Fossil shows evidence of live birth of ancient reptile

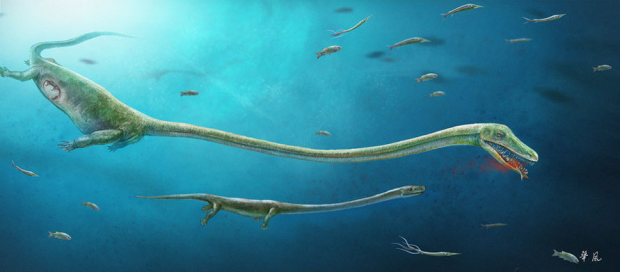

Artist’s reconstruction of Dinocephalosaurus showing the rough position of the embryo within the mother. Image from Nature Communications journal.

An unusually long-necked marine reptile gave birth to live young 245 million years ago — the only known member of the dinosaur, bird and croc family to not lay eggs, researchers said Tuesday.

Archaeologists examining the fossil of a female Dinocephalosaurus from Yunnan Province, southwest China, were amazed to discover the remains of a baby among the bones where her abdomen would have been.

“I was so excited when I first saw this embryonic specimen,” said Jun Liu of China’s Hefei University of Technology who co-authored a study published in Nature Communications.

“This discovery rewrites our understanding of the evolution of reproductive systems.”

Dinocephalosaurus was a member of the archosaur family, which includes extinct dinosaurs as well as today’s birds and crocodiles — all egg-layers.

The archosaurs’ sister clade of turtles also lays eggs, but a third group of reptiles called lepidosaurs, including lizards and snakes, contains some species that give birth to live young — including some sea snakes, boas, skinks and slow worms.

Live birth is usually associated with mammals, and egg-laying is considered the original, “primitive” state of animals.

Dinocephalosaurus was a strange-looking ocean-dweller with a neck almost twice the length of its trunk — some 3 to 4 meters (10-13 feet) in total.

It was a fish eater, snaking its long neck from side to side to catch prey.

The baby Dinocephalosaurus, or what remained of it, was about a tenth of the mother’s size.

Offspring or lunch?

At first, “I was not sure if the embryonic specimen (was) the last lunch of the mother, or its unborn baby,” Liu told AFP by email.

“Upon closer inspection and searching the literature, I realised that something unusual has been discovered” — an embryo providing “clear evidence for live birth”.

Unlike prey, which would ordinarily have been swallowed head-first, the young Dinocephalosaurus was facing forward in the abdominal cavity, said Liu.

The scientists also discounted the possibility that the tiny reptile had been inside an egg shell which simply eroded over time.

The specimen “demonstrates the curled posture typical for vertebrate embryos,” and there were no calcified shell bits found, said Liu.

Archosaurs are known to lay their eggs at a much earlier developmental stage, he added — long before the tot had grown to this size.

The new study pushes fossil evidence for the reproductive biology of archosaurs back by 50 million years, to the Middle Triassic, said the study.