MANSALAY, Oriental Mindoro—A monthlong sea journey from Holland (The Netherlands) was how fate brought anthropologist Antoon Postma to Oriental Mindoro province in the Philippines, where he found love and home.

Postma spent 50 years in the village of Panaytayan in Mansalay town with the Mangyan Hanunuo, documenting 10,000 photographs, artifacts and materials on the life and culture of the indigenous peoples.

“If not for him, I would not know how rich our culture is,” said Unyo Insik, Panaytayan village chief.

As a sign of respect, the Mangyan people addressed Postma as “Bapa,” their term for uncle. His work inspired the celebration of Mangyan Day during the village fiesta.

Postma, a Catholic missionary, came face-to-face with the Mangyan in the early 1960s. He was immediately captivated by the beauty and richness of their culture.

Fr. Ewald Dinter, SVD, his coworker for 30 years in the Mangyan Mission, said Postma documented over 20,000 Mangyan poems, locally called “ambahan.” These were recorded, digitalized and preserved at Mangyan Heritage Center (MHC), which Postma cofounded, in the City of Calapan.

Defender

“He defended the Mangyan from abusive soldiers during martial law and from land grabbers,” Insik said.

Baptized Antoon Vreez, Postma was born on March 28, 1929, in Enkhuizen, The Netherlands. He had been a permanent resident of the Philippines since April 1958.

From 1952 to 1989, he was a member of the Society of the Divine Word (SVD), an international missionary community, and served in the towns of Roxas, Pinamalayan and Mansalay.

“He was strict and believed that the way to empower the Mangyan and to lift them is to educate them,” said Leslie Macuha, an instructor at Clarendon College and Postma’s assistant when he produced “Annotated Mangyan Bibliography: 1570-1988.”

Indigenous schools

Postma put up the first public elementary school for Mangyan in Mansalay and founded a Catholic high school, which was later named Sacred Heart Academy, in Gloria town and another school in Mansalay.

“He convinced me to join him as he started almost by himself. Thousands have graduated, many have become professionals,” said Adelita Sucgang, 89, a retired judge. Now, there are Mangyan nurses, midwives, teachers, a lawyer, a priest and a nun.

Postma was vicar general of Mangyan Apostolate in Mindoro (1968-1986), Mindoro representative to the Episcopal Commission on Tribal Filipinos (1978-1986), and archivist, statistician and historian for the Apostolic Vicariate of Calapan (1979-1985).

Legacy

“His involvement with the episcopal has contributed to the nationwide mainstreaming of the Department of Education (DepEd) on Indigenous Peoples (IP) Education Framework (DepEd Order No. 62),” said Mariel Andrea Gardiola, a student of anthropology.

“There are mainstream schools in Mindoro and Palawan which use the IP curriculum, which teaches Surat Mangyan/baybayin in their schools,” Gardiola noted. “Several myths, like the Mangyan have tails, is becoming a thing of the past.”

Among Postma’s published books are “Vocabulario Tagalo” (Old Tagalog-Spanish Dictionary collated from unpublished Manuscript Documents in 2000), Ambahan Mangyan (w. syllabic Mangyan script in 1989); “Mangyan Encounters” (1985); “Mindoro Mangyan Mission” (1981); “Treasure of a Minority” (1981), which covers a person’s life cycle from birth to grave; and the four-volume “Kultura Mangyan” (2005) on the life, culture and history of the Mangyan in Filipino and Hanunuo languages.

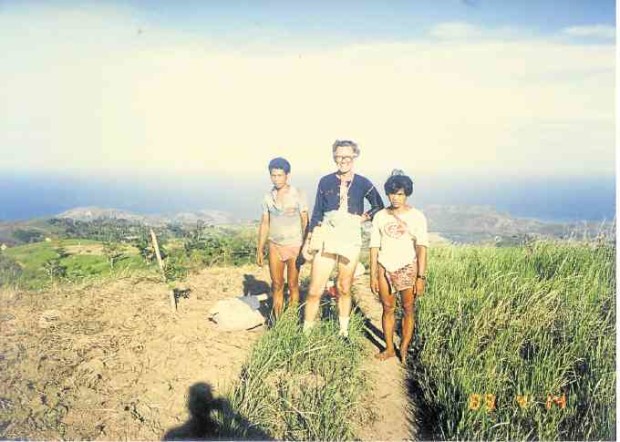

Postma valued education and supported schools for the indigenous peoples of Mindoro Island. At left is Postma with his wife and children. —PHOTOS COURTESY OF MANGYAN HERITAGE CENTER

Due largely to his efforts, the two Mindoro paleographies of the Hanunuo-Mangyan and the Northern Buid, and the paleographies of the Tagbanua and Palaw’an of Palawan, were declared National Cultural Treasures and are inscribed in the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) Memory of the World Register.

“His comprehensive collection of valuable documents are being used and referred to by the Mangyan in proving that they are the original settlers in Mindoro,” said Emily Catapang, director of MHC. She cited Postma’s complete collection of proclamations of reservations.

“His documentation of their cultural practices that are no longer widely practiced are being revived now like weaving, clothing, handicrafts and bead works,” Catapang said.

“Postma planted the seed that kept alive the rich Mangyan cultural practices, specifically the Mangyan syllabic scripts and the ambahan. The challenge to the present and future generations of Mangyan is to nurture what Postma started,” she added.

Last respects

On Oct. 22, Postma succumbed to kidney and heart failure, leaving behind his Mangyan wife, Yam-ay Insik, and children Anya, Sagangsang, Yangan, Ambay and grandchildren. He was 87.

Postma would have wanted to be buried at once, wrapped in a native mat, blanket and bamboo like a Mangyan. But this plan did not push through as he had to be transported back to the mountain.

Mangyan people, local officials, members of the SVD community and friends, including anthropologist Dr. Masaru Miyamoto, who flew from Japan, paid their last respects before he was buried on Oct. 25.

The Sangguniang Panlalawigan passed a resolution recognizing his contributions.

A number of agencies have expressed interest in preserving Postma’s work, including putting them in a museum to be named after him. But Anya said the family has yet to discuss how to best preserve her father’s works.

Mansalay Vice Mayor Lynette, 25, Sagangsang’s wife, related how Bapa, whom they call Mama, taught her to appreciate a simple life that values respect. “I thought, with the commitment of Postma to the Mangyans, the more Mindoreños should have that kind of heart for the Mangyan,” she said.