The resurrection of Mt. Magdiwata

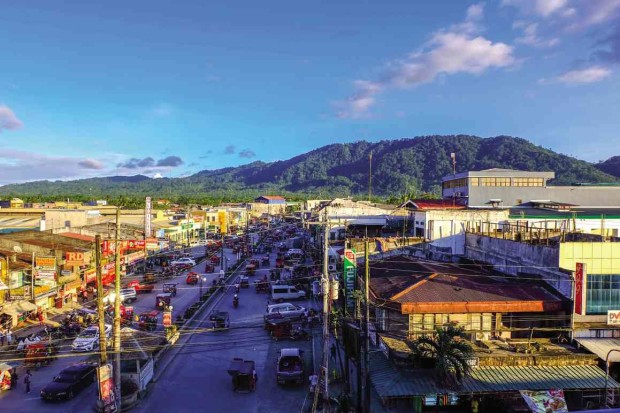

THE MAJESTIC Mount Magdiwata as seen from the town center of San Francisco in Agusan del Sur province CHRIS V. PANGANIBAN

SAN FRANCISCO, Agusan del Sur—RESIDENTS of the booming town of San Francisco in Agusan del Sur province took pride in celebrating World Water Day last week as they enjoyed an abundant supply of water in their homes coming from Mount Magdiwata.

San Francisco Water District (SFWD) said water from the four spring sources inside the 1,658-hectare watershed area was “200 percent” more abundant, noting these could supply the town’s needs in the next four years.

Progress in San Francisco has been so rapid in the last five years that it now hosts three big shopping malls.

There is more than enough supply of water because the Mt. Magdiwata watershed’s forest cover is now 98 percent, after 20 years of a massive sustainable reforestation program initiated by SFWD.

Elmer Luzon, SFWD manager, said these water sources could produce at least 147 liters per second, enough to supply about 12,000 residential, commercial and industrial consumers.

Article continues after this advertisementBanking on Presidential Proclamation No. 282 signed by former President Fidel Ramos in 1993 that declared the area a permanent watershed and forest reserve, SFWD initiated an intensive campaign to protect Mt. Magdiwata against encroachment.

Article continues after this advertisementThe forest used to be denuded, with about 900 ha that had turned into an open area grassland after large-scale logging in the 1960s up to 1970s and the unabated tree-cutting activities in the 1980s to supply lumber-milling plants that proliferated around town.

Dying mountain

The presence of about 200 occupants, mostly living on sloping terrain and some on plateaus where they plant root crops and coconuts, added woes to the dying mountain.

According to SFWD studies, only 695 ha of natural forest (41 percent) was left in the Mt. Magdiwata watershed in December 1997 since around 1,200 ha had been considered inadequate forest, open area grasslands, and small portions of manmade forest, palm oil and abaca farms.

No formal biological research had been done on the mountain’s ecosystem, but a surviving kin of the pioneering Manobo settlers revealed that the flora and fauna had started to flourish again, a scene long gone due to decades of disturbance to its rich biodiversity.

“It’s quite different now because I feel the rainforest drenching us once more—an experience I never had for a long time,” said Silverio “Datu Tuwa-tuwa” Maguinda.

A lot of challenges were faced by SFWD when it initiated the reforestation program, starting with a study on the socioeconomic profile of occupants inside the watershed and a consultative dialogue with all groups involved in reviving the mountain.

SFWD inventoried tree species that still thrive in the forest that served as its baseline data to develop a comprehensive reforestation program in partnership with Livelihood Enhancement through Agroforestry Foundation Inc. (LEAF Foundation).

“Against all odds, we stood our ground,” said a teary-eyed Luzon as he recalled the hardships they faced.

Some residents living within the buffer zone on the foot of the mountain were tapped as “social fence” and were offered livelihood assistance to develop agro-forestry organic farms through the “Imong Yuta Ugmara kay Bayaran Ta” (Toil your land and we’ll pay) program.

Danilo Baton, 62, who has been planting lemongrass in a hectare of land since last year, supplies the public market with an average of 400 bundles a day. Baton’s income from selling lemongrass, at P10 a bundle, helps him send two children to college.

Baton recalled the rampant illegal cutting of trees, mostly prime species like lauan and apitong, in the area that was perpetrated by a police officer and a leader of the dreaded “Lost Command,” or more known as LCs, a paramilitary group.

There was strong resistance when the water district offered settlers, especially in the upland areas, a relocation plan to pave the way for the reforestation program.

Among those vocal against the relocation plan was Remegio Abarquez, now manager of Mountain Spring Multipurpose Cooperative Water System in Bayugan 2 village.

Abarquez, who used to maintain a coconut farm in the sloping upper portion of Magdiwata, however, agreed to relinquish his small lot after he understood the better option of reforesting the area. He is now involved in the replanting of trees and was encouraged to set up a cooperative, which will supply potable water to some 400 households in their village.

Threat

Another threat faced by Magdiwata was small-scale gold mining.

A large crack, with a kilometer in diameter, was also found by forest rangers near the summit in 2014, causing alarm to residents of a possible landslide that may bury an outlying village when heavy rains occur.

Amid the threats to Mt. Magdiwata, the water sources tapped by SFWD continue to serve the town, even as the town’s population was projected to increase rapidly in the last five years.

Three more surface water sources were built last year from the P130-million loan funded by the Development Bank of the Philippines to address the increasing demand of residents.

Luzon expressed confidence that San Francisco residents would not experience a water crisis in the future.

“As long as we keep on preserving Mt. Magdiwata … the people will not go thirsty,” Luzon said.