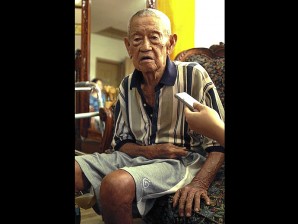

DIONISIO Batalla Valbuena could only sympathize with the younger generation of weather forecasters in the predicament they figure in every year as the public’s whipping boys for “erratic” typhoon advisories.

As early as some seven decades ago, people pinned the blame on him whenever a raging storm ravaged town without warning from him, recalled Dionisio, perhaps a living testament to the blame game that ensues between residents and government officials after storms pass.

A weather observer by profession, Dionisio turned 100 on May 8 when Tropical Storm “Bebeng” (international codename Aere) surprised Metro Manila with a heavy downpour and flooding in some areas.

Forecasters at the Philippine Atmospheric Geophysical and Astronomical Service Administration (Pagasa), as expected, had an earful from irate residents.

“Some don’t mind the forecast, some even dismiss it as fake, but when it comes, it’s there. Then you blame the weather bureau?” Dionisio lamented in an interview with the Inquirer.

With a firm grip on his walker, Dionisio stands with a stoop and has poor hearing, but the memory of his three-decade career at the defunct Weather Bureau starting in 1937 was as vivid as the clear blue sky on Wednesday morning.

He lives with his daughter Zenaida Valbuena-Espino and her family at their Las Piñas bungalow since being widowed in December last year.

Both Dionisio and his wife Engracia stayed with their daughter when they returned to the country in 2001 from the US where the veteran weatherman settled after his retirement from government service in 1973.

In his raspy voice, Dionisio replies with detailed answers from questions he reads on sheets of paper that his daughter writes on. Zenaida said she resorted to this mode of communication since his hearing deteriorated.

By Dionisio’s answers to queries pertaining on his work for the then Jesuit-run observatory, weathermen in his day earned the ire of the public whenever forecasts wouldn’t match with the actual weather.

Abrupt weather changes

“It may happen,” noted Dionisio referring to abrupt changes in direction of storms, “because who knows exactly what is going on? The weather may change anytime. You say it goes to northern Luzon the morning, but it veers in another way.”

Zenaida recalled an instance when townsfolk of Cabanatuan was angry at his father for allegedly not informing them that a typhoon was to pass through their area. “But he managed to issue a notice of the impending weather disturbance.”

For Dionisio, two problems compounded his work at the weather station in Cabanatuan, where he worked for 16 years—he was a one-man office at the observation post, and he got no help from the local government there.

“You must have a calesa or truck to go around there to tell about the coming typhoon, but that does not happen. Some municipal and provincial officials are not so cooperative,” he continued.

“They just laugh at it, and say ‘Is that so? May bagyo na naman? (There’s another storm?)’ But the moment it comes, they blame you,” said Dionisio with a chuckle.

Besides, he couldn’t leave his post because no one would tend the area when he was away. People might also think he abandoned his station and report this to his higher-ups, he said.

Barometer and wind vanes

To gauge the weather then, all he used were the barometer and wind vanes, among other instruments, and cross-reference values with historical charts to come up with forecasts, he said.

Dionisio hailed from Baybayog, Cagayan, where he left in 1931, on a whim upon prodding of a friend to go to Manila. When he told his mother he wanted to go to the capital, she told her son the family had no money.

The following day was the town’s market day, and Dionisio asked his mother if he could go to Manila. In turn, his mother sold “some of our animals” to raise money for his fare.

In Manila, Dionisio and his friend worked in Ateneo de Manila as a waiter and porter respectively. Eventually, they found their way to the Weather Bureau, headed then by Spaniard Fr. Miguel Selga, SJ, where they studied.

He finished the course on weather observation in 1937, then took the civil service examination. He passed and got assigned in Cabanatuan City where he spent the first 16 years of his career.

In 1954, he was reassigned to Tuguegarao, where the working conditions were much better, he recalled. There, he had another weatherman to keep watch on the second shift after him.

His next tour of duty was in Aparri where he boarded ships at the port as a duty weatherman to guide navigators out of weather disturbances.

Back to Manila

He moved back to Manila in the 1960s to the weather bureau headquarters in Quezon City and spent the remaining years of active service until his retirement in 1975. He brought Engracia to the US to live with another daughter Baby.

Dionisio recalled that bureau director Jose Kintanar tried to talk him out of retirement, even offering a promotion to egg him to stay one more year.

“All the answer I could give [was] ‘I’ve made up my mind, sir.’ I was 65 at that time,” he said.

Today, Dionisio rarely keeps abreast of the day’s events by reading the newspaper or watching television, though Zenaida said her father used to be a voracious reader.

Since Engracia’s death in December, Dionisio plummeted to depression as he took care of his wife who developed Alzheimer’s in her later years. She died in her sleep at 88.

Her father watched television on his birthday viewing the lopsided Manny Pacquiao fight against Shane Mosley.

Though his physical activities are now limited by age, Dionisio still shows off the weatherman in him. “We’re very lucky this year, because by the looks of it, no strong typhoon might be coming over,” he said.