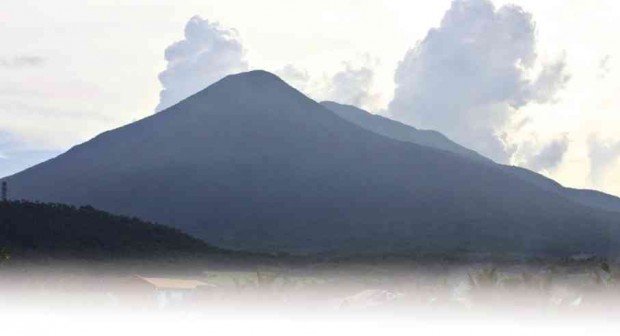

PILGRIMS and trekkers are allowed only in designated areas at the base of Mt. Banahaw in Quezon and Laguna provinces as the government extends the closure of the mountain until 2019. DELFIN T. MALLARI JR.

Pilgrims and mountaineers expecting to spend their Lenten retreat this year in the deep recesses of mystical Mt. Banahaw, which embraces Quezon and Laguna provinces, would be in for a disappointment.

Authorities have again extended the mountain’s closure by three more years, or until February 2019, after scheduling its opening last month.

The decision was reached by the Mounts Banahaw-San Cristobal Protected Landscape-Protected Area Management Board (MBSCPL-PAMB) during a meeting held in Dolores town in Quezon on Feb. 19. The multisectoral body was created by law to keep watch over the government-declared protected areas.

Salud Pangan, Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) park superintendent for Banahaw and adjacent Mt. San Cristobal, said 18 of the 31 board members who attended the meeting supported the proposal to keep people out of the mountain until 2019 while four wanted a shorter ban extension of only a year.

“The rest abstained from voting,” Pangan said. “But we all agreed that we have to protect the gains and continue its remarkable rehabilitation.”

Representatives from all towns at the foot of Banahaw are members of the board.

The 10,901-hectare Banahaw and San Cristobal straddle the towns of Lucban, Tayabas, Sariaya, Candelaria and Dolores in Quezon province; and parts of the towns of Rizal, Nagcarlan, Liliw and Majayjay, and San Pablo City in Laguna province.

Reynulfo Juan, DENR Calabarzon regional executive director and chair of the MBSCPL-PAMB, said: “We will advise local governments [around Banahaw] to focus on disaster preparedness and to strictly regulate activities within strict protection zones.”

“We don’t want to return to the situation during past Lenten seasons that the mountain would turn into a free highway for everyone,” said Randy Matibag, municipal environment and natural resources officer of Dolores.

Reviving the mountain

In 2004, the PAMB installed barbed-wire fences to seal off several trails leading to the bosom of Banahaw to start a program to revive the mountain’s natural resources. Environment personnel have attributed the deteriorating conditions of the mountain to years of abuse by trekkers and pilgrims.

After the closure order was extended several times, Congress passed Republic Act No. 9847 in 2009, which designated Mt. Banahaw and Mt. San Cristobal as protected areas. The law prohibited the entry of visitors until February this year to protect gains in reforestation activities since 2004.

Return of wildlife

Wildlife species, including the rare Rafflesia that is considered the world’s biggest flower, began to reappear in the hills and gullies in 2012. “[You can see] lots of rafflesia along the old mountain trails that are now covered with thick vegetation. If we reopen the mountain, all of these rare and exotic flowers will again [disappear],” Pangan said.

Several animal species, such as wild boars, monkeys and wildcats (musang), have also returned and have been seen roaming near the mountaintop by environment personnel.

Many people believe that Banahaw is inhabited by spirits, elementals and otherworldly beings. They trek its slopes and offer prayers in the hope of miracles, particularly during Lent.

Since the mountain’s closure, the yearly throng of religious pilgrims, mountaineers and nature trippers have been allowed only at selected spots at the base. “We will open more spots at the foot of Banahaw for nature lovers and for the spiritual activities of pilgrims,” Pangan said.

Climbing destination

More than half a million had climbed Banahaw every Holy Week more than a decade ago. Last year, the number was placed at 5,000, up from the 3,000 in 2014, according to tallies of the DENR and the Dolores local government at the guarded entry point leading to Barangay Kinabuhayan.

Matibag said his municipality of Dolores was not yet ready for the reopening of the mountain to the public. It is still reviewing its tourism development plan on Banahaw, he said.

Local officials have wanted to make sure that once Banahaw is reopened, the system for a regulated entry of visitors is in place, he said. This will cover registration, briefing of visitors, employment of trained guides and porters, identification of hazards and safety precautions, and data on the mountain’s carrying capacity.

Tanggol Kalikasan, a public interest law office advocating environmental protection, has supported the continued closure of Banahaw “until such time that the protected area has fully recuperated and regenerated.”

Its regional area director, Glenn Forbes, urged PAMB to conduct regular and science-based monitoring and assessment to measure changes in forest cover, wildlife as well as reduction of threats in the mountain.

“Finally, the new … set of local officials must be made aware of these necessities and the need to collaborate in effective law enforcement in the area,” Forbes said.