Radyo Bandido days recalled

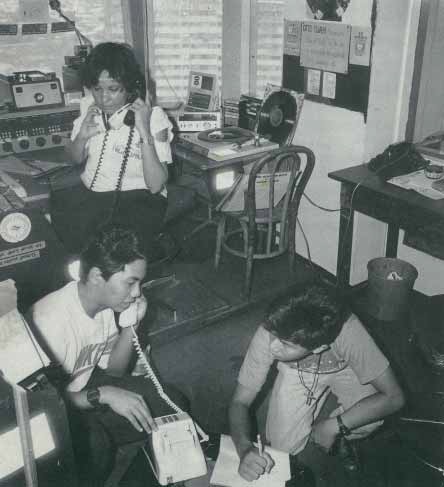

Actor Gabe Mercado (below) was only 13 years old when he and his elder brother Paulo (above) joined the staff of Radyo Bandido with June Keithley during the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution in this photo that appeared in the book “People Power.”

On Feb. 24, 1986, three days into the protests, dictator Ferdinand Marcos refused to leave Malacañang. People feared for their lives as orders to quash the growing protests, including an all-out attack on Edsa where they converged, became imminent.

Amid the chaos, Mercado, then 13, collated political and military information from a network of volunteers. The information was relayed to broadcaster June Keithley, who rallied her listeners to remain hopeful even under threat.

For 14 hours, Mercado, his 15-year-old brother Paulo and Keithley manned Radyo Bandido, which replaced Church-run Radio Veritas after it was shut down by Marcos troops. The trio was part of a volunteer network of theater actors under Jesuit priest James B. Reuter.

A rebel radio station was no place for two young boys, but the thought hardly crossed Gabe Mercado’s mind, the youngest volunteer on one of the most dangerous assignments.

Political consciousness

It wasn’t just bravery or foolhardiness that brought him there. Born in December 1972, Gabe Mercado was an unusually curious kid.

His consciousness was further shaped by his becoming an actor under Reuter’s wing when he was a grade schooler at Southridge School in Muntinlupa City.

Reuter’s theater group often toured nationwide, allowing Mercado to see startling differences between Manila and poverty-stricken provinces.

As with most people, Mercado’s turning point was former Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr.’s assassination on Aug. 21, 1983. The murder triggered massive protests against the Marcos regime.

Dangerous assignment

Amid the protests, the dictator called a snap presidential election that pitted him on

Feb. 7, 1986, against Cory Aquino, widow of the assassinated opposition senator.

Reuter activated his network of theater actors to report on the snap election, which was marred by massive fraud.

When their plot to oust Marcos was uncovered, then Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and his men holed themselves up at Camp Aguinaldo. The Armed Forces vice chief of staff, then Lt. Gen. Fidel Ramos, defected on Feb. 22. The two then asked Reuter and Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin to go on the air on Radio Veritas and implore the people to go to Edsa.

Armed men soon shut down Radio Veritas, prompting Keithley and the Mercado brothers to transfer to the dzRJ facility in Sta. Mesa, Manila. They resumed broadcasting and took the name Radyo Bandido by midnight of Feb. 23.

It was a frightening 14-hour duty. In between gathering reports and buoying people’s spirits, they planned out escapes in case of discovery. Not once, however, did the boys think about going home.

“My parents had heard over the radio that they were targeting the source of the rebel broadcast,” Mercado recalled. “They didn’t know where we were. They just knew Reuter. So they called him and said they would like their sons back.”

But Reuter did not budge, the actor said. “He told my parents, ‘They have a chance to die as heroes. Why would you take that away from them?’”

‘Reuter babies’

Though it was Keithley who was eventually recognized as the “voice of Edsa,” the Mercado brothers and the rest of Reuter’s actor-reporters were instrumental in keeping the people informed during the revolution.

Now 44, Mercado remains an actor, as do most of the other “Reuter babies.” He founded Silly People’s Improv Theater, or Spit Manila, the country’s premiere improv group renowned for its incisive brand of comedy.

He hoped to contribute to an arts movement that “raises awareness, reframes our values and the conversations on what is happening in the country.”

He recalled the wave of relief and victory that swept the nation when Marcos and his family fled the Philippines on Feb. 25, 1986.

Has Edsa lost its magic amid the threat of a Marcos resurgence?

“My friend Gang [Badoy] once said the Edsa revolution was like a grand wedding, except we didn’t work much on the marriage. We didn’t bother much on what would make it work: governance, public policy, on being truly inclusive,” Mercado said.

Yet the marriage was not without hope. He said the youth must fight for “real knowledge and real facts,” and rise to the occasion against revisionism. —WITH A REPORT FROM INQUIRER RESEARCH