BEIJING — In halting televised confessions and emotional courtroom testimony, Chinese lawyers and activists held in a government crackdown have voiced the same ominous message: Shadowy foreign forces are funding, directing and encouraging activities bent on destabilizing China’s government and smearing its reputation.

The familiar narrative of a country besieged by foreign enemies — with the United States implied as ringleader — is a key element of China’s yearlong campaign to stamp out the country’s burgeoning legal activism movement. That effort drew new attention this week with the carefully scripted trials of a lawyer and three activists on subversion charges.

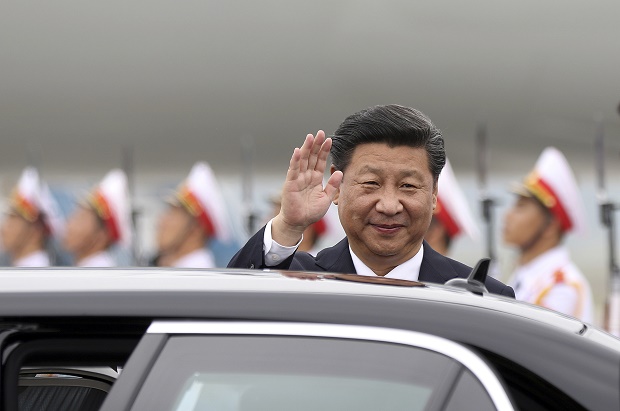

Though the tactic is far from new, political observers say the trials are a reminder of how the administration of President Xi Jinping has wielded the specter of foreign threats with far greater frequency and force, a reflection of the leadership’s deeply seated belief that China is locked in a pitched, strategic and ideological battle against the West.

The four facing trial this week were associated with the Fengrui Law Firm in Beijing, one of the country’s best-known advocates for human rights. Its director, Zhou Shifeng, was sentenced Thursday to seven years in prison while two received suspended sentences and one a term of seven years, three months. All were accused of organizing protests outside courthouses, hyping cases via social and foreign media, and receiving training and funding from foreign nonprofit organizations.

Even if Fengrui’s activist tactics crossed ethical or even legal lines, as some Chinese legal professionals believe, the government had scant evidence to level subversion charges, said Tong Zhiwei, a professor at East China University of Political Science and Law in Shanghai. Rather, the involvement of foreign actors served as the legal and political fulcrum in the cases, Tong said.

“If there were no foreign elements, it would have completely changed the complexion of the cases,” Tong said, pointing out that while the prosecutors pointed to conversations the defendants had in a restaurant about ending Communist Party rule, they offered little evidence of an actual plot to topple the government.

“China has had legal education exchanges for decades with the West,” Tong said. “Where do you draw the line of unacceptable interaction? Is being a visiting scholar at Harvard considered subversive?”

The crackdown on the legal profession, launched in July 2015 with a sweeping roundup of close to 300 activists and lawyers, is part of a far-reaching effort to stamp out suspected foreign influence since Xi took power in 2012. Most have been released although more than a dozen remain in detention.

Also in 2012, the Communist Party issued an internal communique, known as Document No. 9, aimed at limiting the penetration of Western-style “universal values,” such as multi-party democracy and media freedoms, into Chinese society, especially its classrooms.

The government followed that up this year by passing a law to strictly regulate the work of thousands of international nonprofits working in China and place them under direct police supervision. In January, China detained and interrogated Peter Dahlin, a Swedish activist who had provided Fengrui lawyers training and support, for 23 days before releasing and deporting him — but only after he gave a confessional interview with the state broadcaster.

READ: UN’s Ban tells China civil society, free media are crucial

The government’s message was vividly reinforced in statements from those similarly accused this week. In her televised interview, Wang Yu, a Fengrui lawyer, said she intended to refuse all international recognition, referring to an award from the American Bar Association and other Western groups she had received while in jail. “I am a Chinese,” she said. “I can only accept awards from the Chinese government.”

Four years into Xi’s administration, the trials reflect how the party is leaning on nationalism as a pillar of legitimacy at a time of faltering economic growth, said Willy Lam, a history professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“Xi genuinely thinks China is in an existential crisis, and unless the administration can stamp out Western influence, the party may collapse,” Lam said. “But there is also the angle of political expediency. A sizeable part of the Chinese public is very nationalist. If they change the narrative to ‘human rights lawyers are stirring up trouble because the U.S. is behind them,’ they get away from the lawyers’ work on the lack of justice in Chinese society.”

The cases sent party organs and state media into overdrive this week. The Communist Youth League and Supreme People’s Procuratorate, equivalent to the attorney general, circulated on social media an ultra-nationalist video warning of an imminent U.S.-led revolution in China, garnering hundreds of millions of views.

The video’s creator, a Chinese Middle Eastern studies student in Australia, told state media he was motivated to make the video after he perceived in the Fengrui cases the classic warning signs of “the early pre-penetration stages of a color revolution” underway in China, a reference to movements that have toppled authoritarian governments in Georgia, Ukraine and the Middle East.

Jerome A. Cohen, a Chinese law expert at New York University, pointed out that in Wang’s supposed confession, the Fengrui lawyer said she would not “accept, recognize or acknowledge” international awards — the same language used by the Foreign Ministry in rejecting a June verdict by a Hague-based international tribunal against China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea. That verdict prompted Chinese state media to denounce the arbitration process as an American-led ploy to deny China its historical territory.

“Increasingly, law is at the core of both the domestic and international challenges,” said Cohen, who has previously consulted for provincial officials. “Xi is ill-equipped to deal with foreign legal claims, whether they concern international human rights, the law of the sea or economics, but he can slap down domestic purveyors of the rule of law.”

READ: China rejects ruling on South China Sea as ‘null and void’

The unmistakable message has been that, even as Chinese business and society integrates with the world, a hard line has been drawn between Chinese and foreign civil society groups.

“Chinese citizens who have formed relationships with foreign entities are the ones suffering,” said John Kamm, director of the Duihua Foundation, a San Francisco-based nonprofit humanitarian organization. “That’s the main point: Don’t imagine for a moment that a foreign government or entity can save you.”

RELATED STORIES

The West’s decline would hurt China

ASEAN rift raising risk of conflict in South China Sea – experts