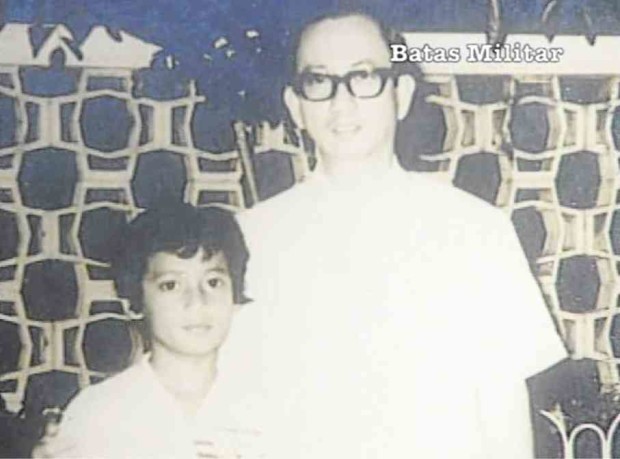

SINS OF THE FATHER Primitivo Mijares’ tell-all book on the Marcoses led to his disappearance and to the torture and death of his son Boyet. —VIDEO GRAB FROM BATAS MILITAR DOCUMENTARY

Joseph Christopher “JC” Mijares-Gurango knew very little about his grandfather, Primitivo “Tibo” Mijares. Unlike other kids whom elders would regale with tales about their grandfathers’ exploits, JC never heard a word about such from his mother, Dr. Pilita Mijares-Gurango, nor from his grandmother, retired trial court judge Priscilla Mijares.

There was no word, too, at the family dinner table about his uncle, Luis Manuel or Boyet, the Mijares’ youngest son, or why he was no longer with them. Except in one instance.

“I was about 13,” JC recalled. “My mother was being overprotective, and it annoyed me. So she told me that she had a brother who was kidnapped,” he added.

But Pilita, a craniofacial surgeon for children, didn’t say much after that brief explanation.

The truth about the fate of his Lolo Tibo and Tito Boyet would come about two years later “(when) my lola dropped off a big stack of copies of the book, ‘The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos.’ She told me it was written by my Lolo Tibo. I read it but everything just went over my head,” JC said.

“I got to properly read it again a couple of years ago and it was then that I really understood what my lolo had wanted to say,” he continued. Then he remembered the “kidnapping” that his mother never wanted to talk about. “I sort of connected the dots,” JC said.

Disappeared

“I never talked about it. I chose to forget,” Pilita explained.

She said the silence started with her mother who insulated them from all the stories that swirled around following Mijares’ testimony before the US Congress in 1975, about the abuses of the Marcos regime.

Mijares, a former National Press Club president who became a trusted aide of the late dictator, had written an insider’s account of the Marcoses’ excesses in the book, “Conjugal Dictatorship…” and disappeared soon after its publication.

“My mother did not talk about it,” Pilita said.

The Mijares couple have four children: Perla, Jose Antonio, Pilita and Luis Manuel. The girls were sent to St. Theresa’s College and the boys, to Lourdes School, both in Quezon City. They lived in Project 6, Quezon City, on a street where other newsmen lived.

Pilita said the family used to go to the National Press Club to watch some shows, but that was all they knew about their father’s work. When Mijares joined the Marcos government as a propagandist, his kids started teasing him about being a “Marcos tuta” (Marcos lapdog), Mijares himself would write in his book.

When Mijares “disappeared,” and rumors buzzed about him being thrown out from a helicopter by Marcos’ henchmen, Pilita and her siblings continued to hope that he was just in hiding somewhere. Then came Boyet’s kidnapping a few months after, in 1977.

“Maybe we were just paranoid but after the second strike, you can’t blame us for being fearful,” Pilita said.

In fact, the brutal fate of the young Mijares makes for such painful reading that one can understand the family’s desire to totally blot out its memory.

But even more heartbreaking than the description of the boy’s mangled body was Judge Mijares’ quote from the report she had filed as one of Claimants 1081, a group of martial law victims seeking compensation from the Marcoses.

Phone pal

According to “Marcos Martial Law: Never Again,” Raissa Robles’ book on that dark era, the judge had obtained a lot of information that “during the torture of my son, the father was made to appear by the torturers to witness his son’s agony.”

In an interview for the documentary “Batas Militar: Martial Law in the Philippines in the 1980s,” Mijares said she would later be told that Boyet had a phone pal whom he went out to meet on the day he disappeared.

The young Mijares’ body was found two weeks later. “He was tortured brutally, with all his nails pulled and removed. He had 33 ice pick wounds around his body,” Judge Mijares said in the Batas Militar docu, which was first aired on the 25th year of martial law declaration in September 1997.

“We waited for two weeks for the ransom call,” Pilita said. The supposed kidnappers had initially asked for a P200,000-ransom. “But my mother was able to raise only P20,000. We were ready to pay, but the call never came,” she recalled.

The supposed kidnappers had introduced themselves to the Mijares family as the Bangsa Moro Army. At one point, Pilita said, she asked to hear the voice of her brother, but the supposed kidnapper replied: “We cannot do that, but we can send you his ear.”

“My mother broke down,” Pilita said. After two weeks, Judge Mijares went public with her son’s kidnapping. The family also sought help from Col. Rolando Abadilla of the much feared Military Intelligence and Security Group, who sent out a team of investigators to rescue Boyet and bodyguards to secure the other Mijares children.

“We asked for (their) help, so we listened to them. They told us about a call that was traced to a pavilion at UP. So we were scared,” Pilita said. At that time, she and siblings Perla and Jose Antonio were all in college at the state university.

Panfilo Lacson

The team assigned to the Mijares family was led by a young Metrocom officer named Panfilo Lacson. “Lacson was the boss of our guards. He would show up in our house, talk to mom and feed her information,” Pilita said.

It was Lacson who told their mother that Boyet, who had just finished junior high school at Lourdes School, was being recruited by a fraternity. “He told mom about a call that was traced to a Romeo Abodie who agreed to turn state witness,” Pilita said. The Mijares family relied on Lacson’s reports. “We did not have other sources, we were living in fear,” Pilita recalled.

The battered body of the young Mijares was found two weeks after he disappeared. It turned out he was killed on the night he disappeared. The ransom call was merely a bluff, Pilita said.

But the Mijares family was even more surprised to hear tapes of Boyet’s phone conversations with the supposed kidnappers.

“We realized our phone had been tapped all along,” she said.

The realization that their father, who was last seen at the Guam airport leaving for Manila, was never coming home slowly sank in during the two-year trial of Boyet’s case. Three young frat men were convicted, but according to reports, one of them died in prison, while the two others had escaped.

The Mijares family’s hopes that their patriarch was just in hiding were dashed when he did not surface even after Marcos’ ouster in February 1986.

Opposition figures Raul Manglapus and Heherson Alvarez came home from US exile when the Marcoses were ousted, but Mijares was never heard from again.