US role in Edsa revolt: Retaining control

(First of two parts)

It has been said that history has eyes that only look backward. The present is unreliable, with distorted and inconsistent images; yet to move too far away can allow these images to dissolve altogether.

Given that, 30 years from the Edsa People Power Revolution cannot yet afford the needed distance for a truly objective review. But what we have, at least, is a broader perspective from which to view the past in a better light.

We respect and learn from the past, Juan Enriquez and Steve Gullans say in their groundbreaking 2015 book, “Evolving Ourselves,” but (we should) always focus on building the future.

Looking clearly at the past is essential, and these personal recollections are intended to help along those lines (although viewed through a filter that can be selective, biased and perhaps incomplete).

In the long run, however, the truth will have a way of asserting itself. That is why, when we are not sure what to make of some contentious event, we are wont to take refuge in the phrase, “let history be the judge.”

Article continues after this advertisement

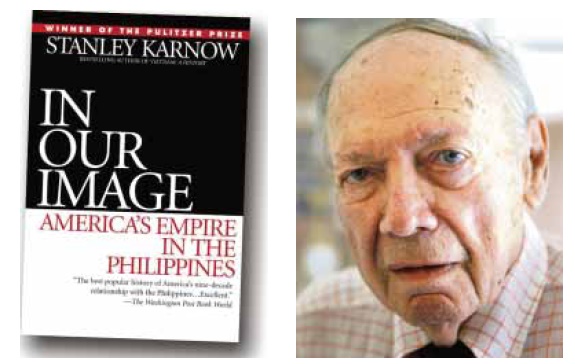

US CHRONICLER American historian and foreign correspondent Stanley Karnow is known to Filipino readers

as the man who wrote “In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines.” The book deals with nine decades of US ties

with the Philippines. AP

US role

Article continues after this advertisementThe role played by the Americans in the Edsa Revolution has been a standing question, underlined by Stanley Karnow’s observations in his book “In Our Image.”

Writing about America’s imperial experience, Karnow has produced a comprehensive and vivid account of how this global power sought to remake the Philippines in its own image, complete with American political, educational and cultural institutions.

Karnow is a painstaking journalist, and has spent many hours in the Philippines to learn as much as he can about Edsa.

The portions in the book where he writes about the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM) was the result of several lengthy meetings with him, including about two hours of videotaped interview, snippets of which found their way into a lengthy documentary that he also produced.

The book includes a brief but broad chronology of events that traces the progress of American influence in our history.

Interestingly, where Karnow recounts the events around Edsa, he altogether omits the military and civilian uprising that paralyzed President Ferdinand Marcos and instead concentrates on US efforts to take Marcos out of the country as the best route to a stable transition.

The impression created, at least in that chronology, was that in spite of the dicey situation, the Americans were constantly on the ball, and that they delivered brilliantly.

As I would write later in an article for a local publication, my own perception was that the Americans were trying to retain control in a situation where the growing influence of the RAM threatened to alter the status quo. I will try to explain with some anecdotes.

Pentagon ‘emissary’

Around mid-1985, at 9 p.m., I opened the door of my Camp Aguinaldo quarters to a tall Caucasian in a plain white shirt and dark pants.

Drying himself from the effects of a downpour, he introduced himself as William “Bill” White, a US Army colonel from the Pentagon’s East Asian and Pacific Affairs office.

He was there to deliver a message from the Pentagon authorities and he straightforwardly proposed a meeting with the RAM leadership.

The RAM organization at that time was amorphous and ill-defined. The original organizers, young officers all, abhorred the limelight.

To this day, none of them wants to be identified, and I myself didn’t know exactly why this Pentagon official sought me out. I may be the RAM spokesperson, but I certainly was not one of its organizers.

At any rate, after checking out White’s credentials, a small representative group of RAM members agreed to meet with the Pentagon “emissary.”

(Military attachés at the US Embassy had identified White as then working for Richard Armitage, the US assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs at the time).

My own objection to the meeting, I told Greg Honasan, was that the Americans were hardly to be trusted as they were on the side of Marcos. We were deep in planning at that time and we didn’t want to give the Americans a hint of what we intended to do.

In any case, a consensus was reached to talk to White. (I recall with amusement Honasan’s reply to my private misgivings: “They will be too smart for us, Greg,” I complained. “Don’t worry, Sir, we can totally outsmart them,” he reassured me.)

The message

Apparently regarding our makeshift group as indeed the RAM leadership, White formally delivered this message: “Refrain from resorting to violence in pursuing your quest for reforms and we will protect you from arrest.”

The Americans quickly consolidated the advantage obtained from this initial contact. Other “friendly moves” followed.

The Pentagon arranged for Jeffrey Race, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his book “War Comes to Long An,” to be sent over to us to lecture for several weekends on the dynamics of power from a historical perspective.

What struck me most was the discussion on the fate of Shi Huang Ti, builder of the Great Wall. Power was so centralized under his rule that when he died, the entire system collapsed. His own brother could not prevent the chaos that ensued after he was gone.

Race spoke Filipino and was wont to read the bilingual tabloids as he thought them more revealing of Filipino culture and interests.

A language coach would call him periodically from the United States to query him on the items in the afternoon tabloids.

A boxful of copies of “On Strategy” written by then US Army Col. Harry G. Summers Jr. arrived after the RAM expressed mild interest in the book. Each copy bore an autographed dedication from the author himself.

A critical analysis of American military strategy, the book extends well beyond the battlefield to the political leadership and the people themselves.

Other books followed such as “The Stones Cry Out,” about the sufferings of an oppressed people

Noticed by Pentagon

How the RAM came to be noticed by the Pentagon may be traced back to February 1985 when, after being assailed for being “cowards hiding behind the cloak of anonymity,” members of the group responded by blatantly presenting themselves at the Philippine Military Academy foundation day parade and carrying streamers proclaiming “We Belong!” to belie the charges against them and to assert that they were standing by the issues they had raised.

On July 4, 1985, the RAM held its first press conference at the National Press Club building in Intramuros, with foreign correspondents, predominantly from American publications, very much in evidence.

One of them, Rodney Tasker, wrote a groundbreaking article, “The Hidden Hand,” for the Far Eastern Economic Review. His assertions regarding the RAM, the state of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the problems of the Marcos regime were a revelation even to some members of the AFP high command.

Marcos sprang a surprise by calling a snap presidential election in late 1985. In response, the RAM launched Kamalayan ’86, a nationwide campaign for clean elections.

The activity also served as a convenient cover for the recruitment of soldiers and civilians alike, for the contemplated military-led move to withdraw support from the presidency.

Reagan’s support

Then US President Ronald Reagan was inclined to support Marcos and, right after the election, in response to accusations that Marcos stole the vote, he issued an equivocal statement (to the consternation of his closest advisers) that cheating could have come from both sides.

Pentagon officials, like many members of his advisory staff, strongly disagreed with Reagan and went further by bringing in a tall, fine-looking woman of mid-European descent, Mary Tai, who was then head of their Philippine desk.

Tai flatly told Reagan that, based on the best intelligence assessment, the RAM would likely move aggressively against Malacañang if he did not issue a retraction.

Pleasant and personable, Tai was allowed to visit the Philippines after Edsa. She endeavored and was able to meet Honasan and other RAM members and shared with them interesting (if unclassified) stories about her work at the Philippine desk.

But to our dismay, she was barred from traveling to the Philippines after that brief visit.

Pentagon officials also had in their possession voice tapes, obtained by the RAM, of instructions to alter election figures in favor of Marcos.

The tapes came from a Palace resident to a ranking computer official at the Philippine International Convention Center, where the returns were being televised.

The damning contents of the tapes must have also helped to persuade Reagan to issue his retraction.

The tapes were radio intercepts by a team under Red Kapunan whose work was simplified since it only had to keep track of the one and only frequency used by the Palace.

In those days, changing frequencies was inconvenient, cumbersome and expensive, and nobody in the Palace group must have thought that a change was advisable.

We discreetly passed copies of the tapes to one of the military attachés who forthwith dispatched them by courier aircraft to Washington.

———————-

Editor’s Note: Rex Robles, a retired commodore in the Philippine Navy, is a former member of the Reform the AFP Movement and served on the Feliciano Commission that looked into the roots of the July 2003 Oakwood mutiny as well as corruption in the military.