Change has come to Mindoro

It was raining sheets at the Iglit-Baco National Park as we hunkered down inside a thatched hut with three ancient Fufu-amas, elders of the Taw’Buid tribe from Mindoro province. Clad in loincloth, they were smoking a mysterious herb supposed to be tobacco, that smelled like something else.

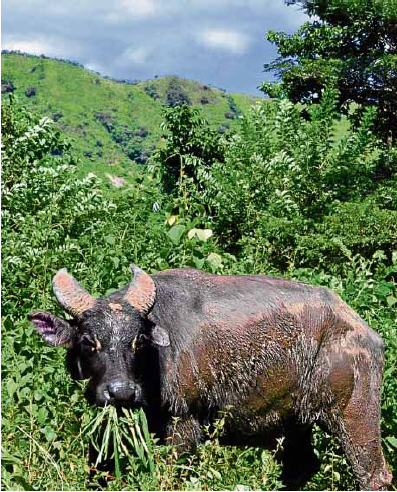

I was last here in 2012 to photograph the endangered tamaraw (Mindoro dwarf buffalo) that several environmental groups are working to conserve. We’ve returned to understand the plight of this indigenous tribe sharing the land with the tamaraw.

Solar lamps

We, from the National Geographic Channel (NGC), Tamaraw Conservation Program and World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), had just given the tribe some solar lamps that we hoped would warm ties and allow us outsiders to visit one of their distant forest villages and see how else we could help.

Close to 20,000 inhabit Mindoro’s central highlands, making the Taw’Buid (“people from above”), the largest of eight tribes here collectively called Mangyan by lowlanders. Once occupying Mindoro’s lowlands, they were pushed into the mountains by Spanish colonizers and Filipino migrants. Peaceful, secretive and deeply animistic, they are careful not to rouse the anger of their gods.

Article continues after this advertisement“We cannot allow just anyone to visit,” said old Fuldo Gonzales. Aside from the threat of disease from the lowlands, his people have reason to fear outsiders. In April, communist rebels attacked a government construction site building a road to Barangay Poypoy.

Article continues after this advertisementRevolutionary tax

The gutted hulk of a backhoe and grader bore testament to the price of refusing to pay the rebels’ revolutionary tax.

Contact with the Taw’Buid was established through missionary groups and the Tamaraw Conservation Program that employs tribesmen as trackers and forest rangers to protect the tamaraw that resembles the more familiar carabao but is found only in Mindoro. About 10,000 thrived a century ago until a combination of cattle-killing rinderpest and poaching left less than 100 survivors by 1969, prompting the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to classify them as critically endangered, just a step away from extinction.

Tams-2

To support existing conservation drives, WWF partnered with Far Eastern University (whose icon happens to be a tamaraw), NGC, Banco de Oro, Primer Group of Companies, Hubbs Seaworld Research Institute and the Taw’Buid people for a project called “Tams-2” or “Tamaraw Times Two,” which aims to double the number of the tamaraw from 300 to 600 by 2020.

“Tams-2” has seen the number of tamaraw in the Iglit-Baco range rise from 327 in 2012 to 413 in April, the highest number ever recorded. “We’ll always protect the tamaraw,” said Taw’Buid chief Fausto Novelozo.“If the tamaraw ceases to exist, our people might well disappear.”

Four national laws protect the tamaraw from poaching, with Presidential Proclamation No. 273 declaring the animal a source of national heritage and pride. Tamaraw Month is celebrated every October in the Philippines.

As we trudged down a muddy trail from Mt. McGowen (also called Magawang), we saw over a dozen tamaraw in the swaying scrub. We also saw Fuldo looking troubled. The tribe had refused us a visit to their forest village, he said, citing how the gods were once angered when outsiders were allowed in, and one of their Fufu-amas died. “Though we need medicine and supplies, we cannot risk angering the gods of the Taw’Buid,” the old man explained.

We heeded their request, gave them our extra supplies and pushed on to another Taw’Buid village where outsiders are allowed, but where the rebels had struck.

As we sat and socialized with the community, I noticed some of the younger Taw’Buid fussing over cell phones. At the turnover ceremony, tribal chief Fausto had expressed reservations about them. “They are creating wants for our people, who now want to cut more trees and grow more rice so they can own one. We have always lived fine without them. To preserve who we are, we must return to the old ways.”

Like at least 5,000 indigenous cultures worldwide, the Taw’Buid are at a crossroads.

The Old Guard like Fausto, Fuldo and the ancient Fufu-amas might hold back the tide, but the younger ones, who have traded loincloth for T-shirts and basketball shorts and are tinkering with cell phones, are starting to embrace the future on their own terms.

At dusk, we said goodbye and left the village, knowing that with time, the forest trails would become paved roads, rivers irrigation canals and the Taw’Buid ordinary folk walking home from the fields.