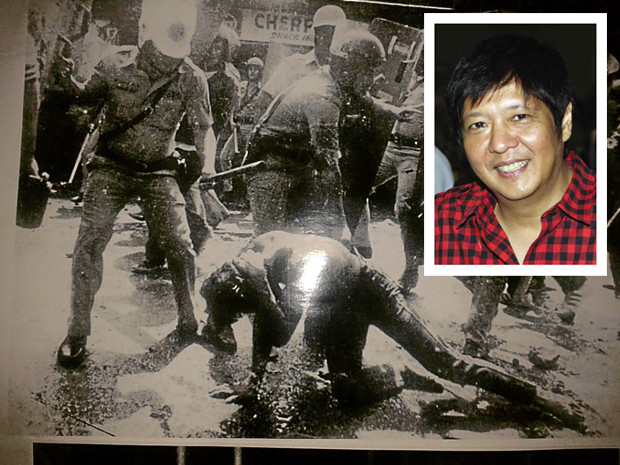

Vice presidential aspirant Bongbong Marcos (inset) conceded in an interview that there were human rights abuses during the time of his father’s dictatorship. He insisted that human rights abuses also occurred during succeeding administrations. INQUIRER FILES

On the verge of securing his family’s biggest victory since their humiliating downfall three decades ago, the son of dictator Ferdinand Marcos talks confidently about his political ambitions and his father’s legacy.

In an exclusive interview with AFP ahead of May 9 elections, with surveys showing he could win the vice presidency, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. conceded there were “widespread human rights abuses” during his father’s rule.

READ: PCGG: Bongbong blocked return of $40M to gov’t | Robredo: Bongbong Marcos’s lack of remorse is worrisome

But the 58-year-old insisted the Marcos name remained one of his strongest assets, as he stuck to a no-apology mantra that has been a key part of his family’s remarkable political resurrection.

“I think one of the things that is happening now is I am a beneficiary of the good work that was done in my father’s time,” Marcos said on Monday night at his campaign headquarters in the Philippine capital.

“There were so many different things that were initiated at that time that to this day are of benefit to the people.”

Marcos was a fresh-faced provincial governor in his father’s dictatorship when millions took to the streets in a famous 1986 “People Power” uprising that forced the family to give up two decades of power and flee into US exile.

The Marcos family and its business allies are accused of plundering billions of dollars during the patriarch’s rule, while the regime’s security forces allegedly killed and tortured thousands of critics.

However, after Marcos Sr. died in exile in Hawaii in 1989, his controversial wife, Imelda, and their children were allowed to return to the Philippines, and they slowly began rebuilding a power base.

‘Golden age’ debate

Part of their strategy was to portray the Marcos years as a golden age of peace, security and infrastructure-building for the nation.

They also consistently denied any major wrongdoing, fending off dozens of legal challenges and probes aimed at retrieving the fortune allegedly stolen from state coffers.

Marcos, who rarely gives interviews, deflected questions about mass theft by his parents, saying he believed accusations against them were exaggerated but that he was not privy to their decisions.

“I think a great deal of it was made up because none of it has been verified,” he told AFP when asked whether they stole billions.

“These huge numbers that we hear about, we don’t really know where they come from and how they were made up.”

Marcos did concede there were abuses under his father’s regime, but insisted they were no worse than those committed by the democratically elected governments that followed.

“I acknowledge that there were,” Marcos said when asked about human rights abuses under his father’s rule.

“(But) there are widespread human rights abuses in any administration and that is a problem that we as a country have to face.”

Memories of the Marcos years have dominated this election campaign.

In the Philippines, the president and vice president are elected separately.

Marcos’s bid for the vice presidency has stolen many headlines away from the race for the top post — which in itself is a fascinating four-way tussle.

President Benigno Aquino, whose mother led the “People Power” revolution and succeeded Marcos as president, has repeatedly urged Filipinos in recent months to never forget the dictatorship’s horrors and stamp out the Marcos comeback.

Presidential plans?

However Marcos — who has enjoyed a high national profile as a senator since 2010 — is in the lead or running a close second in the race for the vice presidency, according to various surveys.

His controversial mother, Imelda, 86, is also regarded as a near certainty to win a third term as a congresswoman representing the family’s northern provincial stronghold of Ilocos Norte.

And one of his sisters, Imee, will secure a third term as Ilocos Norte governor, with no opponent challenging her, while other relatives are expected to easily secure lower level posts.

One important aspect of the family’s success has been its ability to tap into a vast network of allies that never fully crumbled despite the revolution.

A younger generation of voters fed up with corruption and politics in modern society has also proved receptive to the Marcos “golden age” mantra.

Asked why he wanted to become vice president, the former governor of Ilocos Norte spoke at length about wanting to return to the executive branch of government because that is where he could do the “most good”.

He insisted he was not gunning for vice president as part of a grand plan to run for the presidency at the next elections in 2022.

“That’s not something I am thinking of at all right now. Every brain cell that I have is directed towards this campaign,” he said, when asked about a presidential bid in six years, but then nevertheless spoke candidly about his loftier ambitions.

“Of course you have a political career and many times you’d be frustrated and think: ‘God if I was president I’d fix this in a flash’… and in that sense I guess we all aspire to that.”