Shooting Duterte

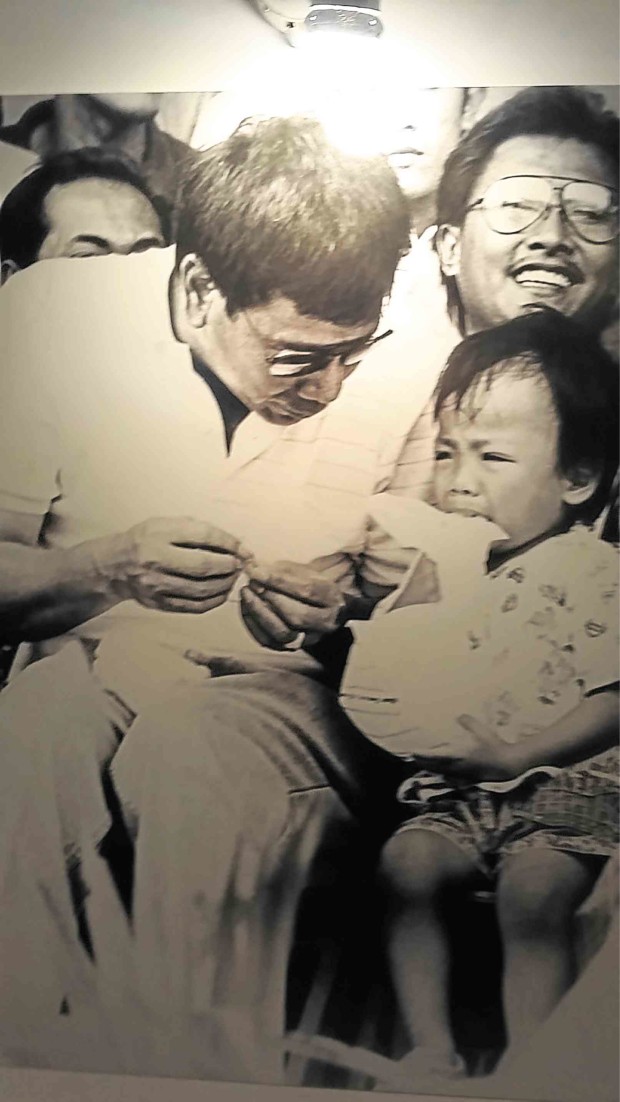

ELIZABETH Zimmerman, former wife of incoming President Rodrigo Duterte, chats with photojournalist Rene Lumawag at the opening of Lumawag’s photo exhibit on his coverage of Duterte for 30 years. Among the photos on display is this one showing Duterte getting the blessing of his late mother, Soledad Roa Duterte, one of the leaders of the anti-Marcos movement in Davao City. ACE MORANDANTE/CONTRIBUTOR

RENE Lumawag still remembers his first glimpse in 1985 of Rodrigo “Rody” Duterte, the young government prosecutor, parking a light blue Volkswagen Beetle by the roadside, watching the march of the Yellow Friday Movement in Davao City before President Corazon Aquino came to power.

At the exhibit, “Rody Duterte, through the years,” photojournalist Lumawag unveiled a series of photographs showing how that young prosecutor evolved from being a new politician starting out as the vice mayor of Davao City to the brazen candidate who would be the 16th President of the Philippines.

“Here, we’re going to look at the man who has become a household name,” Lumawag said as his two-week exhibit opened at Abreeza Mall on Thursday.

Featured on a display panel is a photograph of a younger Duterte, his lean, bespectacled face flashing that sharp, street-smart look that has been his signature as Davao City’s tough-talking mayor through the years.

In Zimmerman’s eyes

Duterte’s former wife, Elizabeth Zimmerman, described him as a “thoughtful person,” and how she never doubted he was someone who could do “great things for the country.” She also described Lumawag as someone who had always been there, documenting the life of the city and the man at the center of it, in the last 30 years.

Zimmerman recalled a country-wide motorcycle tour with Lumawag, when they passed by the San Juanico Bridge in Leyte, and numerous occasions with Lumawag and the Duterte family.

Lumawag described his subject as a simple man, tough and yet soft-hearted.

One of the earliest photographs showed Duterte, his face haggard and tired, a white handkerchief tied around his head. Wearing a black jacket, he was squatting on the floor inside a hut with former Davao City Mayor Zafiro Respicio, while talking with “lumad” leaders in the hinterlands of Davao.

They were trying to settle a “pangayao,” a tribal retribution system that often turned bloody in this part of the country.

“It’s simply being at the right place at the right time,” said Lumawag of the moments he was able to capture Duterte in pictures.

In another panel, Digong is shown playing checkers with a child at the Osmeña Park while other children watched.

ELIZABETH Zimmerman, former wife of Duterte, signs the guest book at the photo exhibit of Rene Lumawag. ACE MORANDANTE/CONTRIBUTOR

Capturing the image

“Here’s the difference between stills and video,” Lumawag explained.

“In video, you see a fleeting image. The image simply moves, passes before your eyes so swiftly, before you can even hold on to it,” he said.

“But in stills, you can hold the image in your hand,” he added, pointing at a canvas showing the younger Duterte bowing before his late mother, Nanay Soleng, as he kissed her hand.

“You could not capture this on video,” he said of the frozen image of Digong bowing before his late mother, once the leader of the Yellow Friday Movement in Davao that helped oust a dictator and propelled Aquino to power.

Zimmerman said kissing the hands, rather than the fashionable beso-beso, had been a habit so entrenched among the Duterte children and grandchildren to show respect and love for their elders.

Lumawag was born in Panay on Dec. 22, 1944. As a young man, he painted big cinema murals in Zamboanga City, advertising what movie was showing for the week, before a tragic landslide years later in Davao opened the door to photojournalism.

When he arrived in Davao City, Lumawag dabbled in broadcasting, as a radio deejay, and went on to work as an advertising painter and sign artist for roads and highways. He worked at the municipal treasurer’s office in Digos, Davao del Sur, too.

He bought his first Minolta 100x camera in 1979, merely to record the growing up years of his children. But in the summer of 1985, a tragic landslide happened, burying hundreds of miners in Diwalwal.

The renowned Reuters photojournalist, the late Willie Vicoy, asked Lumawag to cover the disaster. His photographs, which landed on the front pages of major newspapers, opened the door to the Davao tabloid San Pedro Express, and later, the Ang Peryodiko Dabaw (which eventually became Sunstar Davao).

It was during his work in the tabloids that Lumawag’s and Duterte’s paths crossed.

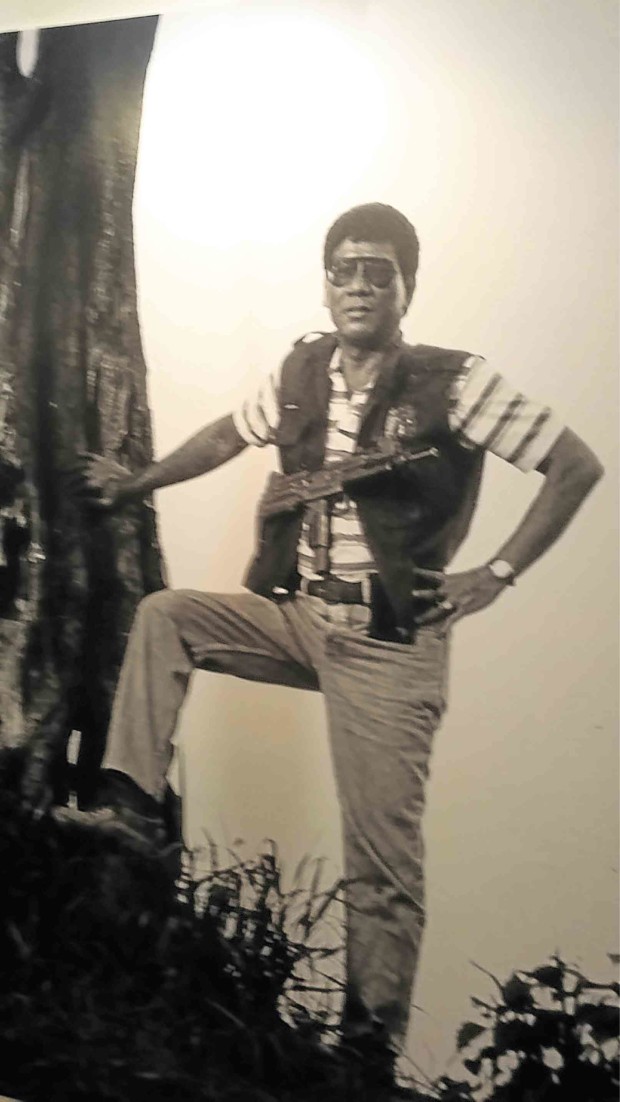

A PORTRAIT of Duterte, with a submachine gun slung on his shoulder, is one of the earliest photographs taken of the incoming President by photojournalist Rene Lumawag. RENE LUMAWAG

Lumawag used to work, too, as photo correspondent for the Philippine Daily Inquirer in the 1990s.

In another photo panel, captioned “Ground Zero,” Duterte, with rolled up sleeves, checks the assault rifle of then Senior Insp. Ronald dela Rosa, the chief of the city police mobile group, after inspecting a crime scene in Barangay Tamugan.

In the picture, the young Dela Rosa, recently named by Duterte as head of the Philippine National Police, is shown watching Duterte examine his assault rifle, along with then city police chief Isidro Lapeña, recently named Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency head.

ONE OF the earliest pictures taken of Duterte by Lumawag is this one showing the then first term mayor looking after a boy, Toperjay Pore Quijano, now a grown man, who got lost in Rizal Park in Davao City and was noticed by Duterte. RENE LUMAWAG

Dangerous times

Lumawag, who has since retired from Sunstar Davao and is now a lifestyle photo contributor and photo consultant for Mindanao Times, considered the hostage-taking, led by Felipe Pugoy, among his most dangerous assignments in covering Duterte. Duterte, a young mayor then, convinced the hostage-takers to free their prisoners in exchange for him, as their hostage.

“It took too long for the hostage-takers to decide,” Lumawag said.

“A police officer asked the mayor, ‘Rody, are we doing the right thing here?’”

The rest is history. The hostage-takers were subdued, and a joke uttered about one of the 27 victims later drew flak at the height of the presidential campaign period.

But the man behind it all is now the 16th President, someone who Lumawag had shot and would continue to shoot.