Writers, journalists as freedom heroes

THE PEN is mightier than the sword.

Jose Rizal’s “Noli Me Tangere” and “El Filibusterismo” exposed the ills of Philippine society and the inequities of Spanish colonial rule, inspiring Andres Bonifacio and others to launch the Philippine Revolution in 1896.

During the dark days of martial law when the media were repressed and suppressed, Filipino writers and journalists once again took the cudgels for freedom to become modern-day Jose Rizals.

Soon after President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on Sept. 21, 1972, he closed down newspapers and TV and radio stations. Mass arrests of journalists followed, and only newspapers, which were mouthpieces of the regime, were allowed to open.

But not all journalists were silenced. Among those who were not cowed are now honored as fallen heroes in Bantayog ng mga Bayani.

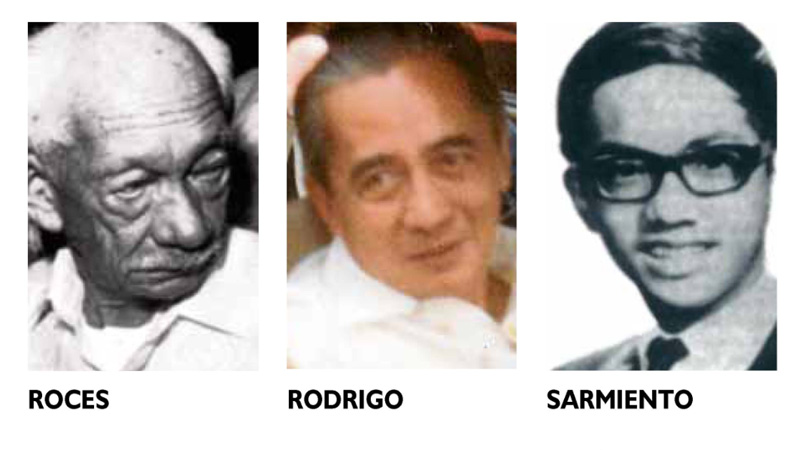

Article continues after this advertisementThey are campus journalists Abraham “Ditto” P. Sarmiento Jr., Ester Resabal-Kintanar and Jacinto “Jack” Peña, publishers Joaquin Roces and Jacobo Amatong, and print and broadcast journalists Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo, Estelita Juco and Alexander Orcullo.

Article continues after this advertisementDitto Sarmiento

“Kung ‘di tayo kikibo, sino ang kikibo? Kung ‘di tayo kikilos, sino ang kikilos? Kung hindi ngayon, kailan pa? (If we don’t speak out, who’s going to speak out? If we don’t act, who will act? If not now, when?) was the challenge issued by Sarmiento, editor of the Philippine Collegian, the student paper of the University of the Philippines.

The challenge was first printed as the banner of a special issue of the Collegian on Jan. 12, 1976. With a collective editorial, “Uphold Press Freedom,” the issue was circulated on the UP campus when Marcos, accompanied by his wife Imelda and top government officials were special guests at the 65th anniversary of the UP College of Law.

Less than two weeks later, Sarmiento was arrested for “rumormongering and printing and circulation of leaflets and propaganda materials.”

He was jailed for seven months, two of which were in isolation under harsh conditions. He had frequent asthma attacks but was denied medical attention. He died more than a year after his release.

Teray Resabal-Kintanar

Ester “Teray” Resabal-Kintanar was editor in chief of Varsitarian, the Mindanao State University (MSU) student paper. She finished a degree in english, cum laude, and got a journalism award upon graduation.

She was a faculty member of MSU-Iiligan Institute of Technology for 10 years before she took an indefinite leave of absence due to security pressures brought about by martial law. Later, she became editor of Mindanaw, an underground protest publication, that kept many communities in Mindanao informed about the realities of martial law.

She was on board the MV Cassandra when it sank in November 1983. Her body was never found.

Jack Peña

Jacinto “Jack” Dechavez Peña completed his AB Journalism course from UP Diliman in 1975, with his thesis, titled “A Content Analysis of Broadcasts of Iloilo City Radio Stations,” which was dedicated to “those whose voices are not heard.”

Peña wrote daily critiques of Marcos policies in underground newspapers. He was one of the editors of Balita ng Malayang Pilipino and Liberation, and helped train news correspondents, reporters and writers for the underground propaganda network.

Peña was wounded, captured and tortured to death by soldiers fighting New People’s Army guerrillas in Gattaran, Cagayan province. He died on Nov. 11, 1979, at age 30.

Joaquin ‘Chino’ Roces

Roces was publisher of Manila Times, the biggest newspaper closed down by Marcos. The dictator ordered Roces arrested and detained multiple times. He brought the fight for press freedom to the streets, defying antiriot policemen who used water cannons, truncheons and tear gas.

Roces led the movement to collect 1 million signatures to convince Corazon Aquino to run for President against Marcos in the 1986 snap elections.

He then revived The Manila Chronicle after Marcos’ ouster. On Sept. 30, 1988, he died of cancer.

What was once Mendiola Bridge in Manila has been renamed after him, where a monument in his honor stands. The street in Makati where the

Inquirer’s main office is located has also been renamed after him.

Jacobo Amatong

Amatong’s Mindanao Observer published articles critical of the Marcos regime. The paper exposed military involvement in illegal gambling and extortion, and reported cases of summary executions and military bombings of communities. It also carried appeals on behalf of political detainees.

He was ambushed by military men in September 1984, on the eve of what was supposed to be a fact-finding mission to document reports of military abuses in Zamboanga del Norte province.

Francisco ‘Soc’ Rodrigo

Rodrigo, a former senator, wrote political commentaries in the alternative press (We Forum and Malaya) during martial law and was imprisoned thrice throughout the regime.

His commentaries, which were in Filipino, centered on the themes of nationalism, protest and reform.

In 1982, he was among the journalists detained for publishing stories that questioned the authenticity of Marcos’ war medals.

As chair of the opposition’s National Unification Committee, Rodrigo helped build unity during the 1986 snap presidential election. He was also a member of the 1987 Constitutional Commission. He died of natural causes in 1998.

Estelita Juco

At 14, Juco lost an arm and damaged an eye in the last days of World War II, when she and her family were caught in the middle of intensified bombing and fighting between American and Japanese troops.

Despite this, she lived a life of courage and hope. She became a well-known student leader in the 1950s and taught at St. Paul College for more than 30 years.

During the Marcos regime, Juco joined the opposition and challenged the conjugal dictatorship of the Marcos couple by writing bold columns and articles. Her house was burned down one night and she suspected that it had something to do with a critical column she wrote about Imelda.

At the post-dictatorship Congress, she was appointed sectoral representative for women and persons with disabilities, a post she held until her death on July 12, 1989.

Alexander ‘Alex’ Orcullo

Orcullo founded Mindaweek, edited Mindanao Currents, and wrote for San Pedro Express in Davao City. He also worked as a radio commentator, denouncing repression and tyranny.

He chaired Lihuk Mindanao and Hukom Demokrasya ng Liga ng Ekonomistang Aktibo sa Dabaw, and served as secretary general of the Coalition for Restoration of Democracy in Mindanao and as political officer of the Makabayang Alyansa.

On his 38th birthday, Orcullo was shot dead from behind by Armalite-wielding uniformed men. Compiled by Almi Atienza, Ana Roa, Kathleen De Villa, Rafael Antonio, Kate Pedroso, and Miner Generalao, Inquirer Research/ ac