Nearly 7 years after quake, 50,000 in Haiti still in camps

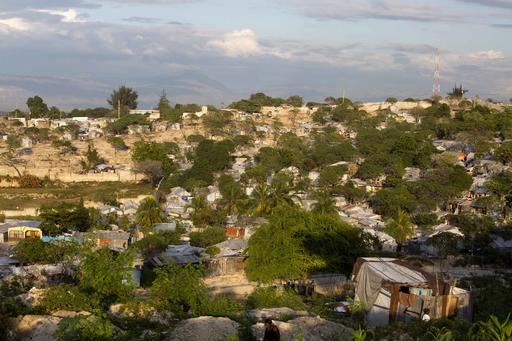

This Dec. 5, 2016 photo shows the hillside Delmas tent camp set up nearly seven years ago for people displaced by the 2010 earthquake, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The number of people in these makeshift communities has declined since the aftermath, but those who remain are a stubborn reminder that this impoverished country has yet to fully recover. AP

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti — Nearly seven years ago, Adrienne St. Fume and her family fled their home as the earth shook and their city crumbled around them. They ended up in what was then a vacant lot overlooking a cluster of shops along a busy street in the Haitian capital — and they’ve been there ever since.

The mother of three said she figured their plywood shack would be temporary as they and the rest of Port-au-Prince recovered from the January 2010 earthquake. But St. Fume has yet to find a way out.

“It’s been hard but we’ve tried our best to make a kind of life here,” she said.

At least 50,000 people like St. Fume remain in 31 settlement camps that emerged in Haiti in the days and weeks after the disaster. The number of people in these makeshift communities has declined 96 percent since the immediate aftermath, but those who remain are a stubborn reminder that this impoverished country has yet to fully recover from one of the worst natural disasters in history.

Authorities estimated 1.5 million people were living in more than 1,500 camps in July 2010. The numbers dropped either because people were evicted by private property owners, raised enough money to rebuild homes, or received rental subsidies from the government and aid groups that got them back on their feet.

Article continues after this advertisementThe International Organization for Migration, which is working with a final $7 million to resettle displaced people from three camps in Port-au-Prince, will soon be out of money for the effort, said Fabien Sambussy, the organization’s operations chief in Haiti. Even if the agency had more cash, it would still be hard to find housing for people in a country where more than half the population survives on less than $2 a day and adequate housing is increasingly expensive.

Article continues after this advertisementAnd there are those who don’t want to leave camps that in many cases morphed into crowded shantytowns.

“It’s quite difficult to try to convince them that they are not at home after six years,” said Sambussy, who said her agency has tried to clear out the camps in a humane way after forced evictions by people claiming ownership of the land became common during the first years after the quake.

St. Fume, who earns a meager living selling charcoal, said that unlike some of her neighbors, she would not oppose plans to move with her husband and their three children to subsidized housing for a year. They have struggled in the camp, where the mother said she dreams of living in a “decent house” where her children are safe.

“There’s always a lot of worry here,” she said on a recent morning.

In an area near the airport known as Tabarre, people in another camp said they have few prospects of permanent housing elsewhere and reject authorities’ proposals to move them into one-year rentals.

In this Dec. 5, 2016 photo, children sit on a parked car in the Delmas tent camp set up nearly seven years ago for people displaced by the 2010 earthquake, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The number of people in these makeshift communities has declined since the immediate aftermath, but those who remain are a stubborn reminder that this impoverished country has yet to fully recover from one of the worst natural disasters in history. AP

“We took over this land. This place is home now and we want it to be considered our own village,” said Wilson Mathieu, a grandfather who built a concrete general store in the dusty camp filled with roadside vendors and tiny lottery shops.

The rental subsidies initiative has been a shortsighted approach to empty the camps but it hasn’t been accompanied by more sustainable housing policies in the hemisphere’s poorest country, said Robin Guittard, who oversees Caribbean campaigns at Amnesty International.

“Between the levels of money pledged to Haiti after the earthquake in 2010 and the housing reality today, it has been clearly an unsuccessful story for both the Haitian authorities and the international community,” Guittard said.

Haiti’s severe housing shortage has meant that many displaced Haitians have had no option but to move into the overcrowded homes of relatives or construct precarious shacks in hillside slums, particularly an unregulated sprawl called Canaan outside of Port-au-Prince where at least 250,000 people have settled.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

Haitian and international officials had hoped to use Port-au-Prince’s devastation to build an improved capital and decentralize the country. The idea was to use the quake as an opportunity to fix some of Haiti’s long-standing problems, housing at the top of the list.

But mass projects to construct permanent homes never materialized and a flood of international aid workers left after several years. While a number of camps once benefited from various relief programs, it’s been since 2014 that there’s been any aid that wasn’t linked to trying to swat down a crisis such as cholera outbreaks.

St. Fume says she has lost faith that her life will ever improve much.

“All I know is that the state doesn’t really care about us. If they did, they would have done something by now,” she said inside her wooden shack, its walls decorated with political posters for an unsuccessful presidential candidate given out at a rally. TVJ