The majority of those who surrendered were drug users; 131 were arrested for delivering and 299 for selling drugs.

Community leaders say the drug problem has become rampant, but perennial lack of funds and trained personnel are weighing down antidrug programs.

Current laws require local government units to set aside just one percent of their internal revenue allotment (IRA) for local councils for the protection of children. And community social workers need more training on “restorative justice,” according to the Humanitarian Legal Assistance Foundation.

While village social workers were already good in counseling, they have yet to learn other procedures, such as determining children’s level of addiction, the foundation said.

Barangay Commonwealth, for instance, is set to launch this year a pioneering drug rehabilitation program for children, with 100 kids as the first participants.

It was, however, too late for Jayson. The single-page spot report on his death has been shelved in a stockroom in the community hall.

No one has been prosecuted for his murder, a cold case that serves as a cautionary tale for parents and their children in highly vulnerable, impoverished communities.