Special Report on Storm ‘Ondoy’: Marikina remembers ‘end of the world’

MARIKINA residents often describe the day Tropical Storm “Ondoy” (international name: “Ketsana”) battered their city seven years ago, as if it were “the end of the world.”

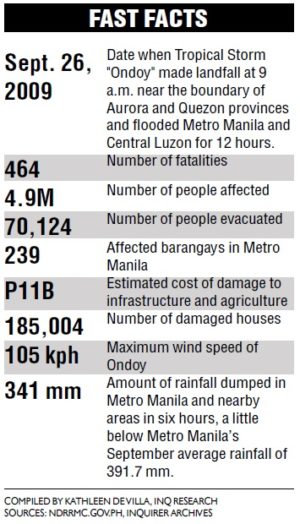

Understandably so because their city suffered the most devastation when the storm dumped on the capital and nearby provinces the equivalent of a month’s rainfall so much so that the Marikina River rose to 23 meters above sea level, inundating 14 of the city’s 16 barangays.

Given the tragedy that struck them on Sept. 26, 2009, Marikeños have chosen to see past the ordeal they went through, learn from its lessons and adapt to the “new normal.”

One of those who survived Ondoy is Bunny Pascual, a resident of Provident Village that was among the severely devastated areas.

Pascual, his wife Nenita and son John still live in their two-story house on Stanford Street, which, at the height of Ondoy, was virtually a river.

Unlike a number of their neighbors who fled and never came back in the aftermath of the storm, the Pascuals chose to stay, primarily because they had nowhere else to go.

Article continues after this advertisement“If we only had [money], we would also buy [a property] in another area because this is really a low-lying area,” said Pascual, a retired seaman who was able to rescue seven of his neighbors, mostly elderly women, who were trapped inside their houses at the height of the storm.

Article continues after this advertisementHe said the floodwaters in his house, which almost reached the base of the chandelier, made him think that it was “the end of the world.”

Canned goods

Pascual’s family and neighbors, who sought refuge in the Pascual house, were able to go down three days, surviving on canned goods.

In the early 1990s, Pascual and his wife knew that Provident Village was prone to flooding, but they still went on to purchase the property because the relatively low price fit their budget.

At the time, he was comforted by the fact that flood mitigation measures were being put in place, including an efficient drainage system.

As an added measure, Pascual built his house several meters above the roadside to ensure that should the area become flooded, his family would not be as affected as their neighbors.

True enough, over the years, he was proven right, since the worst flood his family had experienced before Ondoy reached only the second step of the stairs leading to the front door.

Most prepared

Compared with other cities in Metro Manila, Marikina then could be considered the most equipped and prepared local government unit in dealing with flooding.

Jenny Fernando, head of the local disaster risk reduction and management office, said that before Ondoy, the city believed it had finally found the solution to flooding, especially with the various programs and mechanisms it put in place.

Among these were the squatter-free program, which relocated 7,500 families living along the riverbank to Barangays Tumana, Malanday and Nangka; the 96-meter easement set up along the river; and the construction of various drainage systems and canals.

But the three barangays earlier identified as high-elevation areas would turn out to be among the worst hit as the river grew shallower through the years.

Looking back, Fernando said government interventions put in place would not have made much of a difference because of the heavy volume of rain dumped by Ondoy.

‘New normal’

“The end will be the same because Ondoy was the first worst event that we now call our new normal. We planned to prevent flooding long ago, but not of this kind. It was more than what we had planned for,” he said.

Had the Parañaque Spillway already been built at the time, it could have helped reduce Ondoy’s impact, he said.

Proposed in the 1970s, the Parañaque Spillway was envisioned to drain water from the Marikina River to Laguna de Bay and out to Manila Bay. The project was to be built alongside the existing Napindan Hydraulic Control Structure and the Manggahan Floodway.

Though the project was not realized, the Laguna Lake Development Authority in 2012 said it was looking into modifying it into an underground spillway since the earlier proposed site was already densely populated.

Learning to adapt

Whenever heavy rains pummeled the city, Pascual hoped that the flood these spawned may not be as bad as what Ondoy had brought. Resiliency and adaptation appeared to be Pascual and his family’s refuge, pointing out that they learned to prepare to move to the second floor whenever floodwaters rose.

He now pays close attention to weather advisories and warnings whenever a storm is coming.

Councilors Jun Lazaro and Alan de la Paz of Barangay Jesus de la Peña said that through the years, their community had ensured that residents were taught disaster preparedness.

The local government now knows better as it has learned “not to control the flood but to adapt to it,” Fernando said.

“We tried to control flooding with good drainage systems and the like, but that’s not [the way]. We should adapt. [Because of climate change,] the system has become nonstructural,” he said.